|

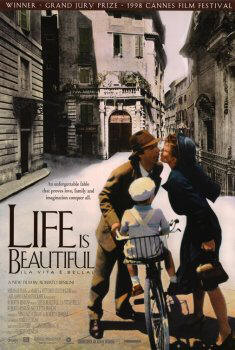

LIFE IS BEAUTIFUL Revisited, Or "God, How I Hated LIFE IS BEAUTIFUL!" By Michael McGonigle

I know Roberto Benigniís tragic/comic Holocaust film is wildly popular with audiences. I know it received numerous Academy Award nominations and won three Oscars including Best Actor and Best Foreign Language Film. And I will agree with critics of mine who point out that part of my hostility toward the film is directly related to the fact that it IS wildly popular.

But I donít care. Furthermore, I do not intend to be fair towards La Vita e bella. In fact, I intend to rip it a new asshole if possible. I am very biased against this film. I hate it. I truly, truly hate it. Thinking about it makes me cringe, watching it makes me feel unclean.

Until recently, my feelings regarding Life Is Beautiful were merely contemptuous, which was my initial reaction after first seeing the film on its original American release back in 1998. But while researching a lecture on Concentration Camps In Movies, I re-watched Life Is Beautiful on DVD and that is when my indifferent disdain transformed into spittle spewing hate.

You see, part of my research included reading a 1989 article by Nobel Peace Prize winning humanitarian and concentration camp survivor Elie Wiesel titled Art And The Holocaust: Trivializing Memory (itís available on-line here) where Wiesel argues that the Holocaust should be off limits as a dramatic subject.

Wiesel believes that the Holocaust was an event of such monumental horror that it is beyond the capacity of artists to create anything meaningful about it and that the very act of reducing any part of the Holocaust to the form of a melodramatic narrative, with a beginning, middle and end is to automatically trivialize it. Itís felt that human art, at best, can only approach very specific aspects of the Holocaust and can in no way present the story with the kind of respect and deference it needs.

This may explain why so many films about concentration camps have accentuated the positive, like the TV movie Escape From Sobibor, which told the specific story about the October 1943 mass escape of prisoners from the Sobibor concentration camp, or even Schindlerís List, which wasnít even about the camps or even the Jews, but about one German manís dealings with the Naziís and how he saved nearly 1100 Jews from extermination. Film producers seem determined to find an uplifting message in the Holocaust.

But is that what the Holocaust was about; life affirming sacrifices, brave escapes and humanitarians saving people? I donít think so.

The justly famous picture taken by an Army Private is one of the most well known images ever taken at a Nazi concentration camp. On the right of the frame stands a bony, bare-chested, young man decorously covering his lower body with the pants portion of his scruffy striped prison uniform. On the left of the picture we see several rows of hard wooden bunk beds with about two-dozen other prisoners looking out from their bunks at the camera. These sad, hollow-eyed men are emaciated and have blank uncomprehending stares. They are too thin even to be New York fashion models and clearly, some of them are near death. But on the second row from the bottom, seven men across from the left, is Elie Wiesel himself.

I have viewed this picture many times before, but I enlarged it on my computer so I could take a closer look at Elie Wieselís face. It was then that something else in the photograph caught my eye. Something I had not noticed any of the other times I have looked at this picture. It was the prisonerís pillows.

What was it about them? Well, there werenít any. At least, not in the way I understand pillows. These Buchenwald inmates were using their metal dinner bowls as pillows. Some of the inmates have tried to roll up a few bunches of their tattered blankets to make the metal bowls more comfortable, but others have not even bothered to do that. They were probably too weak from malnutrition to care. And it was this small detail from a real concentration camp, metal pillows, that revitalized my hatred for Life Is Beautiful, made me remember what a manipulative and morally bankrupt film it was and made me want to trash it to hell.

Filmmakers can choose any kind of story to make into a film. So, it is fair to ask them why they choose particular stories over others and if they choose the Holocaust or Concentration Camps as subjects for their films, you are allowed to ask them why. Sad to say, but some people choose to make films about the Holocaust for less than noble reasons. As one wag put it, ďThereís no business like Shoah businessĒ, and what that critic meant was that there is virtually no downside to making a Holocaust film.

Even if your film never makes a dime, it is unlikely to be criticized harshly or thought to be a failure because well, itís about the Holocaust so it must be good, right? I mean really, what is so wrong with the Italian comic actor/director Roberto Benigniís film Life Is Beautiful?

Let me recap the story for you in case it has slipped your mind. Life Is Beautiful begins in the Tuscan region of Italy in 1939 as Roberto Benigni, playing a sweet natured goofball named Guido Orefice manages to get a job in his uncleís hotel as a waiter after a series of charmingly comic misadventures. But Guidoís real dream is to open a bookstore some day. Then, due to some charmingly comic misadventures, Guido continues to bump into Dora (Nicoletta Braschi), a pretty woman who happens to be engaged to a prominent member of the local fascist government. But Guido is smitten with her and through another series of charmingly comic misadventures (including a romantic abduction on a green horse), Guido Orefice ends up marrying Dora.

What?

Guido Orefice is Jewish, you ask unbelievably? I know he doesnít look Jewish, is ďOreficeĒ a Jewish name perhaps? Not according to Ancestry.com, which lists ďOreficeĒ as Southern Italian in origin and it means jeweler. Letís examine this further, now, Guido Orefice does not pray in a synagogue, does not have a mezuzah on his door or a Menorah in his window or a Star of David around his neck. He does not observe any Jewish customs or Jewish dietary rules nor does he observe any Jewish holidays and he never, ever, even once says ďOy Vey!Ē So, we pretty much have to take it on his word that heís Jewish. But hey, thatís good enough for the Naziís because they send him and his family to a concentration camp.

And it is here in the concentration camp that Guido decides to hide the truth about the realities of life in the camp from his son. Despite all the horror and death around him, Guido tells Giosue that they are now involved in a game where the goal is to amass 1000 points and that First Prize is a real live, full sized, actual working military tank!

And the kid believes this completely! And why shouldnít he? Itís not like his father would ever lie to him. True, Daddy never told Giosue he was actually Jewish and apparently Momma didnít know that either because she never mentioned it, but hey, how many of us can honestly say that at one time or another we havenít forgotten what religion we practice.

Then, through a final series of charmingly comic misadventures in the concentration camp, yes, you read that correctly, Guido manages to hide the real truth about the camp from his son who ends up surviving the ordeal although Guido does not and the impossibly cute Giosue is still alive when the Americans finally come rolling into the camp with their tanks at the end of the film proving once and for all that life in a concentration camp does not have to be dreary. In fact, with a little imagination, a drop of faith and a soupcon of love, it can be ďjusta one bigga laugh!Ē (Thank you Joe Queenan.)

Truly, when this film ended, I saw people weeping openly as they shuffled awestruck into the lobby, touched by witnessing the sheer power of love and the human spirit as it once again triumphed over adversity.

That was their reaction. As for me, I wanted to vomit.

Now, let me be clear here, to those of you who liked the film, thatís fine and my intense dislike of it is definitely the minority opinion. So, like those of you who believe in ESP, communication with the dead or Creationism, Iím not going to try and change your mind. All I can do is tell you why I didnít like the film Life Is Beautiful. You will either find my opinions compelling or you will disagree with them. But if I can at least get you to think twice about Life Is Beautiful, I will have succeeded.

So, here goes. First, a little bit of Roberto Benigni goes a long way with me. I do not think heís the ďItalian Charlie ChaplinĒ as some critics have dubbed him, I think heís more like the ďItalian Robin WilliamsĒ (thank you Ron Powers).

So, instead of translating the actual work rules and mealtime procedures, Benigni explains that everyday, the person with the least amount of points has to wear a sign that says ďJackassĒ on it. Benigni explains that if anyone is afraid or asks for their Mommy, they will have points deducted. Furthermore, you can lose points by being hungry and asking for lollipops or bread with strawberry jam. Benigni says that the Nazi guards themselves are part of the game and play the parts of ďmean guys who yell a lotĒ and explains that the reason they are not around all the time is because they are in a perpetual game of Hide And Seek. All of this is accepted with pop-eyed delight by his son Giosue and frightened, shuffling confusion by the other Italian prisoners.

Personally, if I were there, I would have strangled the life out of Benigni with my bare hands for that stunt. Suppose Iím one of the new prisoners and I donít speak German, well, now I donít know some of the rules I might need to know that could possibly keep me from being shot on the spot.

Amazingly, people around me in the theater were laughing at this scene while I was screaming, ďa hundred Italians, in Italy, allies of Germany and nobody speaks a single word of German?Ē Likewise, the Naziís had a concentration camp in Italy full of Italian Jewish prisoners and none of the Germans spoke any Italian? They were allies werenít they? At least until late in the war they were. One more thing, didnít any of those Nazi guards happen to notice that a five-year-old child was standing there gawking at them?

I have seen it reported that Roberto Benigniís father spent time in the notorious Bergen-Belsen concentration camp during the war and that Roberto actually used some of the stories his father told him for inspiration and story fodder. Let me say I donít believe him. Iím not saying Benigni Senior was never in a concentration camp, I am saying that young Roberto must have totally misunderstood or remembered what his father told him incorrectly because nothing in Life Is Beautiful has the ring of truth to it.

If Life Is Beautiful had portrayed Roberto Benigni's character as a man who was insane, then perhaps I could have accepted his lunatic behavior. But what I witnessed in this film was something morally repugnant and more reprehensible than child abuse. By lying the way he did, he was actively taking away his childís ability to adapt and survive in this horrible situation. You donít help the kid by pretending whatís happening is not happening, anymore than pretending that your house is not on fire is a good strategy for surviving the fire. As far as I know, there are no accounts of anyone surviving the Concentration Camps by pretending that what the Naziís were doing was only a game.

Now, I have been told by many that I am taking this film way too seriously. That Life Is Beautiful is meant to be a fable and not a realistic depiction of life or survival in a concentration camp, sort of, ďItís only a movie Michael, get over it.Ē It is true that I sometimes take seemingly insignificant things too seriously.

In truth, nearly 2/3ís of the people sent to the camps died there. So, in the case of pure numbers, the most common story coming from the camps was death. When you read accounts of survivors, they almost to a person say that the reason they survived was because of. . .well, they almost all donít know why they survived.

In most cases it simply came down to luck. The kind of brutal definition of luck that Aristotle used when he said luck is when the arrow hits the other guy. So many people survived when the person standing right next to them was shot by an SS guard that it can damage your faith. But virtually no one survived because they had faith, or an excessive amount of life spirit or anything like that.

One reason so many filmmakers try to tell stories from the concentration camps by using the predictable devices of melodrama is that it adds a level of comprehensibility to a subject that is truly incomprehensible. The clichť of love conquering all or the beneficence of God is actually insulting to the people who survived the Nazi horror and it should be. To use the tired, falsely cheerful and uplifting values normally associated with a bad TV movie to explain away people surviving Treblinka is unforgivable. It came down to luck and no one likes to admit that we really are all in this universe because of luck.

I said earlier that I had a conflict in my opinions about the portrayal of the Concentration Camps in films, but ultimately, if I had to make a choice, I would say that dramatic portrayals should be allowed, but they should NOT be critic proof.

Just because someone chooses the subject of the Holocaust, they should not be given a pass on their work. If anything, the writers, directors, actors, producers, poets, painters and playwrights who attempt this topic should be held to a higher standard and if they produce something as astonishingly moronic and insulting as Life Is Beautiful, they should be justly criticized.

But this in no way should be interpreted as a call to forget the Holocaust. I know people get tired of hearing about it, imagine what it was like living it. If you think it canít happen again, turn on some pea-brained Right Wing radio gasbag sometime. With their irrational fear of Mexicans, Muslims, gays or anyone not exactly like them, they tend to make people like the fanatical racist Heinrich Himmler sound as benign and rational as Mr. Rogers, but nowhere near as smart.

I would like to offer a last quote from Elie Wiesel who explained that one of the duties of the concentration camp survivors is to be a witness. ďFor us, forgetting was never an option. Remembering is a noble and necessary act. It is incumbent upon us to remember the good we have received, and the evil we have suffered.Ē

And please remember that people make films for all kinds of reasons and not all of them are noble. |

Forgive my

overly provocative title; itís just my way to grab the readerís

attention. So, if I have your attention, please read further to

discover why I think Life Is Beautiful is a repellent film.

Forgive my

overly provocative title; itís just my way to grab the readerís

attention. So, if I have your attention, please read further to

discover why I think Life Is Beautiful is a repellent film.

Cut to five

years later, Guido has opened his bookstore and now has an

impossibly cute son named Giosue (Giorgio Cantanari). But the

familyís happiness is coming to an end, because you see, itís 1944

and Guido Orefice has a lot to worry about because heís Jewish.

Cut to five

years later, Guido has opened his bookstore and now has an

impossibly cute son named Giosue (Giorgio Cantanari). But the

familyís happiness is coming to an end, because you see, itís 1944

and Guido Orefice has a lot to worry about because heís Jewish.  But for

those who have not seen the film, there is one scene that has become

rather famous. It is the clip shown most times on film programs and

the one mentioned in almost every review of the film. It occurs a

little past the mid-point when Roberto Benigni and his son have just

arrived at the concentration camp with a bunch of other new

prisoners and they are put in a barracks with some camp veterans.

But Benigni has managed to hide his son from the Naziís view. And

now, a stern Nazi guard appears to tell the new inmates the rules of

the camp. Benigni has already told his little boy that they are now

part of some grand glorious game and he has to think quickly to keep

up the ruse. When the Nazi guard asks if anyone knows German,

Benigni raises his hand and steps forward to translate for the

Italians. But Benigni does not know German and he purposely

mistranslates the camp instructions into rules of the ďtank gameĒ

for Giosue.

But for

those who have not seen the film, there is one scene that has become

rather famous. It is the clip shown most times on film programs and

the one mentioned in almost every review of the film. It occurs a

little past the mid-point when Roberto Benigni and his son have just

arrived at the concentration camp with a bunch of other new

prisoners and they are put in a barracks with some camp veterans.

But Benigni has managed to hide his son from the Naziís view. And

now, a stern Nazi guard appears to tell the new inmates the rules of

the camp. Benigni has already told his little boy that they are now

part of some grand glorious game and he has to think quickly to keep

up the ruse. When the Nazi guard asks if anyone knows German,

Benigni raises his hand and steps forward to translate for the

Italians. But Benigni does not know German and he purposely

mistranslates the camp instructions into rules of the ďtank gameĒ

for Giosue. To those

people who tell me to accept Life Is Beautiful with a grain

of salt, I can only say, go talk to, or read the accounts of people

who were actually in a concentration camp. You will learn that

survival in the camps cannot be reduced to a cheery excess of ďhuman

spiritĒ. The people who actually went though the concentration camp

experience canít stomach the travesty this film makes of the camps

and many have openly voiced the opinion that Roberto Begnini should

rot in hell. That may be harsh, but I donít necessarily disagree.

To those

people who tell me to accept Life Is Beautiful with a grain

of salt, I can only say, go talk to, or read the accounts of people

who were actually in a concentration camp. You will learn that

survival in the camps cannot be reduced to a cheery excess of ďhuman

spiritĒ. The people who actually went though the concentration camp

experience canít stomach the travesty this film makes of the camps

and many have openly voiced the opinion that Roberto Begnini should

rot in hell. That may be harsh, but I donít necessarily disagree.