Recently, The Hollywood Reporter ran a story titled “Marvel and DC’s “Shut-Up Money”: Comic Creators Go Public Over Pay,” and it begin with a rehashing of comic book writer Ed Brubaker’s April 12 appearance on the Fatman Beyond podcast. On it, Brubaker expresses his disdain about not receiving any money for the Winter Soldier’s appearance in Captain America: Civil War and The Falcon and the Winter Soldier. This led to his widely circulated quote that the writer of the Hollywood Reporter article, Aaron Couch, decided to share:

“I have made more on SAG residuals than I have made on creating the character,” Brubaker told Kevin Smith and Marc Bernardin on the Fatman Beyond podcast, referencing his cameo in Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014).

I only have one problem with that quote. Ed Brubaker didn’t create Winter Soldier. Not really. At least, not by himself.

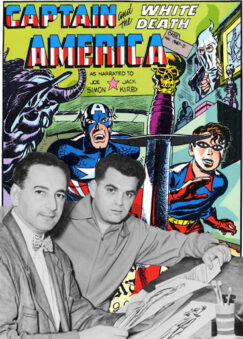

As any Marvel fan can tell you, the Winter Soldier is James Buchanan “Bucky” Barnes. In the films, he is portrayed as Steve Rogers’ friend from growing up in Brooklyn. In the comics, he was Captain America’s war-time teen side kick. He made his first appearance the same time Cap did–in 1941’s Captain America #1 He, like Cap was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby.

As any Marvel fan can tell you, the Winter Soldier is James Buchanan “Bucky” Barnes. In the films, he is portrayed as Steve Rogers’ friend from growing up in Brooklyn. In the comics, he was Captain America’s war-time teen side kick. He made his first appearance the same time Cap did–in 1941’s Captain America #1 He, like Cap was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby.

When Captain America was revived in 1964’s Avengers #4, Bucky was revealed to have apparently been killed at the end of World War II. That part of his backstory was added by Stan Lee and the character’s co-creator Jack Kirby.

The character lay dormant for over 40 years–barring the occasional flashback – before Brubaker revived him in 2005’s Captain America #1. But he didn’t bring him back alone. The design and look of the character was done by series artist Steve Epting. And a continuity change this big was probably not done without the input and approval of the book’s editors, Tom Brevoort, Andy Schmidt, Nicole Wiley and Molly Lazer. It’s also likely editor-in-chief at the time Joe Quesada had some say on how Bucky was brought back.

In other words, the art of character creation is a complex and debatable issue in comics. But you’d never know that from reading Couch’s poorly written article.

You don’t have to wait long to find out the sloppy, lazy way Couch will be delivering his article. Because in the second paragraph, Couch casually lets loose with this “fact”:

In May, Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose run on Black Panther comics helped the $1.2 billion- grossing Chadwick Boseman film get greenlit, backed Brubaker in an interview with Polygon…

Personally, I would like to see Couch’s math on this. I would like see how Coates’ run on the title, which was first announced in September of 2015 and began in April of 2016, had any effect on Black Panther being green lit, which happened on October 2014. Was time travel involved? In addition to being a great writer, does Coates have reality warping abilities? Or did Couch misread the Polygon interview, thought Coates was complaining about not getting paid for getting the film made and was too lazy to do the due diligence to see if it was factually correct. All three seem unlikely to have happen in this day and age, but the last one seems most likely of the three.

But giving Ta-Nehisi Coates undue credit for one of Marvel Studios highest grossing films or misspelling Jeph Loeb’s name is bad, but not the worst error Couch made. In an article all about giving comic creators their due, Couch has no qualms leaving creators unnamed. Epting is not listed as co-creating the Winter Soldier, even though Brubaker gives him such credit in the podcast Couch quotes from. And Couch only lists Todd McFarlane as co-creator of Venom, not anybody else in the process.

It is funny that Couch would choose Venom as a character to discuss comic creator credit because it was part of a skirmish in the war between writers and artists that raged in the fan press in the early 1990’s. Starting in 1992, around the time Image Comics started, with Erik Larsen’s infamous “Name Withheld” letter in Comics Buyer’s Guide where he called comic writers hacks that recycle their stories and that comic artists don’t really need them, an at times petty and vicious civil war erupted between both sides.

It is funny that Couch would choose Venom as a character to discuss comic creator credit because it was part of a skirmish in the war between writers and artists that raged in the fan press in the early 1990’s. Starting in 1992, around the time Image Comics started, with Erik Larsen’s infamous “Name Withheld” letter in Comics Buyer’s Guide where he called comic writers hacks that recycle their stories and that comic artists don’t really need them, an at times petty and vicious civil war erupted between both sides.

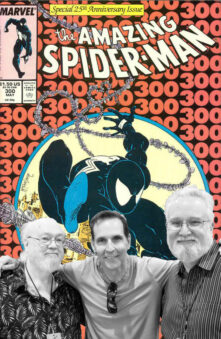

Into this climate comes Wizard Magazine in 1993. In their 17th issue, they listed David Michelinie as “co-creator” of Venom with Todd McFarlane in the pages of Amazing Spider-Man #300. Michelinie wrote into the magazine a few issues later, saying that the creation of Venom was all but wrapped up by the time McFarlane joined the title with issue #298, a fact backed up by writer Peter David in the pages of Comics Buyer’s Guide in is “But I Digress ” column. Erik Larsen responded in the pages of Wizard #23, rehashing his “writers are recycling hacks” logic and McFarlane deserves most of the credit because his art is what made the character commercial. McFarlane, to his credit, backed up Michelinie’s version of the creation timeline, but stated he was responsible for the character’s design.

So, it’s not easy determining credit when you have only two people to choose from. However, the creation of Venom is far more convoluted than that. Let’s map it together.

You can argue that you wouldn’t have had a Venom without Spider-Man. Spider-Man was created by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko. Jack Kirby, who was asked to supply a pitch for Spider-Man that was rejected would later claim he created the character, could also be included. I wouldn’t, but feel free to add him if you choose.

I’m not going to list every creator that worked on Spider-Man from its creation to issue #300. But you can argue that they should also get credit for the creation of Venom for what they added to the Spider-Man mythos.

But all of that is prologue. The nitty gritty of the creation of Venom started with a black suit Spider-Man. The suit made its first appearance in 1984’s Amazing Spider-Man #252. That issue was written by Roger Stern and Tom DeFalco with art by Ron Frenz and Brett Breeding and edited by Danny Fingeroth. That issue featured Spidey returning from the Secret Wars that he was absconded to in the previous issue.

While the Secret Wars only happened for the heroes between issues of their regular series, it played out over a year in the pages of the Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars miniseries. Fans would have to wait seven months to find out how Spider-Man got that costume. In the 8th issue of that miniseries, we see that Spider-Man enter a room that supposedly had a machine that could repair his battle torn costume. He puts his hand under a machine and a black ball of goo comes out. The ball melts in Spidey’s hands and spreads over his body until he has a new costume. The issue was written by then Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter with art by Mike Zeck and John Beatty. DeFalco was the editor of the series.

While the Secret Wars only happened for the heroes between issues of their regular series, it played out over a year in the pages of the Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars miniseries. Fans would have to wait seven months to find out how Spider-Man got that costume. In the 8th issue of that miniseries, we see that Spider-Man enter a room that supposedly had a machine that could repair his battle torn costume. He puts his hand under a machine and a black ball of goo comes out. The ball melts in Spidey’s hands and spreads over his body until he has a new costume. The issue was written by then Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter with art by Mike Zeck and John Beatty. DeFalco was the editor of the series.

By that time, fans already knew what the costume was. The month prior, in Amazing Spider-Man #258, Spidey visits Reed Richards to get the suit examined. Richards discovers that the suit is an alien symbiote that had attached itself to Spider-man. It also determined that the symbiote was vulnerable to loud sounds and sonics . Richards manages to separate the suit from Spidey and imprison it and the symbiote begins to hate Peter Parker because of it. That issue was written by DeFalco with art by Frenz and Josef Rubinstein and was edited by Fingeroth.

John Byrne has claimed that he came up with the idea of an alien, self-healing suit as an unused concept for Iron Fist’s costume and gave it to Roger Stern to use. Take that as you will.

Eventually,the symbiote escapes and reattaches itself to Peter. After an struggling to remove the symbiote, Spider-Man goes to a church bell tower and the sounds of a bell ringing seemingly destroys the symbiote. This all took place in Web of Spider-Man #1, written by Louise Simonson with art by Greg LaRocque and Jim Mooney. Fingeroth was the editor.

Web of Spider-Man was also home to two more stops on the road to Venom. Issue #18, written by Michelinie with art by Marc Silvestri and Kyle Baker and edited by Jim Owsley, featured a shadowy figure that Spidey’s spider-sense didn’t pick up shoved him onto some subway tracks. The shadowy figured returned in issue #24, written by Michelinie and Len Kaminski with art by Dell Barras and Vince Colletta with editing by Jim Salicrup. This time the figure grabbed Spidey through an open window as he was crawling up the side of a building an threw him off it.

The next year, Salicrup challenges Michelinie, then writer on Amazing Spider-Man, to create a special villain for the 300th issue of that title. Michelinie decided to combine all these elements that came before to create Venom, a woman who blames Spider-Man for the death or her husband and unborn child – both who were lost as collateral damage in a Spider-Man fight. Salicrup thought having the villain be female might be too controversial, so Michelinie decided to make Venom Eddie Brock.

Brock was a reporter who was humiliated when the man he revealed as the serial killer “Sin-Eater” was not actually the killer. He blames Spider-Man, because he brought the real killer to justice. This humiliation caused Brock to get fired and his reputation to get destroyed. This ties into the “Death of Jean DeWolff” storyline from Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man #107-110, written by Peter David and with art by Rich Buckler and Brett Breeding and edited by Jim Owsley.

Brock was retroactively placed in the church in Web of Spider-Man #1 where the symbiote was not destroyed but instead bonded with Eddie Brock.

Adding in Bob McLeod, who was the inker on Amazing Spider-Man #298 & 299 where Venom was first teased, you have at least 27 people who could stake some sort of claim in the creation of Venom. Wait, make that 28. It was latter revealed that the idea of a black, power-enhancing suit for Spider-Man came from a fan, Randy Schuller, who brought it up in a fan letter and for which Jim Shooter paid him $220 so Marvel can use the idea.

So, who should get the credit for creating Venom? Better yet, who should get a cut of the movie cash for doing so? Unlike what Couch says, determining credit is not all that simple.

The collaborative nature of the comic book medium leads to a lot of these “Success has many fathers…” scenarios. Every comic book builds on the stories before it. And every partnership is not the same. The mainstream media seems to look at comic character creation in the simplest of terms. Writers are the fertile grown where all the creation happens so they get the most credit for creating characters. Artists are seen as simply the interpreters of the writer’s concept. It doesn’t always work that way. Alan Moore is known for his complex and detailed scripts. Stan Lee would only give Jack Kirby a sentence or two and let him work his magic. And the “Death of Superman” event sprung out from an editorial retreat with all the Superman writers, with all of them adding elements to the story.

But the fact that it is hard to determine proper creator credit isn’t the reason why creators have such a hard time getting money when their characters hit the big screen. The main reason is that the comic book companies, and their parent corporations, are cheap. Comics sprang out from the world or pulps and were run mostly by shady individuals who wanted to put out as cheap as possible to make as much money as possible.

Let’s take look at the case of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. I wrote about it extensively here and Couch also mentions it. Couch, like just about any one who writes about Siegel and Shuster is practically legally obligated to mention, brings up the fact that the pair signed away the rights to Superman for $130. I believed that to be the case as well, but I realized that was misleading. It make you think DC Comics paid them $130 just for the Superman rights. Not exactly. Their page rate back in 1938 was $10 page for both of them, to be split amongst them however they chose. That $130 was just payment for the 13-page story Siegel wrote and Shuster drew that introduced Superman in Action Comics #1. DC gave them nothing other than that for the rights to the greatest comic book character of all time.

Let’s take look at the case of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. I wrote about it extensively here and Couch also mentions it. Couch, like just about any one who writes about Siegel and Shuster is practically legally obligated to mention, brings up the fact that the pair signed away the rights to Superman for $130. I believed that to be the case as well, but I realized that was misleading. It make you think DC Comics paid them $130 just for the Superman rights. Not exactly. Their page rate back in 1938 was $10 page for both of them, to be split amongst them however they chose. That $130 was just payment for the 13-page story Siegel wrote and Shuster drew that introduced Superman in Action Comics #1. DC gave them nothing other than that for the rights to the greatest comic book character of all time.

And the thing is, they didn’t have to, thanks to the glory of work-for-hire. By signing the check paying them for the work they did, they signed away the rights. The comic book companies owned the characters. The creators became employees. And if you were like Siegel and Shuster, and you fought for money you thought you were owed like they did in 1947, you’d be fired.

Siegel and Shuster only got remuneration in the 1970s when, just before the Superman film went into production, sent open letters to many media outlet describing how he and Shuster were in poverty while DC Comics gets richer and richer. Wary of a public black eye before the release of their major motion picture, DC gave Siegel and Shuster a lifetime stipend, health benefits, and returned “Created by” credits in every Superman book. You can Siegel and Shuster were the original squeaky wheel that got greased.

Not long after DC started giving equity payments to any creator who had a character they created adapted into film. Even though Couch lumps DC in with Marvel in the title a saying they were paying “Shut-up Money” to creators, in the body of the article he writes positively about the company, quoting a number of creators who said that they received far more money from a minor DC character being adapted to the screen than multiple major Marvel characters in their films.

That might have been true at one time, but if Couch dug a little deeper, he would have seen DC might not been all that better than Marvel in this area.

Things started going sour around 2009 when DC Comics became a larger cog of the Warner Brother machine and long-time DC president Paul Levitz stepped down from that position. Levitz, who came up from the ranks of fandom and was a writer himself was generous and liberal in distributing equity payments. When he left, DC changed the rule for getting these kind of rewards. From that point on, the creator would have to write and request equity payments, and if DC considered the character derivative of another DC character, the creator would be eligible for nothing.

This brought the ire from comic creators such as Alan Brennert and Gerry Conway after they were informed that their characters would no longer be eligible for equity payments. Conway even detailed the convoluted way DC decided which character was derivative using Caitlin Snow, who was adapted to the small screen in the CW’s The Flash, which seem more like a way to not make an equity payment at all than than paying one fairly:

Let’s say DC agrees you created a character, like, for example, Killer Frost. In your original creation, Killer Frost had a secret identity named Crystal Frost. Later, a “new” Killer Frost is created for the New 52, and this new Killer Frost has a secret identity named Caitlin Snow.

You’ll be pleased to hear (I hope) that DC agrees I and Al Milgrom are the co-creators of all manifestations of “Killer Frost.” We are also considered the co-creators of Crystal Frost. And, of course, by the twisted logic that credits Power Girl as a derivation of Superman, Al and I must also be the creators of Killer Frost’s New 52 secret identity, Caitlin Snow.

Right?

No. We’re not. And DC insists we are not. And I agree with DC.

Caitlin Snow was created by Sterling Gates and Derlis Santacruz.

Except, according to DC Entertainment, she wasn’t. Because she was “derived” from the original creation of Killer Frost.

Which means Al Milgrom and I created her.

Except, according to DC Entertainment, we didn’t.

Nobody created her.

Or, rather, nobody gets credit and creator equity participation for creating her.

And that, my friends, is truly obnoxious and despicable.

Now, representatives from DC apparently reached out to Conway, and he later issued an apology for his remarks in this blog post. But I can’t find anything online that says that system has changed. But maybe DC made good with Conway because he was the squeaky wheel.

You might ask, when will the system change? When will DC and Marvel do right by their creators? The answer is never. Under the work for hire agreements that comic creators labor under, they have no right to film royalties of equity payments. Any payment is often called a “thank you” payment and is designed to keep them quite more than anything else. I’m sure Aaron Couch thinks his article will be a rallying cry for actual change. But his article was just a regurgitation of all the things we have heard before. He offers no suggestions for calls to action or any possible solutions.

That’s because the possible solution are slim. Should creators unionize? Well, the line to work in comics is a mile long. If people currently working in comics want to unionize, they’ll be fired and replaced by a new body. Should fans stop buying comics in protest? Getting a comic book collector to stop collecting is like asking him to stop breathing.

But if you do want to do something, write a letter or two or twenty to the people running DC and Marvel. Send one to everyone above and editor on the corporate ladder asking creators to be compensated when their characters are adapted to film. And if you have a few spare bucks, give to the Hero Initiative. They are a company designed to help comic creators in need. It might not amount to much, but it will go farther than Aaron Couch and his poorly written article.