It arrived just over six months after Woodstock and the Tate-LaBianca murders and just over a month and a half after the violent Altamont Free Concert. The U.S. ground involvement in Vietnam was quickly approaching its fifth anniversary, and the violence was about to spread into Cambodia and Laos. Peaceful protests against the war were becoming less and less peaceful, eventually leading to the killing of four Kent State students by Ohio National Guardsmen little over three months after the films release.

It arrived just over six months after Woodstock and the Tate-LaBianca murders and just over a month and a half after the violent Altamont Free Concert. The U.S. ground involvement in Vietnam was quickly approaching its fifth anniversary, and the violence was about to spread into Cambodia and Laos. Peaceful protests against the war were becoming less and less peaceful, eventually leading to the killing of four Kent State students by Ohio National Guardsmen little over three months after the films release.

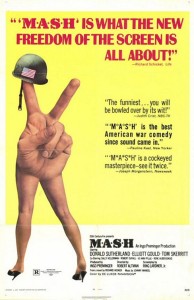

This is the world the film M*A*S*H was released into. The ’60s had become the ’70s, and turmoil was the rule of the day. And the film reflects this tumult in its contradictory nature. It is unabashedly an anti-war film, but one as subtle as it is in your face, as silly as it is smart.

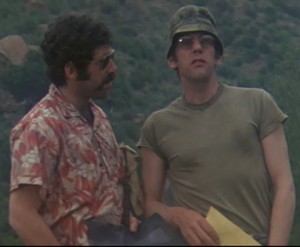

The film opens with new doctors Duke Forrest (Tom Skerritt) and Hawkeye Pierce (Donald Sutherland) arriving at the 4077th, a field hospital three miles from the front lines in South Korea. The pair finds out that the days at the M*A*S*H unit are long periods of absolute boredom interrupted by manic bursts of hyperactivity in the O.R.. In order to stay sane, the doctors resort to sex, booze and wacky pranks to fill up their days. Their comedy schtick doesn’t set well with bible-thumping Frank Burns (Robert Duvall) and straight-laced Margaret O’Houlihan (Sally Kellerman), who wish the boys would shape up or ship out. However, Burns and O’Houlihan are soon outmatched when a new surgeon, Trapper John McIntyre (Elliot Gould), joins Forrest and Pierce to create even more anarchy.

The film opens with new doctors Duke Forrest (Tom Skerritt) and Hawkeye Pierce (Donald Sutherland) arriving at the 4077th, a field hospital three miles from the front lines in South Korea. The pair finds out that the days at the M*A*S*H unit are long periods of absolute boredom interrupted by manic bursts of hyperactivity in the O.R.. In order to stay sane, the doctors resort to sex, booze and wacky pranks to fill up their days. Their comedy schtick doesn’t set well with bible-thumping Frank Burns (Robert Duvall) and straight-laced Margaret O’Houlihan (Sally Kellerman), who wish the boys would shape up or ship out. However, Burns and O’Houlihan are soon outmatched when a new surgeon, Trapper John McIntyre (Elliot Gould), joins Forrest and Pierce to create even more anarchy.

For those of you familiar only with the M*A*S*H television show, you might be wondering who that Duke Forrest is. And, while watching the film for the first time, might get a bit anxious for Max Klinger to show up. The thing is, while the film was adapted from from the same source material, Richard Hooker’s 1968 novel MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors (based loosely on Hooker’s –real name was Dr. H. Richard Hornberger–experiences in Korea), the TV series wasn’t exactly adapted from the feature film. There are similarities, most notably Gary Burgoff’s Radar appearing in both, but each varies from the source material in its own special way.

For those of you familiar only with the M*A*S*H television show, you might be wondering who that Duke Forrest is. And, while watching the film for the first time, might get a bit anxious for Max Klinger to show up. The thing is, while the film was adapted from from the same source material, Richard Hooker’s 1968 novel MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors (based loosely on Hooker’s –real name was Dr. H. Richard Hornberger–experiences in Korea), the TV series wasn’t exactly adapted from the feature film. There are similarities, most notably Gary Burgoff’s Radar appearing in both, but each varies from the source material in its own special way.

This was the third feature film of Robert Altman’s storied career. Altman was at the time known mostly for his television work and had 1967’s Countdown (which also featured Duvall and Michael Murphy, who appears in M*A*S*H as an anesthesiologist friend of Hawkeye’s) and 1969’s That Cold Day in the Park (also featuring Murphy, who would become a frequent collaborator of Altman’s) as the entirety of his film resume to that point. But it was his television background that helped him the most here, because M*A*S*H isn’t really a film. It’s a series of scenes held together by a common theme. There is no real narrative to the film, no rising action/climax/resolution either. Duke and Hawkeye are essentially the same people at the end of the movie as they are at the beginning. It is what the novel was–a series of wartime reminiscences collected all in one place with the thinnest connective tissue holding them together.

This was the third feature film of Robert Altman’s storied career. Altman was at the time known mostly for his television work and had 1967’s Countdown (which also featured Duvall and Michael Murphy, who appears in M*A*S*H as an anesthesiologist friend of Hawkeye’s) and 1969’s That Cold Day in the Park (also featuring Murphy, who would become a frequent collaborator of Altman’s) as the entirety of his film resume to that point. But it was his television background that helped him the most here, because M*A*S*H isn’t really a film. It’s a series of scenes held together by a common theme. There is no real narrative to the film, no rising action/climax/resolution either. Duke and Hawkeye are essentially the same people at the end of the movie as they are at the beginning. It is what the novel was–a series of wartime reminiscences collected all in one place with the thinnest connective tissue holding them together.

As I mentioned above, it was an anti-war movie but a subtle one. No, there would be no character giving an impassioned, garment ripping speech about man’s inhumanity to man, no obvious tales of innocence lost, and no big character arc that show how war changes a man. The one character that goes insane was not from the horrors of war but from the horrors of teasing by Hawkeye, Trapper and Duke. Altman, a World War II veteran himself, shows how war really was for the warrior. It sucked, but you cope the best way you can. For Trapper and Hawkeye, it was acting like the Marx Brothers on acid.

As I mentioned above, it was an anti-war movie but a subtle one. No, there would be no character giving an impassioned, garment ripping speech about man’s inhumanity to man, no obvious tales of innocence lost, and no big character arc that show how war changes a man. The one character that goes insane was not from the horrors of war but from the horrors of teasing by Hawkeye, Trapper and Duke. Altman, a World War II veteran himself, shows how war really was for the warrior. It sucked, but you cope the best way you can. For Trapper and Hawkeye, it was acting like the Marx Brothers on acid.

Where Altman gets the anti-war message across is in the surgery scenes. The director did not hold back in presenting brutal reality of war in these scenes. The operating room was full of so much blood and gore that you’d think you were watching a Herschell Gordon Lewis film. The doctors’ pristine white surgical gowns are constantly dyed red with human blood. There’s a particularly gruesome scene where blood sprays out of a wounded soldier’s neck like a fountain. It’s horrific, and it’s meant to be. And the doctor’s laissez faire, “bring in the next one” attitude towards the victims, a necessity in this case, makes all the more horrifying. It shows what the true cost of war is in dying color.

Where Altman gets the anti-war message across is in the surgery scenes. The director did not hold back in presenting brutal reality of war in these scenes. The operating room was full of so much blood and gore that you’d think you were watching a Herschell Gordon Lewis film. The doctors’ pristine white surgical gowns are constantly dyed red with human blood. There’s a particularly gruesome scene where blood sprays out of a wounded soldier’s neck like a fountain. It’s horrific, and it’s meant to be. And the doctor’s laissez faire, “bring in the next one” attitude towards the victims, a necessity in this case, makes all the more horrifying. It shows what the true cost of war is in dying color.

But more than being anti-war, the film is really anti-establishment. The only authority figure that comes off looking anywhere near good is Colonel Blake (Roger Bowen), and that’s only because he pretty much gets out of the way and lets the boys do their jobs. The rest of the Generals, Colonels and Majors are portrayed as either self-centered boors who treat their underlings as props to make themselves look better, petite tyrants who enjoy the sense of power their ranks give them, or slaves to regulations and procedures above all else–including even common sense.

But more than being anti-war, the film is really anti-establishment. The only authority figure that comes off looking anywhere near good is Colonel Blake (Roger Bowen), and that’s only because he pretty much gets out of the way and lets the boys do their jobs. The rest of the Generals, Colonels and Majors are portrayed as either self-centered boors who treat their underlings as props to make themselves look better, petite tyrants who enjoy the sense of power their ranks give them, or slaves to regulations and procedures above all else–including even common sense.

And Hawkeye, Duke and Trapper rebel against all authority figures, to the point of their abject humiliation–be it in the form of having their lovemaking session broadcast over the camp’s P.A. system or staging photos of them with prostitutes to use as blackmail fodder. The message is that authority only has the power over you that you give to them and if the people in power do not understand that, they should be open to mock and ridicule. That’s a sentiment I imagine a lot people in the counterculture movement of the time could really get behind.

And Hawkeye, Duke and Trapper rebel against all authority figures, to the point of their abject humiliation–be it in the form of having their lovemaking session broadcast over the camp’s P.A. system or staging photos of them with prostitutes to use as blackmail fodder. The message is that authority only has the power over you that you give to them and if the people in power do not understand that, they should be open to mock and ridicule. That’s a sentiment I imagine a lot people in the counterculture movement of the time could really get behind.

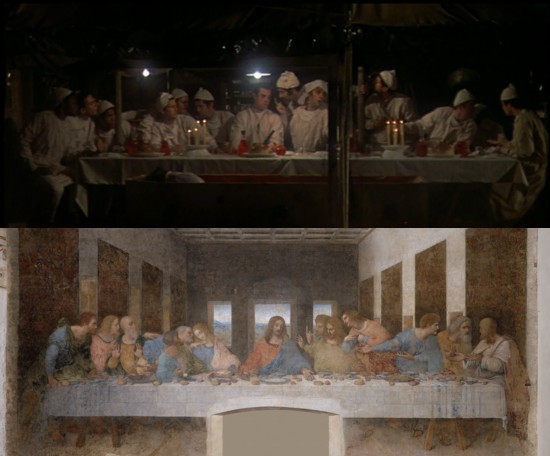

Military authority isn’t the only establishment the film challenges. Organized religion falls into the film’s cross hairs as well. Frank Burns is presented as a devout Christian, who prays so much that Duke and Hawkeye ask to have him removed from their tent. Later, he is revealed as a hypocrite as he zestfully enters into an extra-marital affair with O’Houlihan,even going so far as to say it is God’s will that he break that commandment. Father Mulcahy is interrupted giving Last Rites to dead soldier in the O.R. by Duke, who ask his help to hold a retraction on another patient. ” I’m sorry, but this man is still alive and that other man is dead, and that’s a fact,” Duke says in a short line rife with subtext. And when the doctors gather the night before Walter Waldowski’s “suicide,” Altman has them arranged behind a long dinner table, each man positioned almost exactly as an apostle was in Leonardo DaVinci’s “The Last Supper” was (see below for a comparison).

Military authority isn’t the only establishment the film challenges. Organized religion falls into the film’s cross hairs as well. Frank Burns is presented as a devout Christian, who prays so much that Duke and Hawkeye ask to have him removed from their tent. Later, he is revealed as a hypocrite as he zestfully enters into an extra-marital affair with O’Houlihan,even going so far as to say it is God’s will that he break that commandment. Father Mulcahy is interrupted giving Last Rites to dead soldier in the O.R. by Duke, who ask his help to hold a retraction on another patient. ” I’m sorry, but this man is still alive and that other man is dead, and that’s a fact,” Duke says in a short line rife with subtext. And when the doctors gather the night before Walter Waldowski’s “suicide,” Altman has them arranged behind a long dinner table, each man positioned almost exactly as an apostle was in Leonardo DaVinci’s “The Last Supper” was (see below for a comparison).

As pointed, valid and witty as some of the commentary is, there are elements that seemed dated to put it kindly or downright offensive if we’re not so kind. The nurses’ off hours are provided to them so they can essentially be concubines for the doctors. During their working hours? Their worth is determined by the doctor’s opinion of them. Being gay is viewed in such a negative that suicide would be preferable (that’s why Waldowski wanted to kill himself, he thought he was a “fairy”). And while the southerner Duke’s reticence to have the African-American Oliver Jones be his bunkmate was Altman’s subtle way of addressing the racial politics of the day, there’s no way to avoid Jones’ “Spearchucker” nickname as being anything but offensive, no matter how many javelins he threw in college.

As pointed, valid and witty as some of the commentary is, there are elements that seemed dated to put it kindly or downright offensive if we’re not so kind. The nurses’ off hours are provided to them so they can essentially be concubines for the doctors. During their working hours? Their worth is determined by the doctor’s opinion of them. Being gay is viewed in such a negative that suicide would be preferable (that’s why Waldowski wanted to kill himself, he thought he was a “fairy”). And while the southerner Duke’s reticence to have the African-American Oliver Jones be his bunkmate was Altman’s subtle way of addressing the racial politics of the day, there’s no way to avoid Jones’ “Spearchucker” nickname as being anything but offensive, no matter how many javelins he threw in college.

For many, the film M*A*S*H will be remembered as the movie that spawned the beloved TV series. But it was a film that was both indicative of the times and a harbinger of the future. And it is a film that is just as interesting on its 45th birthday as it was on the day it was released.

Theresa Laity liked this on Facebook.

William Gatevackes liked this on Facebook.