In a multi-part series, Comic Book Film Editor William Gatevackes will be tracing the history of comic book movies from the earliest days of the film serials to today’s big blockbusters and beyond. Along with the history lesson, Bill will be covering some of the most prominent comic book films over the years and why they were so special. Today, we continue our profile of Alan Moore and take a look at the film adaptation of one of his most political works.

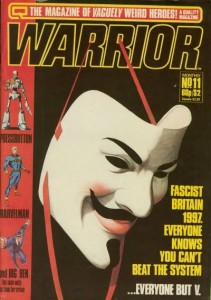

V for Vendetta started out in 1982 as a black and white serial in Warrior magazine for Britain’s Quality Comics. Created by Alan Moore and David Lloyd, it was not able to finish its run in that magazine due to Warrior being cancelled with the serial only 60% completed.

V for Vendetta started out in 1982 as a black and white serial in Warrior magazine for Britain’s Quality Comics. Created by Alan Moore and David Lloyd, it was not able to finish its run in that magazine due to Warrior being cancelled with the serial only 60% completed.

It’s interesting to think about what might have happened if the story was allowed to complete its natural run in that British publication. If it did, DC Comics would have probably been less likely to purchase the rights to the story so it could be completed. The story might not have gotten as much exposure but it might not have been another straw that broke the camel’s back that was Alan Moore’s relationship with DC. It might not have ever been made into a film, and it might not have had the cultural impact that it currently enjoys.

On the surface, V seems very much like many of the other characters that appeared in British comic books at the time. He was a violent adventurer living in a dystopian future—like Judge Dredd, Strontium Dog and Rogue Trooper. But Moore took a turn away from the more fantastic science fiction elements of those characters and set V in a world that was chillingly real—a fascistic Britain set in a near-future that seems all too plausible in the ultraconservative Thatcher-era England Moore wrote the story in.

The series is set in 1997, most of the world is a nuclear wasteland and while Britain was left unscathed by the war, its struggling with the upheaval of the world economy allows a fascistic government to come to power. The British government has eyes and ears in every household, and the news is dictated to the masses through the government’s propaganda arm. Undesirables are rounded up and sent to concentration camps where they are either killed or experimented on.

Into this world comes V, an anarchist whose primary goal appears to be the overthrow of the fascists in charge. However, his crusade has a much more personal motive, one that changes his fight for freedom into a vendetta.

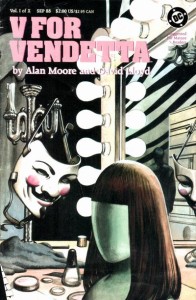

Warrior was cancelled in 1985 and the feature went on hiatus for three years when in 1988 DC Comics, who at the time Moore still had a good working relationship with, agreed to buy the rights to the story, color the original black and white installments, and allow Moore and Lloyd to finish the story as a 10 issue miniseries. DC even wrote up a contract similar to the one Moore had for Watchmen that when V for Vendetta went out of print, the rights would have reverted Moore and Lloyd.

Warrior was cancelled in 1985 and the feature went on hiatus for three years when in 1988 DC Comics, who at the time Moore still had a good working relationship with, agreed to buy the rights to the story, color the original black and white installments, and allow Moore and Lloyd to finish the story as a 10 issue miniseries. DC even wrote up a contract similar to the one Moore had for Watchmen that when V for Vendetta went out of print, the rights would have reverted Moore and Lloyd.

That was also the year when producer Joel Silver bought the rights to both Watchmen and V for Vendetta from DC Comics (with Moore and his respective co-creators getting a cut of the grosses). Silver claims that Moore was positive and enthusiastic about the properties being made into films. But since that time, Moore had a contentious break-up with DC tied to both Watchmen and V for Vendetta, the rights to which never reverted to Moore because they never went out of print—a fact that Moore considers as DC swindling him, and had a horrible experience with Hollywood over The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen which caused him to remove all involvement with film adaptations of his work. Either Silver was ignorant about these attitude changes in Moore or purposefully ignored them, because he made a P.R. statement concerning Moore’s involvement in the V for Vendetta film that backfired on the production big time.

It took 17 years for the film to make it to the big screen. Road House writer Hillary Henkin wrote a draft in the early 1990’s that attempted to add Robocop-esque satire into the script (“The Ear,” the audio surveillance branch of the fascist government, is housed in a building shaped like an ear). However, a script done by an unknown pair of brothers found a way to keep the book’s tone yet make it workable as a movie. Luckily, those brothers were named Wachowski, they would have a hit at the end of the decade with The Matrix, and the popularity of that film made the V for Vendetta film a reality.

It took 17 years for the film to make it to the big screen. Road House writer Hillary Henkin wrote a draft in the early 1990’s that attempted to add Robocop-esque satire into the script (“The Ear,” the audio surveillance branch of the fascist government, is housed in a building shaped like an ear). However, a script done by an unknown pair of brothers found a way to keep the book’s tone yet make it workable as a movie. Luckily, those brothers were named Wachowski, they would have a hit at the end of the decade with The Matrix, and the popularity of that film made the V for Vendetta film a reality.

Larry Wachowski tried to consult with Moore on the project only to be politely rebuked. “I explained to him that I’d had some bad experiences in Hollywood,” Mr. Moore said. “I didn’t want any input in it, didn’t want to see it and didn’t want to meet him to have coffee and talk about ideas for the film.” Whether or not this was what Larry heard or if he told any of this to Silver is a mystery, because during a March 4, 2005 press conference, Silver told the world that Moore was, “very excited about what Larry had to say and Larry sent the script, so we hope to see him sometime before we’re in the U.K.” In essence, Silver intimated that Moore was on board with the project.

Larry Wachowski tried to consult with Moore on the project only to be politely rebuked. “I explained to him that I’d had some bad experiences in Hollywood,” Mr. Moore said. “I didn’t want any input in it, didn’t want to see it and didn’t want to meet him to have coffee and talk about ideas for the film.” Whether or not this was what Larry heard or if he told any of this to Silver is a mystery, because during a March 4, 2005 press conference, Silver told the world that Moore was, “very excited about what Larry had to say and Larry sent the script, so we hope to see him sometime before we’re in the U.K.” In essence, Silver intimated that Moore was on board with the project.

Moore was incensed. As we explained last time, Moore was once again in DC’s employ after they bought out the publisher he was working for, Wildstorm. He was nearing the end of his contractually mandated work, and seemed to be open to signing on for more. When the Silver statement hit, Moore demanded DC ask their parent company Warner Brothers (the studio releasing the V for Vendetta film) to issue a public retraction. Warners refused, so Moore asked the company to take his name off not only the film but also any Moore books that DC kept in print. He fulfilled the rest of his contract, completing the 19 pages left to do on the titles he was obligated to finish, then he took The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen to Top Shelf, and vowed never to work for DC Comics again. Oh, he also bad mouthed the film every chance he got, calling the film’s script “rubbish” and “imbecilic.” Silver might have thought that he was calming fans fears by hinting that Moore was gung-ho for the project, but what he ended up with was quite the opposite—the creator coming out and viciously savaging the adaptation of his work. Not the best P.R., if you ask me.

I have to say that I share a different opinion of the film than Alan Moore does (or would if he’d actually agree to see it). This is probably bordering on sacrilege, but I consider the film to be better than the graphic novel. The comic is definitely a project born in Thatcher’s England. And while Reagan’s America might have had a number of similarities, there was something lost in the translation. It was hard to completely connect to it on a visceral level.

I have to say that I share a different opinion of the film than Alan Moore does (or would if he’d actually agree to see it). This is probably bordering on sacrilege, but I consider the film to be better than the graphic novel. The comic is definitely a project born in Thatcher’s England. And while Reagan’s America might have had a number of similarities, there was something lost in the translation. It was hard to completely connect to it on a visceral level.

The film, on the other hand, is more universal. It is helped by the fact that it was released into a post-9/11 world, one where the U.S. was torturing terrorism suspects and asking its citizens to forsake their civil liberties in the name of safety. It was a world where there were cameras on the streets of London to monitor the populace’s every move. And it was a world where a lot of countries had media that were the mouth of the government. When we see these elements mirrored in the film, it becomes more real to us.

Next time, we’ll wrap up our look at Alan Moore with the controversy and long path to the big screen of his greatest work—Watchmen.