We have already seen how the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has worked to keep the sale of older Academy Award statuettes from happening. Oscar winners after 1950 are forbidden from selling their awards via an agreement that they sign when they receive the award. But even then, the Academy still tries to exercise some control over what happens to the Oscar statuettes issued out before 1950.

Without a doubt, Citizen Kane is one of the greatest films ever made. Writer/director Orson Welles crafted a movie that presented and explored a complex character and his impact on the first half of the 20th century. The character was seen as a scathing attack on newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. At least seen that way by Hearst; Welles would always say that the character was inspired by a combination of many different people.

Hearst offered to buy the negative of the film before it was released, in order to destroy it. After the studio flatly refused him, the newspaper magnate embarked on a smear campaign to ruin Welles and the movie any way he could. Hearst owned newspapers were ordered not to carry advertisements or reviews for the film. Hearts’s syndicated Hollywood gossip columnist Louella Parsons blasted the picture and would spread insinuations that Welles was a communist.

But despite Hearst’s attempts to squash the film, Citizen Kane did get released, but to mixed results. While it was a critical success, it proved to be a dud at the box office. No doubt Hearst’s campaign against the film had at least some effect.

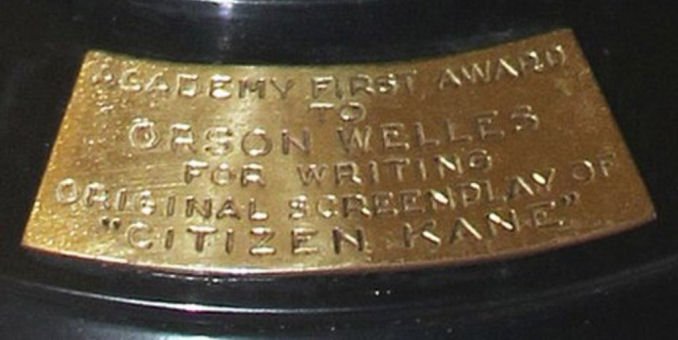

Hollywood certainly recognized the quality of work of their peers and nominated it the film in nine categories for the Academy Awards that year. With nominations in three categories – Best Actor, Best Director and Best Writing (as the category was known at the time) – Welles himself only took home the only trophy the film would win; the one for Best Writing, an honor he would share with his co-screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz.

Welles was already no fan of the Academy and so was boycotting the ceremony. Mankiewicz also decided to be a no-show, calling up RKO Radio president George Schaefer the morning of the ceremony and asking him to accept the award on their behalf should they win.

It is probably just as well that Welles and Mankiewicz passed on attending the ceremony as reports from the evening stated that there were scattered boos and hisses whenever Citizen Kane was announced amongst a category’s nominees. Hearst’s libel running deep in the Academy. Or perhaps, as Peter Bogdanovich speculated in his book of conversations with the director, This Is Orson Welles, “Welles was the outsider, and not a humble one, either… [T]he Hollywood majority just didn’t like him.” Bogdanovich also speculated that the one Oscar that Citizen Kane did win was most likely awarded more on the strength of voters’ appreciation of Mankiewicz’s body of work rather more than anything else.

After the trophy was delivered to Welles, no one is quite sure what he did with it. In This Is Orson Welles, Welles stated that he “always pretend[s] I never got an Oscar.” Welles died in 1985, but it wasn’t until his third wife Paola Mori died the following year and their daughter Beatrice inherited Welles’s estate, was it determined that the Oscar was missing. It was generally assumed that, with Welles essentially couch surfing among some of his Hollywood peers for a portion of his later life, it was misplaced somewhere along the way. He certainly had no sentimentality towards the object. Beatrice petitioned the Academy for a replacement, and was granted a new Oscar trophy in 1988. The matter seemed settled.

However, in 1994, the original Oscar surfaced in auction at Sotheby’s in London. Cinematographer Gary Graver claimed that the director had given him the Oscar in 1974 as they were working on the film The Other Side Of The Wind. (Graver also shot F For Fake for Welles.) Graver had sold the statuette to a company called Bay Holdings for $50,000, who then brought it to Sotheby’s for resale with a minimum reserve bid of $250,000. When contacted by Sotheby’s, Beatrice Welles sued both Graver and Bay Holdings. At trial, the court determined that the Oscar statue was a prop for the film, and therefore was given to Graver by Welles for safekeeping for future filming and not as partial payment for his services, as Garver claimed to understand Welles’s intention. The sale was halted and the Oscar was given back to Beatrice Welles.

Welles herself went on to attempt to sell her father’s Academy Award in 2003 as a way to continue funding her life’s pursuit of animal rescue. Since sale of the replacement Oscar she was given in 1988 was forbidden under the Academy’s agreement, she decided that she would part with the original. Besides, in a LA Times essay published in March 2004, Welles reasoned that her father was not particularly impressed with awards and “to sell the one thing that had no value to him, but was of great value to others, perhaps was not so bad after all.”

When news of the impeding auction broke, the Academy objected. Hoping to stop the sale, they claimed that in the agreement Beatrice Welles signed for the replacement Oscar statue was a clause that also retroactively covered any Academy Awards won prior to the 1950 agreement. Welles countered that she was not the original recipient of the Oscar awarded in 1941, her father was, and therefore was not bound by that particular part of the agreement. When the matter was brought before a judge, the judge agreed with Welles, declaring that the Oscar was her property to do with as she wished.

Welles finally sold the Oscar to California non-profit philanthropic organization The Dax Foundation. The Dax Foundation went on to try and resell the statuette in 2007, though the reserve price asked for at the time was not met. The Dax Foundation tried again in December 2011. When the hammer fell on the sale at the Los Angeles auction house Nate D. Sanders, the Oscar statue, which was thought to have a reserve price somewhere between $600,000 and $1 million, fetched a price of $861,542. The purchaser remained anonymous, although magician David Copperfield, who reportedly owns props from Citizen Kane‘s production, was one of the bidders.

Perhaps spurred on by the amount that the Welles Oscar brought in, Mankiewicz’s own Academy Award for Best Writing for Citizen Kane would sell the following February for $588,455. It was one part of a group of 15 Oscar statues the auction house was selling for a single unidentified seller.