Audiences love a good villain. The Academy, maybe not so much.

Take for instance Alan Arkin’s role as the menacing Roat in director Terence Young’s Wait Until Dark. As the man stalking the blind Audrey Hepburn, Arkin turns in a cold and riveting performance, one which has only grown in the estimation of critics and audiences as the years have gone by. Stephen King, writing in his survey of the horror genre Danse Macabre declared the film the scariest movie ever made and praised Arkin’s work in it as perhaps “the greatest evocation of screen villainy ever.” So while it seems somewhat inconceivable now, it seems astonishing that Arkin was overlooked that year when it came time to nominate performances for the Academy Awards.

So what happened? Let’s take a look.

Wait until Dark first started life as a Broadway play by playwright Fredrick Knott. Interestingly, Nought’s two biggest plays both centered on isolated women who are being tormented by strangers in their own homes – Wait Until Dark and Dial M For Murder, which Alfred Hitchcock turned into his only 3D film. We will leave it to Knott’s biographers to explore what this could mean about the playwright.

The story centers on a young woman named Susy Hendrix who has been recently blinded in an accident. Returning home from a business trip, her husband Steve brings her a doll which unbeknownst to both of them is actually stuffed with heroin. Criminals, led by the menacing Roat, had been using the doll to smuggle the drugs into the country but inadvertently let it fall into Steve’s possession. Luring Steve away on the pretense of an out-of-town business emergency, Roat first send in his two henchmen – played by Richard Crenna and Jack Weston – to retrieve the doll, before he has to force his way into the couple’s brownstone to confront a helpless Suzy himself.

Actor/producer Mel Ferrer bought the rights to Wait Until Dark from Knott with the intention of using it as a vehicle for his wife Audrey Hepburn to return to the stage. Hepburn was none too keen on the project though and passed. The role eventually went to Lee Remick, who would star opposite a then-relatively unknown Robert Duvall as Roat.

Premiering at the Ethel Barrymore Theater on Broadway in February 1966, the final act of Wait Until Dark was performed in almost complete darkness, with the theater house lights and exit signs being turned down to help accentuate the darkness on stage. (Good luck getting a fire marshal to sign off on that today.) Despite rave reviews and a Best Actress Tony nomination for Remick, when it came time to adapt the play for the big screen, Ferrer bypassed Remick and again asked Hepburn to take the role of Susy. This time she reluctantly agreed. Ferrer suggested that Hepburn’s assent this time came as the actress was realizing that perhaps she was getting too old to continue playing demure ingenues.

Finding someone to star opposite Hepburn was more of a task. Duvall was an unknown in Hollywood and was never really considered to reprise his role for the film. First George C. Scott and then Rod Steiger were approached to play Roat, but both declined. Finally, someone hit upon the notion of up-and-comer Alan Arkin. The actor had had just scored an unexpected Best Actor Oscar nomination for his big screen debut in the comedy The Russians Are Coming! The Russians Are Coming! and was Hollywood’s hot commodity du jour.

But even that Academy Award nomination under his belt and a good deal of stage experience, he was still relatively new to film. Wait Until Dark was still only his second time in front of the cameras. Hepburn, on the other hand, already had an Oscar win and three additional nominations to her credit. (Her work in this film would earn her her fifth Oscar nomination.) Compounded with the fact that Hepburn’s onscreen and offscreen persona pretty much made her a sweetheart in the eyes of the public and Arkin found himself a bit intimidated on set. As he reminisced during an on-stage appearance at the 2014 TCM Classic Film Festival, “I had a terrible time. I was crazy about her, so I had a miserable three months being mean to her.”

But even that Academy Award nomination under his belt and a good deal of stage experience, he was still relatively new to film. Wait Until Dark was still only his second time in front of the cameras. Hepburn, on the other hand, already had an Oscar win and three additional nominations to her credit. (Her work in this film would earn her her fifth Oscar nomination.) Compounded with the fact that Hepburn’s onscreen and offscreen persona pretty much made her a sweetheart in the eyes of the public and Arkin found himself a bit intimidated on set. As he reminisced during an on-stage appearance at the 2014 TCM Classic Film Festival, “I had a terrible time. I was crazy about her, so I had a miserable three months being mean to her.”

As part of the film’s promotion, a trailer warned potential ticket buyers that the film would replicate the stage play’s second act gimmick of plunging the audience into the darkness of Suzy’s world. “During the last eight minutes of this picture the theater will be darkened to the legal limit to heighten the terror of the breathtaking climax,” a stern voice intoned. “No one will be seated at this time.”

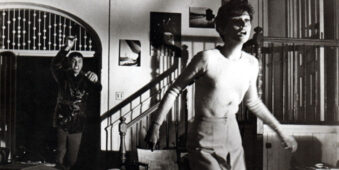

The real draw of the film is not its lights-out gimmick, however, but Arkin’s performance. As Roat, Arkin is cold, calculating and reserved. Maybe not much for the audience to latch onto into terms of relating to the character, but he exudes an aura of menace that palpably infuses every scene he is in. Roat is not a sadist or takes any sort of enjoyment of his tormenting of Suzy. He is more emotionless and driven, a combination that marks him as a ruthless and dangerous man. The film establishes early on that he has killed before and has no compunctions about doing so again. Arkin’s work here is not entirely one note. Roat makes two attempts to gain entrance to Suzy’s apartment before he forces his way, both times in disguise. Essentially as Arkin is playing a character playing a character, and you can see the layered characterization. Overall, his performance established a template that a number of other actors would work from and build off of for similar roles for years to come.

While critics at the time were divided about the film itself, they seemed united with their disapproval of Arkin’s performance. Roger Ebert wrote in the Chicago Sun-Times that Arkin was “not particularly convincing in an exaggerated performance,” while the New York Times’ Bosley Crowther found that his glasses and haircut thought that Arkin was “imitating Jerry Lewis imitating a tough-talking thug.”

And, as noted above, the Academy was not particularly enthusiastic about Arkin’s performance, even though it gave Hepburn another Best Actress nomination for her work in the picture. Granted, that year was a particularly strong one for the Best Supporting Actor category with nominations for John Cassavetes (The Dirty Dozen), Gene Hackman (Bonnie And Clyde), Cecil Kellaway (Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner), Michael J. Pollard (Bonnie and Clyde) and a win for George Kennedy (Cool Hand Luke). It is hard to see whom one would cut from this list to make room for Arkin in if the Academy had been so inclined to consider his performance.

Arkin would go on to received three more Academy Award nominations, winning Best Supporting Actor in 2007 for Little Miss Sunshine. And if he were upset at the lack of recognition for his work in Wait Until Dark, he never let on. If anything, he was self-deprecating about the whole thing, noting later in his life “You don’t get nominated for being mean to Audrey Hepburn.”

And if Academy voters shied away from nominating him because they feared for Audrey Hepburn’s safety in the film, what better testament is there that says perhaps they should indeed have nominated him then?

Alan Arkin is perfectly evil in Wait Until Dark. His measured ruthlessness, when pitted against Hepburn’s wholesome independence, makes the film thrilling to watch. Dealing with Arkin’s Rote is like extending one’s hand in front of a deadly serpent.