Journalist-turned-filmmaker Cord Jefferson’s debut feature American Fiction is at various times a hilarious, insightful and often scathing look at black stereotypes in modern culture and how and why they get perpetuated. A wryly funny critque of the entertainment industry balanced with an emotional story of a man coming to grips with his changing family dynamic, American Fiction is one of the best first features seen in a while, and certainly in contention for one of the best films of the year.

Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (Jeffrey Wright) finds himself at a crossroads in life. His career as a novelist has stalled, in part because what he is writing isn’t considered “black” enough by white editors at the publishing houses his agent has submitted his latest work to. His college literature students are very much not comfortable with the fact that they will need to deal with works, in this case Flannery O’Connor’s confrontational short story “The Artificial N*****,” that carry the ugly racist language of the time. While attending an authors conference, he sees a presentation from a new, bestselling African-Americn writer, Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), whose new bestselling novel, We’s Lives In Da Ghetto, he considers nothing more than “trauma porn.” And due to some reversals in his own family’s fortunes, he finds himself struggling to take care of his mother (Leslie Uggams) who is slowing succumbing to Alzheimer’s Disease.

Finally one evening in a fit of pique and frustrated that people only seem interested in just one small segment of what he considers to be a wide range of experiences being black, Monk sits down and bangs out what he considers a satire of the type of stories that Sintara’s book and others, seem to be telling. His agent isn’t amused, but at Monk’s insistence, sends the manuscript out under a pseudonym to various publishing houses. “I just want to rub their noses in the horseshit they put out,” Monk states. So he is very much surprised when not only are publishers interested in acquiring the novel, they are willing to pay far more than he has ever received for any of his other books. Monk now finds himself having to roleplay the fictional author he created for the publishers and some film executives who are interested in the book’s movie rights, while keeping that secret from his family and the new love in his life.

Thematically, director Jefferson is treading some of the same ground that another young black filmmaker trod some thirty-five years ago. I am referring to writer/director/actor Robert Townsend’s 1987 debut Hollywood Shuffle, in which he stars as a struggling Hollywood actor disillusioned with the pimps and drug addicts roles he has been offered. Unfortunately, the more things change the more they stay the same. But where Townsend’s film used his main character’s struggle to find a non-demeaning acting role as a spine for a number of comic sketches/daydreams that lambasted the use of stereotypes in popular entertainment (eg, “Black Acting School”), Jefferson pretty much stays firmly in Monk’s reality, serving up very little big comic exaggeration of the patent absurdities of his story. In fact, there are only two times when Jefferson breaks the reality of his film, the first being when Monk starts writing his angry satirical take on Sintara’s novel and two characters appear in his study, acting out, and sometimes directly questioning Monk, as he is writing. The second is a spoiler I leave for you to discover as you watch the film.

Monk struggles reconcile his higher ideals and aspirations against the very lucrative prospect of selling out (a term not actually used in the film, but very much implied in certain conversations), and Jefferson delicately balances this with the familial issues that he is dealing with. It gives his lead some nice dramatic meat to balance out the absurdity of his professional life.

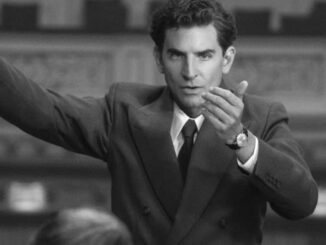

Jeffrey Wright’s performance here as the frustrated novelist Monk is a career highlight and a bit of a revelation. Outside of his appearances in recent Wes Anderson films, Wright has not had the chance to really demonstrate some comedy chops. Monk is a complex character and Wright navigates the distances between his intellectually acerbic and emotionally fragile sides with ease. And where some comedic actors may be tempted to go big for certain reactions for the laugh, Wright often goes small, giving just barely registered expressions of disbelief and disgust to what he is seeing going on in the publishing world. A slight wince of disgust at something earns a laugh as we watch him struggle to keep his cool. And Jefferson’s crackling sarcastic comments are a perfect fit for Wright’s cool delivery.