It started with The Hollywood Reporter. Then came The Guardian. Stories about comic book creators not getting what they think is their fair shake from their creation being featured in billion dollar films are popping up all over the media.

It started with The Hollywood Reporter. Then came The Guardian. Stories about comic book creators not getting what they think is their fair shake from their creation being featured in billion dollar films are popping up all over the media.

I already wrote about this topic a little while back but it is a complex topic that calls for a more in depth examination. This article is the start of a series that will shine a light on the way comic book creators are rewarded for their creations. We’ll try to look at all sides of the issue. We’ll look through the shadowy mist of history to show that writers and artists not getting paid for the film contributions has a long-standing precedent in comic books. We’ll show the struggle for creator right’s throughout the decades. We’ll show what effect comic characters being adapted into other media had on creators getting their due. And we are going to start it off this week at the beginning–with the early days of comic books.

Dawn of a New Medium

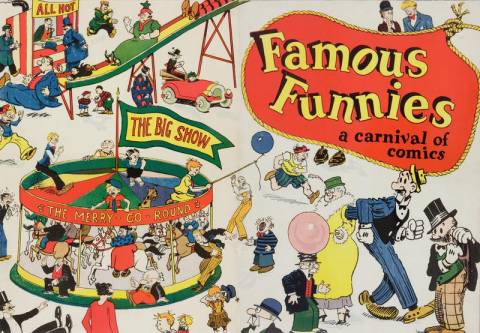

You can say that the comic book dates back to the 1800’s, but most comic book historians look to Famous Funnies: A Carnival of Comics in 1933 as the first modern comic book. The comic reprints popular newspaper comic strips of the day such as Mutt and Jeff and Joe Palooka and proved to be insanely popular. Famous Funnies spawned numerous imitators, each reprinting popular comic strips. When the supply of available comic strips to reprint went away, the comic book companies started to provide original stories similar to the popular strips of the day. Many of the new characters and stories had the look and feel of the popular established comic strips.

You can say that the comic book dates back to the 1800’s, but most comic book historians look to Famous Funnies: A Carnival of Comics in 1933 as the first modern comic book. The comic reprints popular newspaper comic strips of the day such as Mutt and Jeff and Joe Palooka and proved to be insanely popular. Famous Funnies spawned numerous imitators, each reprinting popular comic strips. When the supply of available comic strips to reprint went away, the comic book companies started to provide original stories similar to the popular strips of the day. Many of the new characters and stories had the look and feel of the popular established comic strips.

This was the way it was until 1938, when DC Comics published the first Superman story in Action Comics #1. Superman was unlike any thing that appeared in comic books up to that point. He dressed like a circus strong man. He could lift cars above his head. Bullets bounced off him. He was the world’s first costumed superhero, became instantly popular, spawned legions of imitators and changed the face of medium forever.

Superman also made billions of dollars for DC Comics and its various corporate parents over his 80 years of existence. His creators, however, were consigned to abject poverty. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster are the poster children for comic book creators not getting the financial benefits they deserve. Every article written about comic creators being cheated out of money they have due seems legally obligated to mention the pair. The two recent articles I refer to above make a point of mentioning them.

People today might be puzzled why Siegel and Shuster signed away a multi-billion dollar piece of intellectual property for nothing. Looking at the historical landscape the deal was made in might help people understand the decision more. And what we learn can be applied to other creators from the Golden Age of Comics and will set the stage for the way comic book creators will be treated for decades to come.

Case Study: Superman

Siegel and Shuster received $130 on March 1, 1938 for writing and drawing the first Superman story, but they actually signed away the rights to the character for free on the very same day. They signed a contract that said that by accepting payment for writing and drawing any story they did for DC, they were agreeing to sell the rights to that character or characters to DC. This included not only Superman but other characters the pair created, such as Slam Bradley.

Siegel and Shuster received $130 on March 1, 1938 for writing and drawing the first Superman story, but they actually signed away the rights to the character for free on the very same day. They signed a contract that said that by accepting payment for writing and drawing any story they did for DC, they were agreeing to sell the rights to that character or characters to DC. This included not only Superman but other characters the pair created, such as Slam Bradley.

The duo would eventually come to regret that decision, but there is plenty of evidence that at the time it could be considered a prudent decision. Allow me to explain.

The Great Depression was still going on.

In 1938, the country was still reeling from the Stock Market Crash of 1929. Recovery was was hampered by a recession that hit in 1937. The unemployment rate would hit 19%, the highest it had been in three years and highest it would be since. The government was starting the New Deal policy of unemployment benefits, and expected 12 million Americans to sign up. So, it was a perilous time economically in the country. That contract Siegel and Shuster signed came with the promise of steady work. It came with a regular check that could be used to help their families out in a time of need.

Confidence in Superman was low.

There was not a bidding war for Superman. Actually, it was the opposite. Siegel and Shuster had been trying to sell Superman to newspaper syndicators since 1933. They continually tweaked the concept, and Siegel even went to other artists other than Shuster to try to get picked up by syndicators to no avail. DC Comics was the only company at the time willing to take a chance on the concept.Even then, publisher Harry Donenfeld was so offended by the character appearing on Action #1 cover that he banned the character from ever appearing on the cover again. That only changed once the popularity of the character grew. By issue #22, Superman would take his rightful place on the cover of every issue.

There was not a bidding war for Superman. Actually, it was the opposite. Siegel and Shuster had been trying to sell Superman to newspaper syndicators since 1933. They continually tweaked the concept, and Siegel even went to other artists other than Shuster to try to get picked up by syndicators to no avail. DC Comics was the only company at the time willing to take a chance on the concept.Even then, publisher Harry Donenfeld was so offended by the character appearing on Action #1 cover that he banned the character from ever appearing on the cover again. That only changed once the popularity of the character grew. By issue #22, Superman would take his rightful place on the cover of every issue.

So, it wasn’t a case of Siegel and Shuster knowing they were selling a surefire hit to DC. It more a case of them finally getting the character published.

The $130 price wasn’t as low as it seemed and it wasn’t all that the pair got.

Today, that $130 amount seems punitively small for what Superman earned. Even adjusted for inflation, the $2,505 is a paltry sum in response to the billions the character ended up being worth. And if they were only getting $130 per month for their work on the title, that would have put both men way below the yearly average income in 1938 of $1,731 per year. But as you can see itemized in the check above, the pair did other features for DC Comics adding up to a total check of $412. Considering these were monthly features they were doing, you can assume that they were getting that same amount every month. If they were splitting the payment equally, with out any raise in pay rates, that means each man was making $2,472 a year, more than $700 more than the average yearly income. Again, this would be a pittance compared to what DC Comics was making off of their work, but money that they wouldn’t want to lose when people were selling apples on the street to survive.

Siegel and Shuster were only 23 when they sold Superman.

Age and maturity do not always go hand in hand. I know some teenagers who carry themselves with more maturity than some adults. I also know some adults who act more immature than little kids on a playground. But being 23 at the time they signed away the rights to Superman, you have to believe that Siegel and Shuster didn’t know what they didn’t know. They went into the agreement with DC Comics in the belief that they would have a job writing and drawing Superman for the rest of their lives. They had no idea exactly what they were signing away. That they were considered replaceable.

They also entered into the agreement flush with the realization that they were able to provide for their parents at a very young age. Many of the founding fathers of superhero comics got their start in comics even younger than Siegel and Shuster did. If you read interview with these creators, you get the sense of pride in the fact that they were able to help their family out when they needed it the most. That might have clouded the pair’s judgement too, making them want to support their family now instead of being set for life.

The Past In Prologue

With the case of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, you can see the start of the road the comic book industry paved and forces their creators to travel on. Again and again in this series of articles, you’ll see comic companies renege on their agreements. You’ll see them shut the people making the comics off from the full rewards of their efforts. You’ll see artist fight for their rights with various levels of success. And it all began here, with the earliest creators of the golden age.

Next time:

We take a break from the chicanery of comic book companies screwing over creators to show you that other creators can also screw over their fellow creators, with the most famous case of one creator taking full credit for one of the most famous comic book characters of all time, leaving his co-creators to flounder.