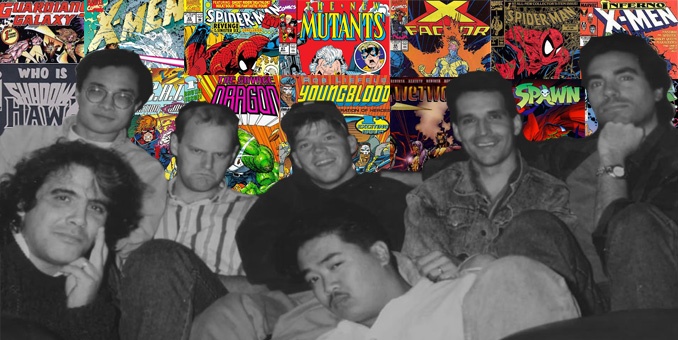

The 1990’s comic book boom arrived on the backs of the superstar artists. The person drawing the comic could mean the difference between a comic that sold a couple hundred thousand copies and one that sold two million copies. Hot artists were everywhere but a lot of them seemed end up at Marvel Comics.

Like, Jim Valentino. Valentino got his start in the 1970’s doing small-press autobiographical comics. In the 1980s, he created normalman, a hilarious parody of the then-current comic book industry. This led him to Marvel, where he wrote ad drew issues of their What If…? reboot and an updated series featuring the company’s team of the future, Guardians of the Galaxy.

Then there was Marc Silvestri, who got his start drawing issues of DC’s horror comic books in the early 80s. He then moved over to Marvel where he got a job drawing the King Conan comic book which led to a run on Web of Spider-Man and then a run on Uncanny X-Men and then a run on Wolverine.

Then there was Marc Silvestri, who got his start drawing issues of DC’s horror comic books in the early 80s. He then moved over to Marvel where he got a job drawing the King Conan comic book which led to a run on Web of Spider-Man and then a run on Uncanny X-Men and then a run on Wolverine.

Also, Todd McFarlane, an artist who sent in over 700 submission before his big break: a four-page backup story in the Epic Comics’ title, Coyote. He eventually became the artist on DC’s Infinity, Inc. title. He worked on several issues of Detective Comics before moving to Marvel to take over art chores on Incredible Hulk. His fame reached the stratosphere when he started drawing Amazing Spider-Man. He became so popular that Marvel created a new title for him to write and draw, Spider-Man.

Also, Todd McFarlane, an artist who sent in over 700 submission before his big break: a four-page backup story in the Epic Comics’ title, Coyote. He eventually became the artist on DC’s Infinity, Inc. title. He worked on several issues of Detective Comics before moving to Marvel to take over art chores on Incredible Hulk. His fame reached the stratosphere when he started drawing Amazing Spider-Man. He became so popular that Marvel created a new title for him to write and draw, Spider-Man.

Erik Larsen came up through the ranks of the independent comics, having started at companies either self owned or owned by friends in the early 1980s, most notably Megaton Comics. This led to work at AC Comics and Eclipse Comics, which got him noticed by DC Comics. He drew the Doom Patrol title for them before moving over to Marvel, where he took over for McFarlane on Amazing Spider-Man and Spider-Man.

Erik Larsen came up through the ranks of the independent comics, having started at companies either self owned or owned by friends in the early 1980s, most notably Megaton Comics. This led to work at AC Comics and Eclipse Comics, which got him noticed by DC Comics. He drew the Doom Patrol title for them before moving over to Marvel, where he took over for McFarlane on Amazing Spider-Man and Spider-Man.

You also have Whilce Portacio, who broke into comics the way most people think you break into comics–by showing samples at the San Diego Comic Con. He was hired by editor Carl Potts first as an inker on Marvel titles such as Alien Legion and Longshot. He eventually move on to penciling titles like X-Factor, The Punisher and Uncanny X-Men.

You also have Whilce Portacio, who broke into comics the way most people think you break into comics–by showing samples at the San Diego Comic Con. He was hired by editor Carl Potts first as an inker on Marvel titles such as Alien Legion and Longshot. He eventually move on to penciling titles like X-Factor, The Punisher and Uncanny X-Men.

Carl Potts also helped Jim Lee get his first Marvel work. After meeting with Marvel editor Archie Goodwin at a New York City comic con, Lee was advised to go to Marvel’s offices where Potts gave him an assignment drawing Alpha Flight. Lee moved from that to Punisher War Journal to eventually taking over for Silvestri on Uncanny X-Men. It’s here where Lee’s popularity skyrocketed. Like McFarlane before him, Marvel gave him his own book, X-Men, for him to write and draw.

Carl Potts also helped Jim Lee get his first Marvel work. After meeting with Marvel editor Archie Goodwin at a New York City comic con, Lee was advised to go to Marvel’s offices where Potts gave him an assignment drawing Alpha Flight. Lee moved from that to Punisher War Journal to eventually taking over for Silvestri on Uncanny X-Men. It’s here where Lee’s popularity skyrocketed. Like McFarlane before him, Marvel gave him his own book, X-Men, for him to write and draw.

Finally, there is Rob Liefeld. Liefeld got his start in comic at 19 doing pin-ups for Megaton Comics. When Megaton folded, Liefeld made his way to DC Comics, where he would draw a number of short stories and the Hawk & Dove minseries. After that, Liefeld moved over to Marvel and started work on the New Mutants to great acclaim. Marvel, similar to what they did for Lee and McFarlane, cancelled New Mutants and allowed Liefeld to write and draw its follow up, X-Force. He was also famously featured in a Levi’s ad directed by Spike Lee.

Finally, there is Rob Liefeld. Liefeld got his start in comic at 19 doing pin-ups for Megaton Comics. When Megaton folded, Liefeld made his way to DC Comics, where he would draw a number of short stories and the Hawk & Dove minseries. After that, Liefeld moved over to Marvel and started work on the New Mutants to great acclaim. Marvel, similar to what they did for Lee and McFarlane, cancelled New Mutants and allowed Liefeld to write and draw its follow up, X-Force. He was also famously featured in a Levi’s ad directed by Spike Lee.

These men were the kings of the comic book industry. They made Marvel millions upon millions of dollars. They had lines at their tables at every comic book convention they went to. And while they made a fraction of what they brought into the company, they were making far more money than most of the comic book creators of the day. But they still weren’t satisfied.

The seven men had grown disenfranchised with the “work-for-hire” system in place at the big two comic book companies. While they had create enduring characters such as Deadpool, Venom, Bishop, Gambit and Cable, they had a lot more original characters they wanted to do but they didn’t want to give them to Marvel. They didn’t want to have the characters put into the hands of a creative team they didn’t approve of. And they didn’t want to get paid a pittance for their creativity.

The idea for going out on their own began after Larsen, Liefeld, and Valentino had dinner with Malibu Comics editor-in-chief Dave Olbrich. Olbrich expressed a desire to publish work by the creators, work the men would retain the rights to. The trio brought on McFarlane, and the four men knew to be successful they’d have to add on Jim Lee. Lee came aboard and brought along Portacio. A chance meeting at a comic con with Silvestri added him to the group and the founding members of Image were set.

The idea for going out on their own began after Larsen, Liefeld, and Valentino had dinner with Malibu Comics editor-in-chief Dave Olbrich. Olbrich expressed a desire to publish work by the creators, work the men would retain the rights to. The trio brought on McFarlane, and the four men knew to be successful they’d have to add on Jim Lee. Lee came aboard and brought along Portacio. A chance meeting at a comic con with Silvestri added him to the group and the founding members of Image were set.

Urban legends say that the Image Seven stormed into the office of Marvel president Terry Stewart’s office and demanded part ownership in the characters they created or the company itself. Stewart laughed at them and quickly said no. Then the group supposedly said that they were leaving to form their own company. Stewart (or someone else) reportedly shouted after them as they left the office about how replaceable they were. The truth is anticlimactic in comparison. They simply informed Stewart and editor Tom DeFalco they were leaving and then went to the DC Comics offices and relayed the same to them.

The partners agreed that they would only stay with Malibu for a year until they got the hang of the publishing side of running a comic book company. They came up with a charter that say that Image would not own a creator’s work, the creator would. They also said that one partner could not interfere creatively or financially in another partner’s work. Six of the partners set up their own studios under the Image umbrella: Todd McFarlane Productions, owned by Todd McFarlane, WildStorm Productions, owned by Jim Lee, Highbrow Entertainment, owned by Erik Larsen, Shadowline, owned by Jim Valentino, Top Cow Productions, owned by Marc Silvestri and Extreme Studios, owned by Rob Liefeld.

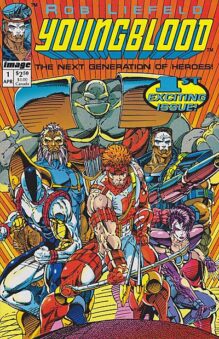

Liefeld was the first out the blocks in April 1992 with Youngblood, a paramilitary superteam with domestic and international strike teams. Two months later came Erik Larsen’s Savage Dragon, an amnesiac fin-headed alien, and Todd McFarlane’s Spawn, a demonic bounty hunter. In August of 1992, they were joined by Jim Valentino’s Shadowhawk, the tale of an HIV-positive urban vigilante, and Jim Lee’s WildC.A.T.S., a superhero team fighting an alien invasion. October 1992 brought Marc Silvestri’s Cyber Force, a team of cybernetically enhanced superheroes. Whilce Portacio missed the launch and would have to withdraw from Image due to an illness in his family. His offering, Wetworks, would arrive in 1994, published by Wildstorm.

Liefeld was the first out the blocks in April 1992 with Youngblood, a paramilitary superteam with domestic and international strike teams. Two months later came Erik Larsen’s Savage Dragon, an amnesiac fin-headed alien, and Todd McFarlane’s Spawn, a demonic bounty hunter. In August of 1992, they were joined by Jim Valentino’s Shadowhawk, the tale of an HIV-positive urban vigilante, and Jim Lee’s WildC.A.T.S., a superhero team fighting an alien invasion. October 1992 brought Marc Silvestri’s Cyber Force, a team of cybernetically enhanced superheroes. Whilce Portacio missed the launch and would have to withdraw from Image due to an illness in his family. His offering, Wetworks, would arrive in 1994, published by Wildstorm.

The company was an instant success. At the end of 1992, Image had four titles on the Top Ten Year-End Sales sheet. That was only second to Marvel and three more than DC had on the list. Some of the partners became richer than their wildest dreams. Todd McFarlane famously bought Mark McGwire’s then record-breaking 70th home run in 1998 for $2.6 million. They had their properties adapted into movies, TV shows, cartoons, and toy lines.

The company was an instant success. At the end of 1992, Image had four titles on the Top Ten Year-End Sales sheet. That was only second to Marvel and three more than DC had on the list. Some of the partners became richer than their wildest dreams. Todd McFarlane famously bought Mark McGwire’s then record-breaking 70th home run in 1998 for $2.6 million. They had their properties adapted into movies, TV shows, cartoons, and toy lines.

The company also became the home for creator owned projects. In the first year alone, they expanded their lines with books from popular artists such as Dale Keown, Sam Keith and Jerry Ordway. They also published superstar writer Alan Moore’s love letter to 1960’s Marvel, 1963.

Image’s success inspired other big name creators to try to duplicate their template. Once Image moved away from Malibu, the latter company became home to the short-lived Bravura imprint, where creators such as Jim Starlin, Howard Chaykin, Kevin Maguire and Marv Wolfman could try their hand at creator owned characters. Around the same time, Dark Horse created the Legend imprint to house works by a blockbuster array of writers and artists including John Byrne, Frank Miller, Arthur Adams, Mike Mignola and others. Image even got into the imprint game itself with Gorilla in 2000, and umbrella that was home to creator owned properties by creators Kurt Busiek, Tom Grummett, Stuart Immonen, Karl Kesel, Barry Kitson, George Pérez, Mark Waid, and Mike Wieringo.

But not everything was sunshine and roses with the early days of Image. The quality on the books were hit or miss, leaning towards “miss”. Clones of Wolverine and Cable were littered among the characters. Youngblood #1 famously had one of its two stories end in the middle of a fight scene, interrupted by an ad for the Rob Liefeld fan club. The story was never completed. And free from editorial deadlines, chronic lateness became a problem. In its first twelve months of existence Youngblood only published four issues.

With as many out-sized egos that the founding fathers of had, with more than one of the seven calling themselves “the bad boys of comics,” the possibility of strife was a real one. And it didn’t take long to happen. There was controversy amongst the partners aimed at Rob Liefeld, who was accused of using his position at Image to prop up his other comic company, Maximum Press, and he was also accused of poaching artists from his partner’s studios. Marc Silvestri removed his Top Cow studio from Image in 1996 over this. In September of that year, Liefeld resigned and Silvestri returned to Image. Image would lose another founding member in 1999 when Jim Lee sold his Wildstorm studio and the characters he created to DC Comics. One of the reasons was that he wanted to move away from the business side of running a company and get back into drawing comics. That only lasted a little over a decade, as in 2010 Lee became co-publisher of DC Comics.

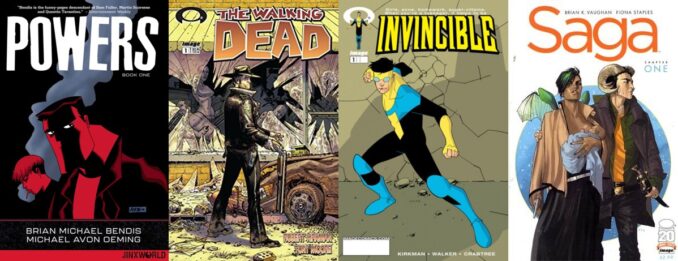

Now, we have all seen enough episodes of “E! True Hollywood Story” and “VH1’s Behind The Music” to expect that this is when the meteoric rise of Image would come to and end and the inevitable downward spiral would begin. Not so with Image. The company had started to diversify its content in between the departures of Liefeld and Lee. It would still be a publishing house for big name creators from the big two who wanted to own their own character. But it would become a home to talented, under the radar creators such as Brian Michael Bendis, Jonathan Hickman, and Robert Kirkman (his successes with The Walking Dead and Invincible led him to be offered the role of Image Partner). It published reprints of excellent independent book such as Bone, A Distant Soil, Strangers in Paradise and Stray Bullets in order to improve their distribution and exposure. Instead of hackneyed, poorly written books it became the home to brilliant creators pushing boundaries of the medium.

Now, we have all seen enough episodes of “E! True Hollywood Story” and “VH1’s Behind The Music” to expect that this is when the meteoric rise of Image would come to and end and the inevitable downward spiral would begin. Not so with Image. The company had started to diversify its content in between the departures of Liefeld and Lee. It would still be a publishing house for big name creators from the big two who wanted to own their own character. But it would become a home to talented, under the radar creators such as Brian Michael Bendis, Jonathan Hickman, and Robert Kirkman (his successes with The Walking Dead and Invincible led him to be offered the role of Image Partner). It published reprints of excellent independent book such as Bone, A Distant Soil, Strangers in Paradise and Stray Bullets in order to improve their distribution and exposure. Instead of hackneyed, poorly written books it became the home to brilliant creators pushing boundaries of the medium.

As a result, Image not only survived but thrived. It is as vital today as it was 30 years ago. Sure, only two titles from the initial launch are still around–Savage Dragon and Spawn–and only the former is still written and drawn by its original creator. But the company has grown into what its founders always intended it to be, a home where creators can reap the rewards of their creations.

Next time: We discuss why Ed Brubaker might not be the best poster child for creator’s rights.