We originally reviewed the documentary Richland in our coverage of this year’s Tribeca Film Festival. We represnt that review now ahead of its screening at the Philadelphia Film Festival tomorrow.

On its surface, Richland, Washington appears to be just a quiet Pacific Northwest town. It is the kind of town where most people know each other and they all come out on fall Friday evenings to root on the local high school football team. But Richland has a history rooted in World War Two and the birth of the atomic bomb.

The town of Richland was basically built during World War Two to house the families of workers at the nearby Hanford Engineering Works, a facility that refined uranium for the Manhattan Project. Initially a very much planned community, the city continued to grow after the war ended, thanks in part to the continued need for uranium in the nuclear arms race with the USSR. That

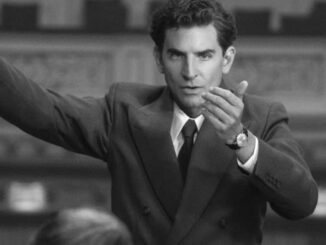

Director Irene Lusztig’s documentary Richland, takes us inside that town, painting a portrait of how its residents are now just starting to come to reckon with its place in history. At times contemplative, at times journalistic, Lusztig has turned her camera on the town residents and let them tell their story in their own words. To provide some historical context, she often intercuts archival footage from the 1940s through the 1980s, illuminating the town’s unique place in the 20th Century. The result is a unique insight into a town at a crossroads, struggling to come to grips with their own complicated history.

For some, the town’s history is a source of pride. Being “proud of the cloud” is described by one towns person as part of the civic identity of Richland. The high school football team’s nickname is the Bombers with a stylized mushroom cloud logo emblazoning the back of their letterman jackets. But we see that there are students who do not think that a nuclear explosion is necessarily appropriate iconography for a high school. As one student remarks “It’s hard to take pride in our school when the motto used to be ‘Nuke ’em until they glow.'”

“We don’t need to change it,” argues another lifelong town resident in regards to the high school logo. “We need to explain to the outside communities we don’t look at this as what was used to kill people, this is something we accomplished.” How the viewer wants to parse that sentence is entirely up to them.

The split over the town’s complicated history falls mostly along generational lines, though not completely. A high school teacher interviewed also feels the mushroom cloud explosion logo is inappropriate for kids. A townswoman is trying to draw attention to a host of neo-natal deaths in the late 1940s evidenced by a stroll through a local cemetery, most likely as a result of the proximity of the Hanford Engineering Works site. While high school students debate whether President Harry Truman was justified in deploying the atom bomb against Japan, there are numerous fundraisers in town for people fighting cancer. An older couple talk about how beautiful a nearby rive is, but that they would never fish in it.

With the way that the town’s history is so baked into its culture – Not just in terms of high school sports team nicknames, but down to things like street names like “Nuclear Lane” and “Proton Lane” – any change might be difficult and slow to come.