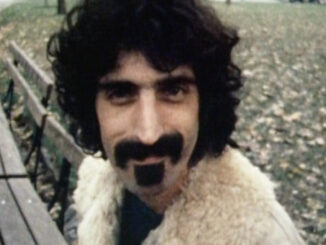

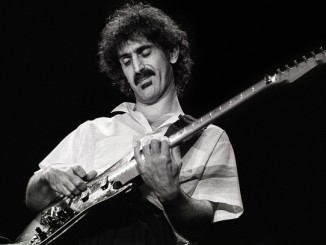

Whether you know it or not, if you have ever heard Deep Purple’s immortal rock classic “Smoke On The Water,” than you know a small part of the history of the Montreux Jazz Festival. The song tells of a fire that broke out in 1971 at the Montreux Casino in Switzerland – which where the Festival had been held for its five years of existence up to that point – during a Frank Zappa and the Mothers Of Invention concert. The casino did indeed burn to the ground, but there were no fatalities in part to, according to the song, “Funky Claude” who “was running in and out/He was pulling kids out the ground now.”

“Funky Claude” in this case is Claude Nobs, the founder of the Montreux Jest Festival and the subject of the documentary They All Came Out To Montreaux. It seems hard to separate Nobs from the story of the Festival itself. He was a life long music fan and the documentary lays out a case that it was almost through his own force of will and little else that brought the now venerated annual event into existence. And rather than just keep it within some strict definition of what jazz should be, Nobs had the foresight to expand the festival’s remit to cover blues, rock, world music and other emerging music genres. No taste-maker, it was all good to Nobs. Quincy Jones refers to the Montreaux Jazz Festival as the “Rolls Royce of all festivals in the world,” while Carlos Santana calls Nobs “the Merlin of jazz festivals.”

They All Came Out To Montreux is chockablock full of anecdotes and stories about Nobs and how his enthusiasm helped to shape the last several decades of music. There’s the time when, after hosting a dinner for David Bowie and the members of the band Queen, he urged the two rock legends to go off and just record something in a nearby studio. The result – their classic hit “Under Pressure.” Encouraging artists and fans alike seemed to be his lifeblood.

Outside of the pre-Festival, biographical section of the film, the documentary is composed almost entirely of performance footage from over the festival’s five decades. Nobs was enough of a fan to have cameras rolling from the very beginning of the festival and enough of a historian to ensure that everything was meticulously archived. But with the breadth of musical acts that performed at Montreaux and only a limited time to highlight as many as possible, it is somewhat frustrating that we don’t get to see fuller performances from many of them. One standout moment where do is when we see Nina Simone just sitting at an upright piano playing a haunting instrumental version of Simon And Garfunkle’s “Sounds Of Silence.” I dare say that it would be hard for any music fan to walk away from this film without at least the tiniest of urges to go to the Swiss archives for the festival to view full length performance footage.

(It should be noted that the ninety-minute documentary feature here is an edited down version of a BBC miniseries consisting of three one-hour episodes. Presumably there are more fuller performances in that iteration.)

The footage is accompanied by audio from interviews from a number of music notables from Herbie Hancock, Keith Richards, Van Morrison, Wyclef Jean, Gilberto Gil, Buddy Guy to name but a few, as well as a number of Nobs’ friends and colleagues.

Nobs sadly passed away in early 2013 after a skiing accident. The section is bracketed with a portion of David Bowie singing “Starman” in 2002 and Prince giving tribute to Nobs at the end of a 2013 performance of “Purple Rain.” The choice of these two artists feels significant. Each were important in influencing music in their own ways, and they would both die within months of each other just three years after Nobs. Is the film saying that what he created with the Montreaux Jazz Festival just as influential? The film may not give us enough information as to whether Nobs himself would agree or not with that assessment, but the argument is indeed there.