In the documentary “They’’ll Love Me When I’m Dead!”, director Orson Welles comments that he does not like people analyzing him by means of the films he has directed. But that is hard to do with something like The Other Side Of The Wind, especially as the just recently finished film will likely stand as the final completed work from the iconic director for us to dissect. And what a masterwork it is.

In the documentary “They’’ll Love Me When I’m Dead!”, director Orson Welles comments that he does not like people analyzing him by means of the films he has directed. But that is hard to do with something like The Other Side Of The Wind, especially as the just recently finished film will likely stand as the final completed work from the iconic director for us to dissect. And what a masterwork it is.

Like a number of Welles’ films, The Other Side Of The Wind opens with a death. In this case, a voice over, whom we later learn is Peter Bogdanovich’s character Brooke Otterlake, tells us that famous film director JJ Hanaford died in a one vehicle car accident the morning after his seventieth birthday party. And what we are about to see is a record of that party pieced together from footage shot by news crews and film students whom he invited to bring cameras into his home.

And right away we are confronted with the genius of Welles as we realize that he basically invented the found footage genre several years before the release of what many consider the start of the genre, the Italian horror film Cannibal Holocaust (1980), and some twenty years before The Blair Witch Project popularized it.

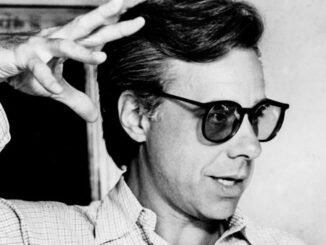

It is tempting, perhaps to draw a parallel between Other Side Of The Wind and Welles’ first film, Citizen Kane. They both are told essentially in flashback after their main character has died. Their central leads are both one-time media titans – Kane as a newspaper man and Hanaford, movies – who have fallen from their lofty positions of power. It is hard not see Welles contemplating his own career trajectory and place in the film history through the lens of Hanaford, played with a Welles-ish irascibility by John Houston. Real life Welles friend and upcoming directorial enfant terrible Peter Bogdanovich playing a similar role to Houston’s Hanaford only solidifies things in the viewer’s mind.

But Citizen Kane is about how power and ambition can warp a man – in this case probably the real life William Randolph Hearst – whereas Wind is a much more personal film. And while Wind is very self-reflective, it also contains Welles’ impish sense of humor, slyly satirizing the emerging first generation of film school educated directors as well as the then-current European art house sensibility. The film’s film-within-a-film, also called The Other Side Of The Wind, is nothing more than actors Bob Random and Welles’ then paramour Oja Kodar wandering around the decaying MGM backlot naked. (Apparently, Welles and his film crew snuck in on weekends without permission.) Susan Strasberg shows up as a very Pauline Kael-like critic. Real life directors Henry Jaglom and Paul Mazursky play themselves as party guests, debating film theory.

And while he is poking fun at these conventions, Welles is also trying them on for size and finding them a remarkably good fit. For the satire to work, the target needs to be both keenly observed and faithfully, to a point, recreated. And Welles’s filmmaking skills are definitely up to the challenge. His work here feels as fresh and energetically inventive as when he made Citizen Kane four decades earlier, as if working in a new form and style has recharged his creative batteries. Nothing he does here visually looks like what he has shot before, but it all still feels very much like an Orson Welles film.

More than just an elongated DVD special feature, the documentary “They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead!” does a great job at contextualizing The Other Side Of The Wind in Welles’ later days career. It cleanly tracks the troubles that Welles had in getting financing for the film, his issues with some actors who needed to be replaced, the fits and starts to which production was confined to and finally to its incomplete status at the time of Welles’ death in 1985.

More than just an elongated DVD special feature, the documentary “They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead!” does a great job at contextualizing The Other Side Of The Wind in Welles’ later days career. It cleanly tracks the troubles that Welles had in getting financing for the film, his issues with some actors who needed to be replaced, the fits and starts to which production was confined to and finally to its incomplete status at the time of Welles’ death in 1985.

But frustratingly, that’s all the story the documentary tells. It leaves out subsequent attempts to get it completed and doesn’t go into all the hurdles that producer Frank Marshall, Welles’ friend Bogdanovich and others needed to go through to realize the’ dream of completing the work on The Other Side Of The Wind. But perhaps that is for another documentary, further down the road. Hopefully we won’t have to wait four decades.