Film directors have often spoken out about the conditions in theaters where their movies are being exhibited, often criticizing profit-driven decisions to not replacing projector bulbs as they begin to loose their brightness or sound systems that are not properly calibrated. And that is understandable; they want everything to be perfect for the audience. Sometimes, though, that perfection of presentation will require some extra, out of the ordinary adjustments. Such as in the case of David Lynch’s surrealist neo-noir thriller Mulholland Drive.

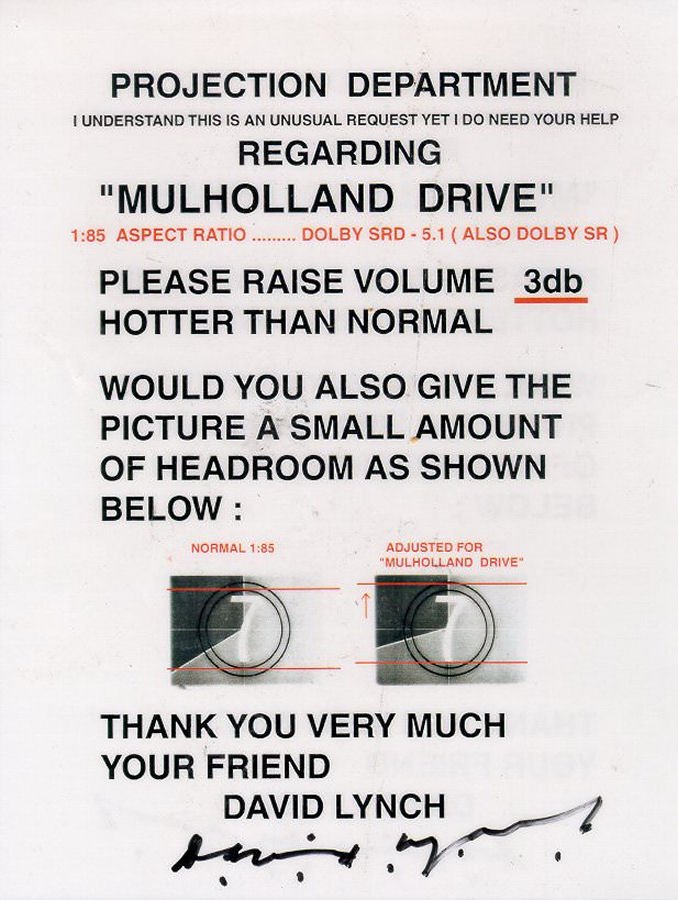

For the release of Mulholland Drive in the fall of 2001, Lynch penned a letter which went out with prints of the movies with very specific instructions as to how the film should be projected. As you can see below, Lynch want projectionists to set the audio levels for the film a bit higher than they normally would. And for good reason.

Lynch is very attentive to the sound design of his films. Whereas most directors use musical score to help set am ood that they want for any particular scene, Lynch is more apt to use sound. And his work with sound really reaches its apex with Mulholland Drive. Ethereal winds and atmospheric low-end rumblings help to create a tense, anxiety-ridden mise-en-scène with sharp punches of the sound of car crashes and the like serve to jolt us in our seats. Raising the house audio in theaters helps to accentuate the power of Lynch’s sound mix.

The instruction about the framing of the picture is of interest as well, and that is due to the film’s origin. Mulholland Drive initially started off as a television project, with a bulk of the film being repurposed from the pilot that Lynch shot in early 1999. That version was commissioned by ABC, whom Lynch worked with on Twin Peaks. However, although they were the ones to approach Lynch about collaborating on a new TV project, the network decided to ultimately not go ahead with the series after they saw the pilot. Undeterred, Lynch decided to rework some of the material in the pilot, write an additional 18 ages of script to shoot some new scenes and turned it into a self-contained story rather than the open-ended serialized story that the pilot was formatted as.

(Previously, when Lynch was crafting the two-hour pilot for Twin Peaks, he shot some additional footage to give the story some closure in order to turn it into a theatrical film for release overseas. This material was then re-incorperated back into the series in episode three of the first season as the famous Red Room dream Kyle MacLachlan’s FBI Agent Dale Cooper has at the end of that episode.)

As it was original created with an eye for widescreen television, Mulholland Drive was originally shot in the 16:9 or 1.78:1 aspect ratio. However, when he reconceived the material as a feature film, Lynch changed the aspect ration as 1.85:1. The matting in the projector creates that aspect ratio, with the adjust ment slightly upwards of the masking plates better centers the image on the screen.

Do such special adjustments ultimately impact the experience of the film? For the discerning cinema-goer, of course. And let’s face it, David Lynch, although a fairly well known director, is not exactly a mainstream movie maker. And Mulholland Drive is Lynch’s best work and has landed on the recently released British Film Institute/Sight And Sound poll of the greatest films of all time in the number eight position. So if this is the way that Lynch wanted the film projected and these are the results, who are we to argue?