SPOILER WARNING: The plots of several current and past comic books, movies and TV shows will be discussed. Proceed at your own risk

Hey, did you see that show on Amazon Prime where Superman pretends to fight for truth, justice and the American way, but is really a self-centered sociopath who kills indiscriminately?

Oh, wait, that’s wasn’t Superman. That was a character Homelander in The Boys. My bad.

Okay, how about that cartoon on Amazon Prime where Superman doesn’t come to Earth to protect it but rather prepare it for invasion?

Sorry, that was Omni-Man in Invincible, not Superman. I should have known better. Omni-Man has a mustache for goodness sakes!

Well, how about that Netflix series where Superman has problems dealing a younger generation who doesn’t respect his code on not killing criminals or ruling the world?

D’oh! That’s the Utopian in Jupiter’s Legacy. My mistake.

All joking aside, we are now in peak pastiche season in the realms of comic book films, TV series and streaming. Thinly veiled copies of more famous heroes abound, and while this practice might be relatively new in film and TV adaptations, it is a long standing practice in the comics that inspired them. The question is, why are they so prevalent when creator credit is such a big issue.

American comic books were a derivative medium from the very start. The first modern comic books were repackaged newspaper comic strips. When the supply of reprintable comic strips started to dry up, publishers filled in the comic books with characters that resemble famous comic strips. Do you like Dick Tracy? Then give Slam Bradley a try. You a fan of Buck Rogers? Here’s Gary Concord, Ultra Man. Love The Shadow? Take a look at the Crimson Avenger. Follow Mandrake the Magician? Then follow Zatara. Some concepts varied greatly from the originals, others didn’t. Some of these characters stood the test of time, others had a very short life. But all were attempts to give readers what they wanted without being able to give them exactly what they wanted.

And then came Superman.

Superman wasn’t wholly original. Comic book historians have pointed out that Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were likely influenced by Philip Wylie’s 1930 novel Gladiator in creating the character. But still, Superman was unlike any other character in comics of the day. He was the first superhero as we know it, and spawned a litany of costumed heroes–and a number of imitators.

Superman wasn’t wholly original. Comic book historians have pointed out that Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were likely influenced by Philip Wylie’s 1930 novel Gladiator in creating the character. But still, Superman was unlike any other character in comics of the day. He was the first superhero as we know it, and spawned a litany of costumed heroes–and a number of imitators.

In an industry where nothing sold like success, there were a number of Superman clones springing up. DC Comics, mindful of the gold mine they had in the Man of Steel, got litigious when other companies characters hewed too close to Superman. They went after Fox Publications in 1939 over their character Wonder Man and after Fawcett in 1940 over their character Master Man and again in 1941 over their character Captain Marvel, a character that not only had a similar power set to Superman, but outsold him at the newsstands.

Wonder Man and Master Man appeared blandly similar to Superman, but at least Captain Marvel brought something different to the character. Yes, there are enough similarities in powers that it lost its lawsuit, but Captain Marvel had a more whimsical tone, a magical secret identity as a young Billy Batson, and a supporting cast that included a talking tiger.

Wonder Man and Master Man appeared blandly similar to Superman, but at least Captain Marvel brought something different to the character. Yes, there are enough similarities in powers that it lost its lawsuit, but Captain Marvel had a more whimsical tone, a magical secret identity as a young Billy Batson, and a supporting cast that included a talking tiger.

Making the character’s alter ego a child was a brilliant move by Fawcett. Kids made up a large part of the comic book readership in those days, and that move probably is why Captain Marvel sold so well at the newsstands. It also set a precedent–that creators can use an existing concept to create something valuable and entertaining.

Making the character’s alter ego a child was a brilliant move by Fawcett. Kids made up a large part of the comic book readership in those days, and that move probably is why Captain Marvel sold so well at the newsstands. It also set a precedent–that creators can use an existing concept to create something valuable and entertaining.

It would take a couple decades before the next round of pastiches came around. It was in 1969, and a new breed of comic book creator who grew up reading the comics of the late Golden Age and the early Silver Age. More often than not, they were a member of the raging counterculture movement of the time or close enough in age to respect it.

This generation was the first to push the boundaries of what comic books could be, tear down conventional norms and be bold enough to play a subversive joke on their employers.

It started at a party at Roy Thomas’ apartment. Thomas was the writer at the time of Marvel’s Avengers book and he was talking to Denny O’Neil, the writer on DC Comics’ Justice League of America and Mike Friedrich, a writer who had done fill-in issues for both companies. While they were talking, Friedrich got an idea–that the Avengers and Justice League should team-up. Thomas and O’Neil agreed immediately.

There was a major problem with that. Neither writer had the power at the time to make that kind of decision. Any team up would have to be approved at a higher level, and since there was a cold war going on between Marvel and DC at the time, any official team-up between the teams wasn’t going to happen. So Thomas and O’Neil had to get tricky.

Thomas’s side of the crossover first appeared on August 12, 1969 in Avengers #69, where he had a super team created by the villainous Grandmaster face the Avengers as part of a contest he was having with Kang. The team was called the Squadron Sinister and was composed of a Green Lantern double with the name of Doctor Spectrum, a Superman doppleganger called Hyperion, a Batman clone named Nighthawk, a Flash stand in called the Whizzer. They didn’t really behave like their DC Comics counter parts, but any comic fan could tell who they were based on.

Thomas’s side of the crossover first appeared on August 12, 1969 in Avengers #69, where he had a super team created by the villainous Grandmaster face the Avengers as part of a contest he was having with Kang. The team was called the Squadron Sinister and was composed of a Green Lantern double with the name of Doctor Spectrum, a Superman doppleganger called Hyperion, a Batman clone named Nighthawk, a Flash stand in called the Whizzer. They didn’t really behave like their DC Comics counter parts, but any comic fan could tell who they were based on.

Way more subtle was O’Neil’s part of the cross over the next month. Whether it was cold feet or editorial dictate, the Avengers didn’t get any direct doppelgangers in Justice League of America #75. Instead the Justice League fought evil duplicates of themselves. But each of their evil counterparts says or does something that references an Avenger counterpart. Evil Superman crows about being at “powerful as Thor.” Evil Batman uses a garbage can lid as a shield and throws much like Captain America slings his shield. Evil Atom mentions the ability to become a “giant, a veritable Goliath!,” a name that the Avengers Hawkeye adopted prior to this issue–Goliath.

Then there’s Hawkman. There was no bird themed hero on the Avengers at the time, so O’Neil compares him to Iron Man. As you can see above, it was a clumsy comparison at best.

Then there’s Hawkman. There was no bird themed hero on the Avengers at the time, so O’Neil compares him to Iron Man. As you can see above, it was a clumsy comparison at best.

The first “team-up” flew under the radar with each companies higher ups, so, two years later, the creators decided to do it again. Thomas was still writing the Avengers and in Avengers #85, he brought back the Squadron Sinister. Only this time, they were heroic versions of the characters called Squadron Supreme hailing from another reality. Thomas added four new members to the team based on four Justice Leaguers–Green Arrow (Hawkeye), Black Canary (Lady Lark), Hawkman (American Eagle) and Atom (Tom Thumb). The Avengers teamed with the Squadron to save the latter’s planet from destruction.

By this time, Friedrich was the writer on Justice League of America and for his part of the crossover, issue #87, he actually created some Avengers clones. Called The Champions of Angor, the quartet of heroes aped Thor (Wandjina), Quicksilver (Jack B. Quick), Scarlet Witch (Silver Sorceress) and Yellowjacket (Bluejay). The plot concerned itself with the teams mistakenly fighting each other, thinking the other was responsible for a killer robot let loose on both their worlds.

This time, Justice League editor Julius Schwartz did take notice and he didn’t find the shadow team-up funny at all. He commanded Friedrich never to pull the stunt again.

While there were no more coordinated team ups, the pastiches would return several times in the years that followed. Marvel most notably featured the Squadron Supreme in a 1985 miniseries. That series was one of the first examples of companies using pastiches to tell stories they could never tell with their original characters. In it, writer Mark Gruenwald uses the characters to examine what would happen if superheroes used their powers proactively to try and make the world a better place. In this case, that mission begins to infringe on individual freedoms, causing a rift in the superhero community.

While there were no more coordinated team ups, the pastiches would return several times in the years that followed. Marvel most notably featured the Squadron Supreme in a 1985 miniseries. That series was one of the first examples of companies using pastiches to tell stories they could never tell with their original characters. In it, writer Mark Gruenwald uses the characters to examine what would happen if superheroes used their powers proactively to try and make the world a better place. In this case, that mission begins to infringe on individual freedoms, causing a rift in the superhero community.

DC would use the Champions of Angor characters again, but to a lesser extent. They reappeared in the 1987 volume of the Justice League.

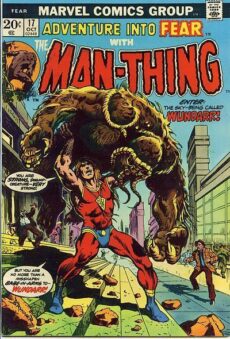

Our next notable pastiche comes from Marvel and first appeared in the 17th issue of the unlikely series Adventure into Fear.

Stop me when this starts to sound familiar. A scientist on the planet Dakkam discovers that the planet is about to be destroyed. The planet’s leadership refuses to heed his warnings, so he is left with only one option–send his infant son Wundarr to Earth and to safety. As his ship arrives on Earth, it is noticed by an older couple, who notices the flying saucer crash in a remote part of Florida.

Stop me when this starts to sound familiar. A scientist on the planet Dakkam discovers that the planet is about to be destroyed. The planet’s leadership refuses to heed his warnings, so he is left with only one option–send his infant son Wundarr to Earth and to safety. As his ship arrives on Earth, it is noticed by an older couple, who notices the flying saucer crash in a remote part of Florida.

Even people who have never read a comic book in their lives will recognize that as Superman’s origin.But in case anybody wasn’t sure, Wundaar came out wearing Surpeman’s colors–blue unitard, red shorts, and red boots.

However, this version was written by the master of comic book satire, Steve Gerber, so the pastiche veers off pretty quickly–starting with the origin. In this one, the older couple are not like the Kents. “Paw! You stay right here!,” the Ma Kent doppelganger says. “It could be martians–or communists–! You could get your fool self ray-gunned t’death!”

So the spaceship sits in a Florida swamp for two decades until it is discovered by Man-Thing. Wundarr comes out of the ship a full-grown man, but with the mind of a child. His path to discovery lead him into a battle with Man-Thing, who he mistaken believes is his mother. Yes, that is right. His mother.

The character would move to Marvel Two-In-One with Gerber, becoming a supporting character of The Thing in the comic. His intelligence progressed to that of a toddler (“Wanna candee, Unca Ben!,” he says to The Thing in MTIO #4. “Candee!”). This might have been Gerber trying to make a point of how infantile the DC Comics stories were. Or is could have been a way to differential Wundarr from Superman.

Because DC Comics took notice of the similarities. Threats of lawsuits were thrown about, and Stan Lee was seriously considering firing Gerber as a peace offering. Eventually DC backed down as long as Marvel made changes to the character. By Wundarr’s third appearance, his costume was changed to a solid blue number. His powers were explained as not being rocketed to earth but being exposed to cosmic rays. Within three years, Wundarr became Aquarian, less a Superman pastiche and more a Jesus Christ metaphor. Which, considering that Superman has become a Christ metaphor himself in the years that followed, it made Aquarian an even bigger Superman pastiche than he had been before.

Because DC Comics took notice of the similarities. Threats of lawsuits were thrown about, and Stan Lee was seriously considering firing Gerber as a peace offering. Eventually DC backed down as long as Marvel made changes to the character. By Wundarr’s third appearance, his costume was changed to a solid blue number. His powers were explained as not being rocketed to earth but being exposed to cosmic rays. Within three years, Wundarr became Aquarian, less a Superman pastiche and more a Jesus Christ metaphor. Which, considering that Superman has become a Christ metaphor himself in the years that followed, it made Aquarian an even bigger Superman pastiche than he had been before.

Gerber would not be a stranger to the pastiche, including one of Howard the Duck in his Destroyer Duck series, which we talked about here.

Roy Thomas was behind another shadow inter-company crossover with DC Comics in 1976. Both Marvel and DC had series with teams tie into the World War II era. Marvel had The Invaders, which was written by Thomas and featured Marvel’s Golden Age heroes–Captain America and Bucky, Human Torch and Toro, Sub-Mariner, teaming up with a new Thomas creation, Spitfire. DC had Freedom Fighters, a team composed of Golden Age characters DC had acquired when they bought out their former rival Quality Comics. The team was composed of Uncle Sam, Doll Man, Black Condor, The Ray, Human Bomb, and Phantom Lady. Their adventures were written by Bob Rozakis and often took place on an alternate world where the Nazis won World War II. Thomas, being a Golden Age fan and scholar, decided to have the two teams meet.

The Invaders were first up in November of 1976 when in issue #14 the met up with a team called “The Crusaders.” The Crusaders were a team based in Europe consisting of The Spirit of ’76 (based on the Freedom Fighters’ Uncle Sam), Captain Wings (Black Condor), Dyna-Mite (Doll Man), Ghost Girl (Phantom Lady), Thunder Fist (Human Bomb), and Tommy Lightning (The Ray). The team works under the watchful eye of a British spy named Alfie, and after they capture a crew of a German plane, they become responsible for guarding the King of England. This is just what Alfie wants because unbeknownst to the team, Alfie is a double agent and plans to kill the King. It takes the combined might of both the Invaders and the Crusaders to foil the plot.

The Invaders were first up in November of 1976 when in issue #14 the met up with a team called “The Crusaders.” The Crusaders were a team based in Europe consisting of The Spirit of ’76 (based on the Freedom Fighters’ Uncle Sam), Captain Wings (Black Condor), Dyna-Mite (Doll Man), Ghost Girl (Phantom Lady), Thunder Fist (Human Bomb), and Tommy Lightning (The Ray). The team works under the watchful eye of a British spy named Alfie, and after they capture a crew of a German plane, they become responsible for guarding the King of England. This is just what Alfie wants because unbeknownst to the team, Alfie is a double agent and plans to kill the King. It takes the combined might of both the Invaders and the Crusaders to foil the plot.

In creating the ersatz Freedom Fighters, Roy Thomas played it subtle. If you knew what you were looking for, you can tell which Crusader was based on which Freedom Fighter. Rozakis was a whole lot more direct with his copies of the Invaders

Teased the next month in Freedom Fighters #7, Rozakis’ team of pastiches, also called The Crusaders, were a virtual carbon copy of their Marvel counterparts. The team was composed of Americommando and Rusty (Captain America and Bucky), Fireball and Sparky (Human Torch and Toro) and Barracuda (Sub Mariner). As you can see to the right, The characters have the same essential design as the heroes they are supposed to be mimicking. Only a color scheme change here and there to stave off litigation

Teased the next month in Freedom Fighters #7, Rozakis’ team of pastiches, also called The Crusaders, were a virtual carbon copy of their Marvel counterparts. The team was composed of Americommando and Rusty (Captain America and Bucky), Fireball and Sparky (Human Torch and Toro) and Barracuda (Sub Mariner). As you can see to the right, The characters have the same essential design as the heroes they are supposed to be mimicking. Only a color scheme change here and there to stave off litigation

The story has The Crusaders working with law enforcement to try and capture the Freedom Fighters, who have been mistakenly accused with working with the villainous Silver Ghost. In reality, the Americommando was Silver Ghost, and the whole thing was a ruse to get his hands on the heroes. The rest of the team were just four comic fans he found at a comic book convention and gave powers to. The fans were named Lennie, Arch, Marvin and Roy, a wink towards fans turned creators Len Wein, Archie Goodwin, Marv Wolfman, and Roy Thomas.

Why didn’t Marvel sue for such a blatant rip off? Well, maybe it was because it was because Marvel and DC were starting to do official crossovers with a big meeting between Superman and Spider-Man that very year.

One of the most famous pastiches of all time almost wasn’t a pastiche at all. It started as a project that would have been titled, “Who Killed the Peacemaker?”

It was an example of perfect timing, In 1983, DC Comics made an arrangement with Charlton Comics to buy their superhero characters. Around the same time, British writer Alan Moore, who had just started working for DC Comics on the Saga of Swamp Thing, was looking for another property to revamp. But this time he wanted to do more serious deconstruction of the superhero genre, like he did in Britain with Marvelman (itself a pastiche character after its publisher lost the rights to Captain Marvel as a result to the DC/Fawcett lawsuit of the 1940s). Originally, he thought DC would be obtaining Archie Comic’s superhero characters and built an unsolicited proposal around that. When he found out that it was the Charlton characters, he adjusted the proposal accordingly.

It was an example of perfect timing, In 1983, DC Comics made an arrangement with Charlton Comics to buy their superhero characters. Around the same time, British writer Alan Moore, who had just started working for DC Comics on the Saga of Swamp Thing, was looking for another property to revamp. But this time he wanted to do more serious deconstruction of the superhero genre, like he did in Britain with Marvelman (itself a pastiche character after its publisher lost the rights to Captain Marvel as a result to the DC/Fawcett lawsuit of the 1940s). Originally, he thought DC would be obtaining Archie Comic’s superhero characters and built an unsolicited proposal around that. When he found out that it was the Charlton characters, he adjusted the proposal accordingly.

DC Managing Editor Dick Giordano, an ex-Charlton Comics employee, liked the treatment–just not for the Charlton characters. Moore’s proposed series would leave the Charlton all but unusable to DC, so Giordano advised Moore to use new characters in his series. Moore created new characters for the series but didn’t stray too far from the original inspiration. The bug-themed Blue Beetle became the bird-themed Nite Owl. The nuclear powered Captain Atom became the nuclear powered Dr. Manhattan. The trench coat and fedora wearing Question became the trench coat and fedora wearing Rorschach. And, so, the Watchmen were born.

Being forced to use pastiches of the Charlton characters instead of the characters themselves was a godsend for Moore. It allowed him a freedom that he wouldn’t have had if he was working on licensed characters. And he used that freedom to create one of the best comic book series in the history of comics.

It also started a shift in how pastiches were being used. They weren’t used as often for inside jokes or subtle, unapproved crossovers. They were instead used for examining and deconstructing the heroes they were copying.

There Rich Veitch’s Brat Pack. a look at not only the more seedy implications of the child sidekick trend in comics but also an indictment of how commercialization hampers creativity. Then you have Veitch and other creators joining Alan Moore in his 1963 project, a parody of early Marvel Comics that acted as a commentary by contrast on the grim and gritty comics of the 1990s and also how the business back then wasn’t always a cheery as “Bullpen Bulletins” made it seem. And you had Mark Millar, who made a cottage industry out of doing pastiches, offering skewered takes on James Bond (The Secret Service), Flash Gordon (Starlight), and Batman (Nemesis) in addition to the aforementioned Jupiter’s Legacy.

These pastiches allowed creators to be free of corporate restraints and tell stories using these archetypes that would never fly in mainstream comics. DC might show what would happen if Superman became drunk with power in their Injustice series and video games, their are lines they will not have him cross. The Boys and Invincible have no problem crossing those lines in examining their concepts.

Just as pastiches in comic books became a way to deconstruct the dominant superhero trope in shocking and daring ways, so do the above adaptations serve the similar purpose for the incredibly popular live-action version of the superheroes. The Snyderverse might tease what would happen if Henry Cavill’s Superman became evil, but Anthony Starr’s Homelander in The Boys shows us better how it really would work out.

You might ask, how can these people get away with making comics and TV shows out of pastiches of established heroes.Well, that is most likely covered under the “fair use” doctrine of copyright law. The doctrine allows the use of copyrighted materials without getting the permission of the copyright holder. Typically, this is what allows film reviewers to use descriptions of films in their reviews. But it also applied to derivative works such as pastiches, as long as you call them parodies.

To qualify as fair use, the work within four guidelines:

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes: That the new work has to be transformative of the copyrighted work, that it needs to serve a purpose on its own different from the original work.

- The nature of the copyrighted work: Whether the copyrighted work is important enough to be copyrighted to parodied. Wikipedia used the Zapruder film from the Kennedy assassination as an example. Time owned the copyright to the film, but when Time sued a textbook publisher who used frames from the film in a book, the courts ruled against Time saying that the images being free of copyright protection was in the public interest.

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole: If you wanted to put one panel from a Silver Age Superman story to show how much of a dick he is, that’s fair use. If you reprint an entire story, that’s not.

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work: Basically, if your parody costs the copyright holders money, either by employing a concept they were going to employ in the future or take away business from the concept, then it is not fair use. If your parody points out how awful a concept is, and that costs the copyright holder money, then that is fair use.

Most pastiches fall within the guidelines of fair use, so that’s why we can have The Boys with the Superman character masturbating off a skyscraper.

Next Time: Alan Moore holds a lot of grudges in the comic book industry. We’ll talk about the rights issues over Watchmen that cause one of them.