The first sign or trouble was the pin set.Four round pins attached to a sheet of cardboard. Each pin tied into the Watchmen miniseries in some way. One pin was of the radiation symbol. One represented the mask of the Rorschach. One featured the series’ tag line, Who Watches the Watchmen, in Latin. And one pin featured a wall of blood creeping towards a clock about to strike midnight–a copy of the image that was on the back cover of every Watchmen issue. The back of the cardboard featured a synopsis of the series and reproduced autographs of the series creators Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. The set retailed for $4.95. Moore and Gibbons saw no money from the set. DC Comics. DC Comics said that the pins were a promotional item and, as such, the pair wasn’t entitled to royalties from their sale.

I wonder if this was when Moore and Gibbons got the feeling that DC would find a way to renege on the clause in their contract to transfer the rights to the Watchmen characters back to them. Because that is exactly what happened.

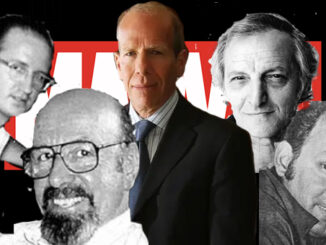

Alan Moore belongs right up with Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster, and Will Eisner as one of the legendary creators that changed the world of comic books forever. He got his start in England working primarily as an artist in underground publications. He eventually moved over to writing and got work fro IPC, Marvel UK and Quality Communications. It was at the latter where he wrote V for Vendetta, a vicious, dystopian future take on the future of Margret Thatcher’s regime, and Miracleman, a modern, grim and gritty updating of Britain’s Captain Marvel pastiche, Marvelman.

In 1981, Len Wein went on a talent search in the UK. Impressed with his writing ability, Wein hired Moore to take over a title close to Wein’s heart, featuring a character Wein co-created an decade prior–Saga of the Swamp Thing.

In 1981, Len Wein went on a talent search in the UK. Impressed with his writing ability, Wein hired Moore to take over a title close to Wein’s heart, featuring a character Wein co-created an decade prior–Saga of the Swamp Thing.

The hiring of Alan Moore for Swamp Thing was a defining moment in comic book history. It changed the world of comic books forever. For a medium that had always been defined as one aimed at children and buffoons, Moore’s intelligent and sophisticated scripts elevated the art form to literature. His success opened the doors for many more UK creators to make the leap to American comics, names such as Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison and Mark Millar. The writing of Moore and these men provided the skeleton that DC Comics built their Vertigo imprint around.

But his influence wasn’t always a positive one. His mature and dark writing style gave birth to the “grim and gritty” trend in comics. Only most creators outside of Moore didn’t include the nuance and substance he did. Those other creators thought by having their heroes curse and their heroines go topless they were just as grim and gritty as Moore. And the success that Moore had in revamping Swamp Thing led comic companies to revamp other characters, sometimes again and again, but seldom with the wit and intelligence Moore brought to his work.

Dave Gibbons was brought over to the UK at the same time as Moore. Gibbons was a self-taught artist who broke into comics as a letterer. He eventually got work as an artist for DC Thompson and IPC before Wein came calling. Like Moore, Gibbons was assigned work that was close to Wein’s heart–Green Lantern, a title written and edited by Wein. He started out doing the back up stories in the series before being promoted to drawing the main feature of the book.

Dave Gibbons was brought over to the UK at the same time as Moore. Gibbons was a self-taught artist who broke into comics as a letterer. He eventually got work as an artist for DC Thompson and IPC before Wein came calling. Like Moore, Gibbons was assigned work that was close to Wein’s heart–Green Lantern, a title written and edited by Wein. He started out doing the back up stories in the series before being promoted to drawing the main feature of the book.

As we mentioned last week, Moore and Gibbons were tapped by DC to bring the recently purchased characters from Charlton Comics in to DC’s fold. However, Moore’s treatment left the Charlton characters unusable in the future, so he was encouraged to change them into original characters. Moore and Gibbons changed the characters into pastiches of the original ones and the Watchmen was born.

Moore, being a superstar creator at the time, negotiated a sweetheart deal for him and Gibbons. He had a reversion clause written into his contract for Watchmen and V for Vendetta–which was left incomplete when it’s British publisher, Quality, went out of business–that said he and his artist would receive the rights to the characters once the books went out of print. The sweetheart deal got a whole lot less sweet when DC kept the two properties in print, even today, almost forty years later.

Moore, being a superstar creator at the time, negotiated a sweetheart deal for him and Gibbons. He had a reversion clause written into his contract for Watchmen and V for Vendetta–which was left incomplete when it’s British publisher, Quality, went out of business–that said he and his artist would receive the rights to the characters once the books went out of print. The sweetheart deal got a whole lot less sweet when DC kept the two properties in print, even today, almost forty years later.

Moore felt that DC entered into the deal never intending to take Watchmen out of print. As he put it in a 2006 New York Times interview:

“I said, ‘Fair enough,’ ” he recalls. ” ‘You have managed to successfully swindle me, and so I will never work for you again.’ “

And after 1989, he never did. The only time his work would appear under the wider DC Comics umbrella is when they bought Jim Lee’s Wildstorm imprint, where Moore created the “America’s Best Comics” line and the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen franchise, and brought it into their fold in 1999. He was promised that DC would leave him and his work alone under the new arrangement, but DC didn’t hold up to that promise and he left mainstream comics for good in 2005.

You can see why Moore has the right to be upset. But the idea that DC Comics kept Watchmen (and V for Vendetta) in print was just to spite Alan Moore ignore certain realities about the comic book business.

First off is the birth of the trade paperback collection. When Moore signed his reversion clause laden contract, comic book series and storylines being collected into trade paperbacks were not common. Sure, you’d have collections like the Fireside Marvel collections of the 1970s, but most of them would go out of print at some point. However, in the mid-1980s, Marvel and DC started experimenting with collecting their popular series and stories into trades. While Watchmen was being published, DC tested the trade paperback waters with collection of John Byrne’s Superman revamp The Man of Steel and Frank Miller’s dystopian future deconstruction of Batman, The Dark Knight Returns. These collections proved successful, and soon comic companies began collecting its seminal storylines into trade paperbacks, getting to the point where today practically every comic book story arc gets a trade paperback, and series that don’t get collected are rarer than those that do.

First off is the birth of the trade paperback collection. When Moore signed his reversion clause laden contract, comic book series and storylines being collected into trade paperbacks were not common. Sure, you’d have collections like the Fireside Marvel collections of the 1970s, but most of them would go out of print at some point. However, in the mid-1980s, Marvel and DC started experimenting with collecting their popular series and stories into trades. While Watchmen was being published, DC tested the trade paperback waters with collection of John Byrne’s Superman revamp The Man of Steel and Frank Miller’s dystopian future deconstruction of Batman, The Dark Knight Returns. These collections proved successful, and soon comic companies began collecting its seminal storylines into trade paperbacks, getting to the point where today practically every comic book story arc gets a trade paperback, and series that don’t get collected are rarer than those that do.

This brings up another reason why the series’ collection stays in print. With Watchmen, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons created arguably the best comic book series in the medium’s history. It has won numerous awards both in and outside the comic book field. It was the only graphic novel included on Time’s list of the 100 best novels between 1923 and 2005. And it is taught in literature classes around the world. It is the kind of evergreen property that always sells. Naturally, DC Comics would always keep it in print. Maybe the right thing would be for DC to pull it from the shelves so it could revert to its creators, but would you pass up a trade paperback that sells tens of thousands of copies at $25 retail year in and year out?

To their credit, outside of numerous new printings, DC Comics left the Watchmen alone in the comics. That is, until Paul Levitz stepped down as president and publisher in September of 2009. After that, the powers that be decided that the Watchmen cash cow had gone unmilked for far too long and decided to rectify that situation. But DC knew that any spin-off without the approval of Alan Moore would receive severe backlash. So DC made an effort to get that approval.

In a 2010 interview with Wired, Moore related an interesting offer he received from DC Comics:

In a 2010 interview with Wired, Moore related an interesting offer he received from DC Comics:

“They offered me the rights to Watchmen back, if I would agree to some dopey prequels and sequels So I just told them that if they said that 10 years ago, when I asked them for that, then yeah it might have worked. But these days I don’t want Watchmen back. Certainly, I don’t want it back under those kinds of terms.”

That offer came through the use of Dave Gibbons as an intermediary. The fact that Gibbons tried to convince him to take DC’s deal–in addition to his never thanking Moore for giving him his share of the Watchmen royalties–cause an irrevocable break in their friendship.

But DC continued on with their spin-offs anyway. Before Watchmen, a group of nine miniseries featuring prequels to Moore and Gibbons’ seminal work, was released in 2012. DC hired a number of the biggest names in comics at the time, including Darwyn Cooke, J. Michael Straczynski, Brian Azzarello, Steve Rude and Amanda Conner, but the prequel series received mixed reviews, paling in comparison to the original. Moore called the entire project “shameless.” Gibbons gave his lukewarm approval to the series’.

DC wasn’t done mining Watchmen for content. In 2017, they came out with Doomsday Clock, a sequel to the Moore/Gibbons series that introduced the Watchmen characters into the DC Universe. The series does leave options open for a sequel.

Whether or not DC comes out with more “original” content based on the Watchmen, the trade paperback will probably be sold by DC for the rest or Alan Moore’s and Dave Gibbons’ natural born lives. This case should be an example to all creators. Even if the contract appears creator friendly, it might not be.

Next time: A bunch of rock star artists think they’d be better going on their own than work for Marvel. Marvel thinks the rock stars are imminently replaceable. They are both right.