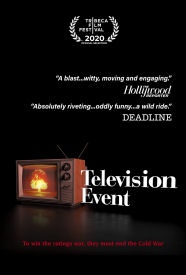

(Television Event screened yesterday at the Philadelphia Film Festival and will have a second screening on Saturday, October 30th.)

(Television Event screened yesterday at the Philadelphia Film Festival and will have a second screening on Saturday, October 30th.)

There is no denying that television impacted culture and society in ways almost too numerous to count throughout the second half of the 20th century. It often brought us together as a society, it changed how people were informed and entertained and at times it even divided us as a society. But did television save us from the nightmare of nuclear war?

That is the question that lies in the heart of documentarian Jeff Daniels’ film Television Event, which takes a look at the genesis, production and controversy surrounding the television movie The Day After, which aired on ABC in 1983. The film got its start as an idea from network president Brandon Stoddard, who was looking for subjects for their movie-of-the-week lineup which frequently pulled ideas from then current events as a way to captivate audiences. Stoddard’s vague idea to do a film about nuclear war would become The Day After, a three-hour television event that looked at the lives of some average Midwestern townspeople leading up to and through a nuclear exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union. And Stoddard did not know what firestorm of criticism he would ultimately be in for from conservative pundits all the way up to the White House.

But for director Nicholas Meyer, The Day After was more than just about examining a topical issue. He was horrified by the ascendancy of Ronald Reagan to the presidency in 1980 and his peace through strength philosophy in dealing with the Soviets. He knew what the devastating consequences of a nuclear war would be and was not convinced that Reagan did. He saw the unprecedented project as a way to really illustrate the horrors of what Reagan’s policies could lead to. “I wanted the film to be like a Public Service Announcement,” he states.

Meyer and his crew did their job a bit too well for some people’s liking. Network censors were not happy with the realism that the script noted, demanding that the horror of nuclear war be scaled back time and again. Meyer fought their notes at every turn, earning him the reputation of being “difficult” with some of the network brass. Meyer counters with, “Nine times out of ten, when someone is called difficult, they are just passionate about what they are doing. They want to get it right.”

And while that era of practical effects could come nowhere near showing how complete the devastation at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was, the film still packed a wallop with viewers. Actress Ellen Anthony, who plays the younger daughter Jolene in one of the film’s central families and was a local in the film’s Laurence, Kansas shooting location, described her home town as a warm, welcoming place but that once the production team arrived to begin shooting, “We surrendered our innocence in a way to tell a serious story.” Later, while watching the film again on camera, she cries, pointing out that it was her own fifth-grade class friends that you see vaporized during the missile attack sequence.

The Day After arrived at a time when there was already a growing divide in the public’s opinion on Reagan’s hard-line stance against the Soviet Union. Some on the right denounced the film without ever seeing it, like national moral scold Jerry Falwell. An editorial in the New York post said that Meyer was doing the work of Soviet Premier Yuri Andropov. (The movie does not state who started the nuclear exchange.) Others saw the film as a wake-up call illustrating the horrors of what would befall not just the nation, but the world, if cooler heads did not prevail, and nuclear weapons were let loose.

The Day After arrived at a time when there was already a growing divide in the public’s opinion on Reagan’s hard-line stance against the Soviet Union. Some on the right denounced the film without ever seeing it, like national moral scold Jerry Falwell. An editorial in the New York post said that Meyer was doing the work of Soviet Premier Yuri Andropov. (The movie does not state who started the nuclear exchange.) Others saw the film as a wake-up call illustrating the horrors of what would befall not just the nation, but the world, if cooler heads did not prevail, and nuclear weapons were let loose.

Daniels presents his case for The Day After‘s historical impact well here. Shortly before the film’s airing on ABC, the White House requested a copy of it for President Reagan and his wife to watch. Later, in his memoirs, Reagan would state that the film depressed him. The film argues that the film’s gritty realism forced Reagan to reconsider his more cavalier attitude towards nuclear sabre rattling, forcing him to adopt an attitude that nuclear war was unwinnable. There is a wealth of behind-the-scenes footage used to illustrate the path the film took to completion and contemporary news footage to show controversy swirling around the film itself as well as Reagan’s shift in policy.

So did Daniels get it right? Did The Day After effect some change on national policy? On a personal level, it is hard to say. I was barely fourteen at the time The Day After aired. I had seen some of the promotion and was certainly interested in seeing the movie. Although my parents were fairly cool about what me and my younger brother could do or watch – they let us continue to play Dungeons & Dragons after it had been denounced from the pulpit of our church during the “Satanic Panic” paranoia from around the same time – I have a distinct memory of them taking us out of the house the evening that The Day After aired, ostentatiously in my mind to this day to keep us from seeing it. (I would catch up with it a few years later in college.) And as a high school freshman, I was coming home in the afternoon to put on MTV, not CNN.

So we’ll leave it to the historians to debate about The Day After‘s ultimate impact. But Television Event gives a strong and compelling argument not just for the film’s place in the history of the medium but in the social-political history of the 20th century itself.