In a multi-part series, Comic Book Film Editor William Gatevackes will be tracing the history of comic book movies from the earliest days of the film serials to today’s big blockbusters and beyond. Along with the history lesson, Bill will be covering some of the most prominent comic book films over the years and why they were so special. This time, we cover the meteoric rise, and the controversial fall of the legendary Frank Miller.

You can engage in a healthy debate as to what was high point of Frank Miller’s career. Some might say it was when he took over the writing chores on Daredevil in 1980, because that set up the legendary run that paved the way for everything else. Others might say that it was 1986, when his masterpiece, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, was released. A few might say it was in 1991 when he created Sin City, the creator-owned property that caught Hollywood’s eye.

You can engage in a healthy debate as to what was high point of Frank Miller’s career. Some might say it was when he took over the writing chores on Daredevil in 1980, because that set up the legendary run that paved the way for everything else. Others might say that it was 1986, when his masterpiece, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, was released. A few might say it was in 1991 when he created Sin City, the creator-owned property that caught Hollywood’s eye.

Personally, I am leaning towards 2007. He was coming off two successful adaptations of his original properties and was tapped to do the unheard of–to write and direct a film adaptation of a comic created by one of his idols. However, this date is problematic because his artistic decline in the world of comics had started years earlier.

You can call Frank Miller’s rise in comic books meteoric. Yes, he got his start as many creator is the late 1970s did–doing art in anthologies and fill-in stories to help regular artists out. But while many creators languished in this freelancer hell for years before getting steady work, Miller was hired as the regular artist on Daredevil with issue #158 in under a year. Granted, when Miller joined the title, it was practically on life support. It was one of Marvel’s lowest selling titles, and was moved to a one every two months shipping schedule.

You can call Frank Miller’s rise in comic books meteoric. Yes, he got his start as many creator is the late 1970s did–doing art in anthologies and fill-in stories to help regular artists out. But while many creators languished in this freelancer hell for years before getting steady work, Miller was hired as the regular artist on Daredevil with issue #158 in under a year. Granted, when Miller joined the title, it was practically on life support. It was one of Marvel’s lowest selling titles, and was moved to a one every two months shipping schedule.

The book was flirting with cancellation when Miller to over the writing duties on the title to go along with his art chores starting with issue #168 under a year later. Odds are that if the book wasn’t in such rough shape, he might not have received this unprecedented chance. But he did, and he became a superstar over it.

Miller turned a character that was essentially a poor-man’s Spider-Man, only with a negligible handicap (blindness, more than over compensated by a radar sense) and a less impressive rogue’s gallery, into something special. Miller turned the book in to a crime noir fable with Asian overtones. The character spent as much time fighting ninjas as he did crime bosses. But the stories Miller created fit his cinematic art style and lifted the character to a place in prominence. Without Miller, Daredevil would never have been made into a film, and most likely be a curiosity lining the dustbin of Marvel’s once popular characters.

Miller turned a character that was essentially a poor-man’s Spider-Man, only with a negligible handicap (blindness, more than over compensated by a radar sense) and a less impressive rogue’s gallery, into something special. Miller turned the book in to a crime noir fable with Asian overtones. The character spent as much time fighting ninjas as he did crime bosses. But the stories Miller created fit his cinematic art style and lifted the character to a place in prominence. Without Miller, Daredevil would never have been made into a film, and most likely be a curiosity lining the dustbin of Marvel’s once popular characters.

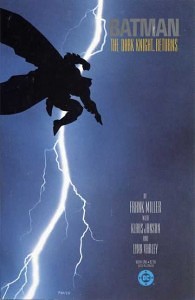

After completing his run on Daredevil, Miller moved on to DC Comics and one of their most famous characters, Batman. His Batman: The Dark Night Returns featured an older, retired crime fighter who feels compelled to put the cape and cowl back on as the world slips into lawless anarchy.

If Miller’s take on Daredevil was comic book film noir, then his take on Batman was comic book film noir on steroids. And acid. With a little crystal meth thrown in for good measure. It was a shockingly daring deconstruction of the sacred DC institution, one that could not happen in the Intellectual Property focused world of today.

The series was incredible influential. Along with Watchmen, it inspired a “grim and gritty” trend in comics, got a lot of attention in the mainstream press and inspired the cinematic versions of Batman that followed in its wake. If Daredevil made Frank Miller a superstar, Dark Knight Returns made him a legend–both in and out of comic books.

The series was incredible influential. Along with Watchmen, it inspired a “grim and gritty” trend in comics, got a lot of attention in the mainstream press and inspired the cinematic versions of Batman that followed in its wake. If Daredevil made Frank Miller a superstar, Dark Knight Returns made him a legend–both in and out of comic books.

Miller used his newfound status and power to the fullest advantage. He first stepped his toes in the Hollywood pond by doing the screenplays to RoboCop 2 and RoboCop 3 in the 1990s, although that experience left a bad taste in Miller’s mouth. That decade was also when Miller moved on to creator-owned fare.

Miller used Dark Horse Comics as the publisher of his original creations, and his first offerings were the thoughtful, if uber-violent Hard Boiled (which he did with Geoff Darrow art) and Give Me Liberty (which he did with Dave Gibbons on art). His third effort, which he did art as well writing on, was the one we’re talking about today.

Sin City first appeared in serialized form in Dark Horse Presents #51, and showed what Miller could do with his noir stylings when not hampered by working on another company’s characters. Printed in black and white, which help accentuate Miller’s art work and his use of shadow and shading. Sin City told the story of Basin City, a corrupt and morally bankrupt town where even the good guys have a little bit of dirt on them and the women are as tough as they are beautiful. It’s a town where cops are easily bought, the prostitutes take care of themselves, and crossing the wrong people will inevitably lead to your death.

Sin City first appeared in serialized form in Dark Horse Presents #51, and showed what Miller could do with his noir stylings when not hampered by working on another company’s characters. Printed in black and white, which help accentuate Miller’s art work and his use of shadow and shading. Sin City told the story of Basin City, a corrupt and morally bankrupt town where even the good guys have a little bit of dirt on them and the women are as tough as they are beautiful. It’s a town where cops are easily bought, the prostitutes take care of themselves, and crossing the wrong people will inevitably lead to your death.

This was an example of world-building at its finest. It was a fun house mirror reflection of the graft and crime that plague American cities, with an element of the fantastic to it as well. Sin City eventually became a blanket heading for all the crime noir Frank Miller wanted to write. It was home to a number of different stories, and often times a supporting character in one story arc would become the lead in the next, and someone who appears in the background would prove to be very important later on down the line.

The series caught the attention of director Robert Rodriguez, who desperately wanted to make a film of the graphic novel. However, Miller, who was burned by Hollywood before, was reluctant to let his baby be fed to the Tinseltown Wolves. Rodriguez was insistent, and created a short film with his own money from one of Miller’s Sin City tales to show that he was going to be respectful to the original text. The short film became “The Customer Is Always Right,” which became the opening segment of 2005’s Sin City. Yes, Rodriguez’s passion and dedication one Miller over, but I’m sure the offer of co-directorship helped too.

The test footage also got Rodriguez an awesome, all-star cast, including Mickey Rourke, Bruce Willis, Jessica Alba, Clive Owen, Rosario Dawson, Benicio Del Toro, Michael Clarke Duncan, and many, many more. It would be hard not to make a great film with the cast that Rodriguez had, and a great film he did make.

The test footage also got Rodriguez an awesome, all-star cast, including Mickey Rourke, Bruce Willis, Jessica Alba, Clive Owen, Rosario Dawson, Benicio Del Toro, Michael Clarke Duncan, and many, many more. It would be hard not to make a great film with the cast that Rodriguez had, and a great film he did make.

The film looked like Basin City was magically transported from the page and pasted to the screen. It was one of the first use of extensive green screen technology, and this helped Rodriguez create a visually stunning, realistic yet ethereal world for the movie to take place in. The film was co-directed by Miller and Rodriguez, with Quentin Tarantino on board directing one scene. The result was a film that looked quite unlike any other film ever made, and one of the most faithful comic book adaptations of all time.

The film made over $158 million worldwide at the box office against a $45 million budget. It seemed audiences were responsive to films that did a shot-by-shot, green screen backlot adaptation of Frank Miller’s graphic novels. This was good news the the producers of 300.

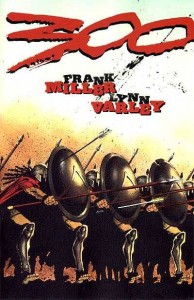

The film was based on Frank Miller’s 1998 miniseries retelling the historic Battle of Thermopylae from 480 B.C., where a small group of Greek soldiers were able to hold off the vastly superior forces of the invading Persian army for three days during the second Persian invasion of Greece. The battle has been inspiration for or referenced in numerous poems, novels and movies over the centuries. Miller himself has often referenced the battle in Sin City so his choosing to build a whole graphic novel around it is not surprising.

The film was based on Frank Miller’s 1998 miniseries retelling the historic Battle of Thermopylae from 480 B.C., where a small group of Greek soldiers were able to hold off the vastly superior forces of the invading Persian army for three days during the second Persian invasion of Greece. The battle has been inspiration for or referenced in numerous poems, novels and movies over the centuries. Miller himself has often referenced the battle in Sin City so his choosing to build a whole graphic novel around it is not surprising.

From an artistic standpoint, it was one of Miller’s best works. The story was presented in nothing but double-paged spreads–where the graphics are designed to spill out over two comic book pages and, unlike Sin City this one was masterly colored by Miller’s then paramour and go-to colorist, Lynn Varley.

However, critics were quick to point out the historical inaccuracies in the work (Alan Moore even famously quipped “You know, I mean, read a book, Frank.”) and made issue with certain homophobic statements by the characters.

These criticisms did not stop filmmakers from wanting to adapt Miller’s version of the battle, especially Zack Snyder, who long wanted to helm the adaptation of the graphic novel. He would eventually get his chance when he was hired in 2004 to bring the comic to the screen. Snyder and Miller’s version beat another movie about the battle that was spearheaded by director Michael Mann into theaters. Mann’s version has yet to come to fruition.

These criticisms did not stop filmmakers from wanting to adapt Miller’s version of the battle, especially Zack Snyder, who long wanted to helm the adaptation of the graphic novel. He would eventually get his chance when he was hired in 2004 to bring the comic to the screen. Snyder and Miller’s version beat another movie about the battle that was spearheaded by director Michael Mann into theaters. Mann’s version has yet to come to fruition.

The film was shot almost completely on a sound stage in front of blue screens. Snyder used the comic as a story board, with numerous scenes captured on screen almost exactly as they appeared in the comic book. It wasn’t an exact translation, however. Snyder did add scenes back in Sparta to flesh out the story more.

Snyder capture the grandeur and grittiness of the comic book. His film is incredibly stylized, and his “stop/go” slow motion technique employed here briefly became his trademark. Snyder definitely grabs your attention.

The film, like the comic before it, also spawned controversy. In addition to the questions of historical accuracy and homophobia, critics singled out what they thought was a fascist agenda, a negative portrayal of people disabilities and Iran was none too pleased with how the Persians were seen in the movie. However, none of this stopped the film from becoming a hit. The film made more than it’s $65 million budget in its opening weekend in America alone, going on to a worldwide gross of over $456 million. It jump started the careers of Gerard Butler and Michael Fassbender and made Snyder a go-to director for comic book epics. It also spawned a sequel.

300: Rise of An Empire was supposed to be based on a graphic novel by Frank Miller called Xerxes, named for the Persian leader. Only one problem, Frank Miller never got around to writing that sequel to 300, so producers had to come up with a sequel on their own.

300: Rise of An Empire was supposed to be based on a graphic novel by Frank Miller called Xerxes, named for the Persian leader. Only one problem, Frank Miller never got around to writing that sequel to 300, so producers had to come up with a sequel on their own.

Also missing were Butler and Fassbender (except in a flashback to the first film) and Zack Snyder handed the directorial reins over to Noam Murro, but still keeping a hand in writing and producing the film. The sequel acts as a counterpoint to 300, focusing on events that happened before and during that film as well as after. The main crux of the story is the battle of Salamis, a naval battle that set the stage for the Greeks finally repelling the Persian invasion. Sullivan Stapleton take over the lead as Themistocles of Athens.

You couldn’t help but feel that something was missing because, well, a lot WAS missing. But, nonetheless, even though it failed to earn back its $110 million budget in its US release earlier this year (earning just over $106 million), it tripled its budget worldwide with over $331 million in grosses. No word if another sequel will be wrung from the Second Invasion of Greece.

After the one-two punch of Sin City and 300, Frank Miller was Hollywood’s darling. They weren’t sure what it was about him that resonated with audiences, but they knew it was something. So even though he had only a handful of screenwriting credits to his name and only one co-directorship under his belt, producers hired Miller in 2006 after the success of Sin City to write and direct the long-in-development The Spirit. The success of 300 made them feel much better about their decision

They really should have done their due diligence, because Miller’s comic book work at the time would have told them exactly what they were getting into.

From 2000 on, Miller’s comic book work has been a case of diminishing returns. It all started with the ill-advised The Dark Knight Strikes Again, a sequel to The Dark Knight Returns. Instead of a tersely plotted examination of the mythos behind the heroes of the DC Universe that marked the original, one that balanced grim and gritty realism with a finely tuned sense of the outrageous, what the sequel delivered was Miller’s tone deaf characterization and a book where the outrageous and cartoon-like chased and sense of realism out the window. It was a sloppy presentation, and one that tarnished the original masterpiece it followed.

From 2000 on, Miller’s comic book work has been a case of diminishing returns. It all started with the ill-advised The Dark Knight Strikes Again, a sequel to The Dark Knight Returns. Instead of a tersely plotted examination of the mythos behind the heroes of the DC Universe that marked the original, one that balanced grim and gritty realism with a finely tuned sense of the outrageous, what the sequel delivered was Miller’s tone deaf characterization and a book where the outrageous and cartoon-like chased and sense of realism out the window. It was a sloppy presentation, and one that tarnished the original masterpiece it followed.

Miller wasn’t done with Batman yet. In 2005, he paired with superstar artist Jim Lee on All-Star Batman and Robin. I reviewed the first three issues here, and my opinion of how awful it was has not improved since that review was published. Once again, Miller loses the hold he had on Batman’s characterization, only this time he makes him a petulant and whiny child abuser who might just be clinically insane. The story went absolutely nowhere over the ten issues that were published, a fact not helped by the title’s chronic lateness (three years to publish ten issues). The series has been on “hiatus” since 2008, and it’s telling that no one has been clamoring for it to be completed.

Miller’s third attempt at doing a Batman story for DC is the one that sounded bad from the get go. Holy Terror, Batman! was Miller’s commentary on the War on Terror, using Batman as a surrogate, sending him after Osama Bin Laden and Al-Qaeda. Eventually, according to Miller, he removed the project from DC Comics because he decided it went too far for Batman. I’m sure DC didn’t mind it leaving. So Miller took the cape off of Batman, gave him some guns and took the novel to Legendary Comics. The result, renamed Holy Terror, is a jingoistic screed filtered through Miller’s extreme right-wing views (he made the papers for his condemnation of the Occupy movement in 2011) that was as inflammatory as it was poorly written.

Miller’s third attempt at doing a Batman story for DC is the one that sounded bad from the get go. Holy Terror, Batman! was Miller’s commentary on the War on Terror, using Batman as a surrogate, sending him after Osama Bin Laden and Al-Qaeda. Eventually, according to Miller, he removed the project from DC Comics because he decided it went too far for Batman. I’m sure DC didn’t mind it leaving. So Miller took the cape off of Batman, gave him some guns and took the novel to Legendary Comics. The result, renamed Holy Terror, is a jingoistic screed filtered through Miller’s extreme right-wing views (he made the papers for his condemnation of the Occupy movement in 2011) that was as inflammatory as it was poorly written.

Miller, in interviews at the time, came off as a man who believed his own hype a little bit too much. Everyone called him a genius, so he was one. And everything he touches is automatically perfect because of this, no matter how poorly written it is. Unfortunately, this attitude was encouraged. His Martha Washington Dies, the coda to his Give me Liberty series, featured 17 pages of an elderly woman talking to a group of undefined soldiers on a battlefield, about to fight in an undefined war. After she is done talking, she dies. If a novice writer submitted this to a comic book company, the editor would put his name on a dry erase board marked ” Never Hire This Person.” Since it’s Frank Miller, they slap a glossy cover on it, charge $3.50 for it, as shill it to the fans.

But this was in the field of comics, where he paid his dues and made his legend. Certainly his attention to quality would be sharper in his feature film debut? Unfortunately not.

The Spirit was a tough character to bring to the screen. Will Eisner created a character that could move freely from crime noir to whimsy to adventure. It was a tone that filmmakers from William Freidkin to Brad Bird couldn’t bring it to the big screen in a way that would please the studios. It seemed like that they would never find a creator who got the character and could capture its essence.

The Spirit was a tough character to bring to the screen. Will Eisner created a character that could move freely from crime noir to whimsy to adventure. It was a tone that filmmakers from William Freidkin to Brad Bird couldn’t bring it to the big screen in a way that would please the studios. It seemed like that they would never find a creator who got the character and could capture its essence.

However, they thought they found one in Frank Miller. Miller was a friend and follower of Eisner (he was actually offered the job directing The Spirit at Eisner’s funeral). If he couldn’t bring the character to the big screen and do it justice, no one could.

Well, apparently, no one could.

Frank Miller’s The Spirit was relentlessly awful. It was aggressively awful. And not in a “so-bad-it’s-good” way either. It was bad in a “so-bad-why-am-I-watching-this” way.

For a man who was so protective of his own comic work, Miller certainly didn’t have any qualms about messing with Eisner’s most famous characters. Eisner’s Spirit was a charming man with a winning personality. Miller’s Spirit was was a bland cypher whose only flash of personality came when he spewed Sin City-esque doggerel. Eisner kept the Spirit’s nemesis, The Octopus, hidden to increase his mystery and allure. Miller put the Octopus front and center on screen, cast Samuel L. Jackson in the role and apparently only gave him one direction-chew as much scenery as possible. Jackson is probably still picking splinters from his teeth today.

Eisner’s women were legendary. They were sultry and seductive and you totally believe that the Spirit was tempted to join them on the dark side. Miller’s decided to put most of Eisner’s femme fatales in the movie, cast some of the most beautiful in the world, and makes each of them as exciting as expired toothpaste. Eisner’s stories were filled with gentle wit and humor. Miller’s humor was crass, crude and campy. While Rodriguez and Snyder used the green screen to create a rich and fully realized world, Miller used the same technology to create a murky and muddled mess that looked like some one spilled a big pot of India ink over it.

In other words, The Spirit was a failure on every single level. Miller’s inexperience showed through, yet so did his arrogance. He thought he was creating art. What puzzles me is how it went through without anyone saying how horrible it was.

Miller has not made a comic book since Holy Terror, but he will have a chance to redeem himself cinematically as he reteams with Robert Rodriguez next month as the Sin City: A Dame to Kill For hits theaters.

The film adapts two of Miller’s stories from the comics in addition to, and this is the worrisome part by Miller, two original stories written directly for the screen. A lot of the original cast returns, including Rosario Dawson, Bruce Willis, Jessica Alba, and Mickey Rourke, joined by newcomers such as Josh Brolin, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Eva Green and Lady Gaga.

The film adapts two of Miller’s stories from the comics in addition to, and this is the worrisome part by Miller, two original stories written directly for the screen. A lot of the original cast returns, including Rosario Dawson, Bruce Willis, Jessica Alba, and Mickey Rourke, joined by newcomers such as Josh Brolin, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Eva Green and Lady Gaga.

Perhaps going back to Basin City will be the best thing for Miller. Perhaps it will mean a return to quality for the legend. However, it will take a lot to over come the damage Miller has done to his legacy. This might not be enough.

Next time: Ghost Rider.

HISTORY OF COMIC BOOK FILMS: The Rise And Fall Of Frank Miller http://t.co/alof6HbJJu

William Gatevackes liked this on Facebook.

An thoughtful, engaging and well-researched piece on Frank Miller. Sadly we now know the reception to the follow up film to Sin City was tepid. In an odd way I see a similarity in Miller to how Steve Ditko squandered his imagination and talent in servitude to a narrow ideological concerns. Of course Miller had a different kind of success and impact than Ditko, but they compare in that they are two talented visual story-tellers who in the latter part of their careers seemed more intent on lecturing their audiences than in telling gripping stories or creating fully fleshed-out characters.

A mostly fair – if just a tad shrill at times – take on his recent creative output, with (IMHO) one exception: “Martha Washington Dies” was written merely to be the epilogue to a giant collection of the entire Martha Washington series, to tie a bow around the whole thing that had started with her birth and therefore felt natural to bookend with her death. It was never intended as a standalone work, and its a bit unfair to judge it as one. The only reason it was published individually was a nice gesture to not screw over longtime fans,… Read more »

[…] reading: History of Comic Book Films: The Rise and Fall of Frank Miller // The 300 Contoversy: A Case Study in the Politics of […]