You might not know of the name Steve Gerber. He hasn’t reached the echelon of real world fame that Stan Lee, Neil Gaiman or Alan Moore has. But he was one of the more inventive writers in comics. And for a brief moment in the 1970’s, he was able to catch lightning in a bottle and created a cultural phenomenon that transcended comic books.

Gerber was working as a copyrighter in 1972 when he desperately need a change. He contacted his friend Roy Thomas, who offered him a job as an assistant editor for Marvel Comics. Unfortunately, that position wasn’t fit for him. Instead, he became a writer, working on books such as Daredevil, Sub-Mariner, Man-Thing and Defenders.

Gerber’s writing set him apart from the field of other comic book writers. He was anything but conventional. His style mixed cutting social satire with boundary pushing humor and inventiveness. He would tackle topic such as racism, violence, greed and sexism but also write himself into a comic to let readers know he leaving the title or create a subplot where a pink suit wearing elf would shoot complete strangers with a gun without any explanation or closure.

In 1973, Gerber would create a character who would play into his strengths as a writer. Howard the Duck first appeared in the Man-Thing strip in Adventures into Fear #19. He would briefly become a supporting character for the swamp monster before editor Roy Thomas, who thought the concept was too wacky for the book told Gerber to get rid of him.

In 1973, Gerber would create a character who would play into his strengths as a writer. Howard the Duck first appeared in the Man-Thing strip in Adventures into Fear #19. He would briefly become a supporting character for the swamp monster before editor Roy Thomas, who thought the concept was too wacky for the book told Gerber to get rid of him.

However, fans didn’t want Marvel to get rid of Howard. Letter started pouring from readers, castigating the company for killing off their duck. One fan even sent in the carcass of a dead duck that was his meal into Marvel’s offices. Fans also accosted Roy Thomas and Stan Lee at public appearances in regards to the character. This led Marvel to give Howard a back-up strip in a number of comics before finally getting a comic book of his own.

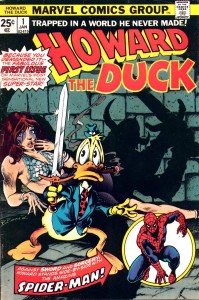

Howard the Duck #1 hit stands in October of 1975 and it was unlike anything comic fans had ever seen. It was born in an era where satire was in full bloom, a world that was welcoming Saturday Night Live and Blazing Saddles and Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman into the pop culture zeitgeist.

The comic book poked fun on popular comic book trends of the day: barbarian-themed sword and sorcery, martial arts, gothic horror, and satanic scares. But Gerber would used his attacks of these tropes to comment on youth violence, the degradation of women and backroom political power jockeying. Nothing was sacred. Everything could be the butt of a joke.

The comic book poked fun on popular comic book trends of the day: barbarian-themed sword and sorcery, martial arts, gothic horror, and satanic scares. But Gerber would used his attacks of these tropes to comment on youth violence, the degradation of women and backroom political power jockeying. Nothing was sacred. Everything could be the butt of a joke.

The title was an instant sensation. The first issue was selling on the back issue market for $10 only six months after it was released, a 4000% return on its original $.25 investment. Whenever mainstream media wrote about comics, it mentioned Howard the Duck. Disney took notice and contacted Marvel over what they saw as Howard’s similarities to Donald. Disney made Marvel put pants on Howard and make minor changes to his design. The design changes stayed. The pants did not. And most impressive of all, Howard got a number of write-in votes in the 1976 Presidential Election, certainly spawning from a promotional blitz that Marvel undertook from a story line in the comics where Howard was drafted to run for president.

Since nothing sells like success, Marvel allowed Howard to be adapted into comic strip form. Written by Gerber and drawn at first by Howard’s comic artist Gene Colan, the strip hit newspapers on June 6, 1977. In October of that year, Marvel made Gerber an exclusive employee and gave him more control over Howard. Things were looking up for Gerber and Howard. It wouldn’t last.

Steve Gerber was often late, and often missed deadlines. In comic books, this was bad but not a deal killer. Marvel moved to accommodate Gerber’s issues with lateness. They moved Howard the Duck to a bimonthly schedule and took him off the writing duties of Captain America to easy his work load. But in the world of newspaper comic strips, missing deadlines is deadly. Syndicates usually get their strips in 10 weeks ahead of publication. Gerber was delivering his strips the Friday before the Monday they ran. Newspapers were complaining about the lateness and were threatening to drop the strip. The syndicate gave Marvel an ultimatum: fire and replace Gerber or there wouldn’t be a Howard comic strip.

Marvel acquiesced. In March of 1978, Stan Lee phoned Gerber to tell him he was fired off of the Howard the Duck comic strip. Gerber’s lawyer requested a former letter of termination, and he got one on March 28, 1978.

Gerber did not take his removal from the Howard the Duck strip well. On April 5, 1978, he sent a telegram to Marvel, reprinted by R.S. Martin in his extensive article detailing the Gerber lawsuit (an article which aided in the writing of this one, and goes into far more detail, it is worth a look):

Please regard this as a formal notice that I, and not Marvel, am and shall be the exclusive owner of the comic character “Howard the Duck” and of all other characters, plots, themes, and settings created by me or under my authority which have been included in the comic strip, as well as the copyright(s) therein and thereto and all other incidental and allied rights, including tradenames, trademarks, etc., and any use after April 27, 1978 by Marvel or under its authority of any of said rights without my written consent thereto.

Furthermore, Gerber threatened to sue Marvel if they infringed on his right pertaining to the character. This caused Marvel to terminate Gerber’s comic book rwriting and editing contract, essentially firing him from Marvel.

Gerber would hold off on his threats of sued for the rights to Howard the Duck for several years while he began working in animation, creating Thundarr the Barbarian and working on Plastic Man, G.I. Joe and Dungeons and Dragons. As for Howard, he began the slow slide into irrelevance without Gerber at the helm. The comic book series only lasted two more issues after Gerber’s departure. It moved into a black and white magazine format that only lasted nine issues before being cancelled. The Howard comics strip would also come to an end, lasting only until October 1978.

Gerber would hold off on his threats of sued for the rights to Howard the Duck for several years while he began working in animation, creating Thundarr the Barbarian and working on Plastic Man, G.I. Joe and Dungeons and Dragons. As for Howard, he began the slow slide into irrelevance without Gerber at the helm. The comic book series only lasted two more issues after Gerber’s departure. It moved into a black and white magazine format that only lasted nine issues before being cancelled. The Howard comics strip would also come to an end, lasting only until October 1978.

However, Howard still caught the eye of people who wanted to adapt the character into other mediums. Marvel licensed Howard to Selluloid Productions to adapt the character into radio, TV and films. A pilot for a radio serial was made featuring a young Jim Belushi as the voice of Howard. Selluloid also held a one-year option to make a Howard film, which elapsed, sparing them the blame for Howard the Duck film we got.

The deal got the attention of Gerber, who still believed he held the rights to Howard the Duck. On June 30, 1980, Gerber’s lawyer sent a cease and desist order to Marvel to stop the licensing deal. Marvel ignored this, leading Gerber to file suit for the rights to Howard on August 29, 1980.

The Gerber lawsuit was a cause célèbre in the comic book community, who saw it as a landmark case in determining creator rights under the new copyright law. As such, popular creators of the day rallied around Gerber to help pay his legal bills. A group of artists got together to create the F.O.O.G. (Friends of Old Gerber) portfolio. Artists such as Dave Sim, Michael Wm. Kaluta, Charles Vess, Wendi Pini and Bernie Wrightson created plates that would be sold as a set with the proceeds going to Gerber’s legal battle.

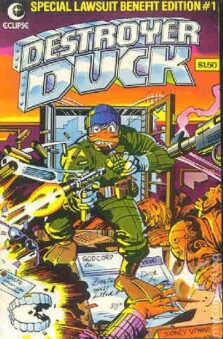

But the most famous benefit item was the Destroyer Duck comic book.  In it, Gerber joined with the legendary Jack Kirby, who was also working in animation at the time (he did design work on Thundarr the Barbarian) and was also fighting with Marvel over the return of his original artwork, to create the comic’s lead character.

In it, Gerber joined with the legendary Jack Kirby, who was also working in animation at the time (he did design work on Thundarr the Barbarian) and was also fighting with Marvel over the return of his original artwork, to create the comic’s lead character.

Duke Duck was a rough and tumble duck living in an anthropomorphic world. A friend of his, called “The Little Guy”, is duck-napped and taken to an alternate reality where he is forced to perform for the benefit of a conglomerate called Godcorp. Godcorp uses The Little Guy, chews him up and spits him out when they are done. After he finally makes it home to his own dimension to die in Duke’s arms, Duke swears vengeance on Godcorp, and travels to the alternate dimension to enact it.

The series is sarcastic, satiric Gerber at his finest. Not only does it act as a commentary on his own situation (The Little Guy is meant to represent Howard the Duck, but also represents Gerber himself) but also takes aim at the popular trends of the day like the Pac-Man craze and, of all things, Strawberry Shortcake.

The comic and the portfolio did well, but was only able to pay 20% of Gerber’s legal bills, which cumulatively added up to over $140,000 at the time. This is a main reason why the fight for creator rights don’t often work out in favor for the creator. Facing a corporation with a team of lawyers on their beck and call and with a war chest that numbers in the millions, they can simply win their case by attrition, bleeding the creator dry until he can no longer afford to pay for the lawsuit.

This is what happened to Gerber. Gerber and Marvel settled the lawsuit on September 24, 1982. Gerber received a modicum of editorial control over the character, the promise of higher page rates should he ever write Howard again, and would get a financial consideration of any profits from TV shows and movies the character (essentially, he was added to Marvel’s profit participation program). In return. Gerber gave up all rights to the character, agreeing that Howard was created as “work-for-hire.”

Next time: We look into how determining a creator of a character isn’t as easy as it seems in a collaborative medium such as comics.