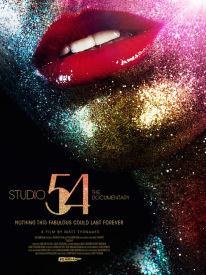

It is hard to extricate the story of famed Manhattan disco Studio 54 from that of its owners and operators Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager. The tale of how the two Brooklynite college buddies segued from owning a string of restaurants to operating the nightclub that was not only seen as the focal point of the disco craze but also the fulcrum for a number of societal changes as well is so tied to the story of the venue itself that when director Matt Tyrnauer’s documentary Studio 54 gets to the point where Rubell and Schrager part ways with the venue and follows the two entrepreneurs, we feel a moment of disconnect from the film itself.

It is hard to extricate the story of famed Manhattan disco Studio 54 from that of its owners and operators Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager. The tale of how the two Brooklynite college buddies segued from owning a string of restaurants to operating the nightclub that was not only seen as the focal point of the disco craze but also the fulcrum for a number of societal changes as well is so tied to the story of the venue itself that when director Matt Tyrnauer’s documentary Studio 54 gets to the point where Rubell and Schrager part ways with the venue and follows the two entrepreneurs, we feel a moment of disconnect from the film itself.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

For the uninitiated, from the moment that it opened its doors on April 26, 1977, Studio 54 was the cultural hot spot in Manhattan and quite possibly the world. It was a place where average folk could share the dancefloor or stand at the bar alongside celebrities like Liza Minelli, Michael Jackson or Andy Warhol. That is, if they could get past Rubell’s mercurial gate-keeping at the entrance. (We are told that Mick Jagger or Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones would be admitted for free but the rest of the band would have to pay a cover charge.) Inside was not just a dance club, but a theatrical experience with loud thumping music, a light show designed by some of Broadway’s finest and constantly changing set pieces.

Much like Studio 54 itself, one needed to get access to truly appreciate what was happening beyond the velvet rope on the sidewalk outside. That access is provided by Schrager himself, who at age 71 appears to be speaking candidly about those days. (Rubell passed away in 1989 of complications from AIDS.) This is the first time that Schrager has really talked in depth about the days of Studio 54 and while his memories are probably somewhat rose-tinted they seem for the most part forthcoming. He does get hesitant at one point towards the end when asked about the accounting irregularities and the skimming of the club’s receipts that ultimately led to him and Rubell doing jail time for tax fraud. (It should be noted that we do see Schrager going over galleys for an upcoming book about the disco, so his reasons for participating with this documentary should be taken with a grain of salt.)

Using copious amounts of footage shot inside the club during its heyday, most of which has never before been released to the public, as well as numerous photos, Tyrnauer and editor Andrea Lewis manage to approximate the nostalgic haze of the interviews of Studio 54 habitués that pepper the film. Frustratingly, though, the photos seem to flash buy almost in time to the 120-beats per minute disco soundtrack. Many are tantalizing images of celebrities or specific themed events and before one can even fully process it or ask themselves “Wow, what’s the story here?” the film has already moved on to the next picture.

Trynauer does a good job at positioning Studio 54 in the late 1970s cultural zeitgeist. Legendary musician Nile Rogers calls Studio 54 “revolutionary,” stating that it was the “first time it felt like people were non-judgmental. Everybody was just fine with everybody’s culture.” At the time, there was new explosion in the fascination with celebrity and the nightclub was as much famous as anyone who walked through its doors. As another interviewee points out, the thirty-three month period that Studio 54 was in operation under Schrager and Rubell fell smack dab between the invention of the Pill and the advent of the AIDS crisis, a time where inhibitions could be shed before the all-too-real consequences began rearing their ugly heads.

But for all that the film does for us to get an idea of what it was like to be invited into the most famous nightclub of the 1970s, it is also very protective of its legacy. It really can’t avoid going into Schrager and Rubell’s problems with the IRS as that is integral to Studio 54’s story. But it is hard to believe that beyond that there wasn’t a dark side to the nearly three-year-long, cocaine-fueled bacchanal. And while Schrager compares his partnership with Rubell as a marriage, the documentary does very little to explore the pair’s friendship and business relationship.