In a multi-part series, Comic Book Film Editor William Gatevackes will be tracing the history of comic book movies from the earliest days of the film serials to today’s big blockbusters and beyond. Along with the history lesson, Bill will be covering some of the most prominent comic book films over the years and why they were so special. Today, we profile Alan Moore and take a look at film adaptations of his work.

There are a lot of legends in comic books—Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Will Eisner. They have decades of experience in the medium, are considered the founding fathers of it, and have left an indelible mark on comic book history.

If you were nominating Alan Moore for legend-hood due to his work experience, he might not make it. After all, he only has 35 years of experience making comics, half what Stan Lee has. But if you examine his impact on comics, his legendary status will be confirmed. He was one of the first British writers to work for an American comic book company, opening the doors for his fellow countrymen such as Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison and others. His writing has elevated the comic book medium from a place where only kids and simple adults could find reading pleasure to the level of fine literature. He has created some of the best comics the medium has ever known and will ever know. He is a groundbreaking talent, one that has changed the medium he worked in forever.

If you were nominating Alan Moore for legend-hood due to his work experience, he might not make it. After all, he only has 35 years of experience making comics, half what Stan Lee has. But if you examine his impact on comics, his legendary status will be confirmed. He was one of the first British writers to work for an American comic book company, opening the doors for his fellow countrymen such as Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison and others. His writing has elevated the comic book medium from a place where only kids and simple adults could find reading pleasure to the level of fine literature. He has created some of the best comics the medium has ever known and will ever know. He is a groundbreaking talent, one that has changed the medium he worked in forever.

But Moore is just as legendary for his mercurial nature as he is for his creativity. His principles have led him to not only burn bridges, but also nuke them and then urinate on the radioactive ashes. If you want to get an idea of this quality in Moore, all you have to do is look at how his relationship with Hollywood developed over the years. As talented as Moore is, it was only natural that his works would capture the attention of Hollywood. Numerous producers came to make films based on Moore’s work, but most of the efforts left a sour taste in writer’s mouth, and caused him to strike back virulently and publicly.

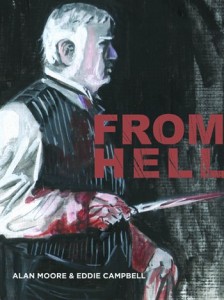

The first work of Alan Moore’s that was brought to the screen was 2001’s From Hell. The film was based on one of the first works Moore created after he left DC Comics due to issues to the rights to Watchmen, royalties from merchandise (I talk more about this in the future) and DC’s implementation of a new rating system. From Hell first appeared in serial form in 1991 in Taboo, an anthology edited by Steven R. Bissette (Bissette was one of the artists on the book that made Moore’s name in the states, Swamp Thing). The story outlasted Bissette’s company, Spiderbaby Grafix, and moved on to Kevin Eastman’s Tundra Publishing before it was completed at Kitchen Sink Comics in 1996.

The first work of Alan Moore’s that was brought to the screen was 2001’s From Hell. The film was based on one of the first works Moore created after he left DC Comics due to issues to the rights to Watchmen, royalties from merchandise (I talk more about this in the future) and DC’s implementation of a new rating system. From Hell first appeared in serial form in 1991 in Taboo, an anthology edited by Steven R. Bissette (Bissette was one of the artists on the book that made Moore’s name in the states, Swamp Thing). The story outlasted Bissette’s company, Spiderbaby Grafix, and moved on to Kevin Eastman’s Tundra Publishing before it was completed at Kitchen Sink Comics in 1996.

On the surface, the comic was Moore’s examination of a pervasive rumor concerning the true identity of Jack the Ripper (that Jack was Queen Victoria’s personal physician, Sir William Gull, who killed the prostitutes of London’s East End to cover up the fact that the Queen’s grandson, Prince Albert Victor, fathered a child with one of their number). But Moore added layer after complex layer to the tale until it became a multifaceted examination of the Victorian Era of England, class struggles between the haves and have nots, sexuality, misogyny, secret societies, an esoteric idea of time as an abstract, and the nature of the unsolved crimes to inspire conspiracy after conspiracy.

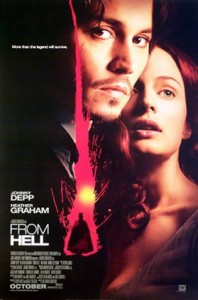

The film sacrifices much of Moore’s subtext and replaces it with a lush visual style and a romance and nasty opium addiction for the lead character. It was directed by the Hughes Brothers, whose prior films were the urban crime dramas Menace II Society and Dead Presidents, and starred a pre-Jack Sparrow Johnny Depp as a much younger version of the graphic novel’s Adderline and Heather Graham as Mary Kelly, one of Jack’s final victims.

The film sacrifices much of Moore’s subtext and replaces it with a lush visual style and a romance and nasty opium addiction for the lead character. It was directed by the Hughes Brothers, whose prior films were the urban crime dramas Menace II Society and Dead Presidents, and starred a pre-Jack Sparrow Johnny Depp as a much younger version of the graphic novel’s Adderline and Heather Graham as Mary Kelly, one of Jack’s final victims.

As it stands, I didn’t think the film was that bad, but without all the subtlety and facets Moore added to the comic, it was little more than just another version of the Jack the Ripper story. But Moore was rather pleasant towards the film in a 2002 interview with The Guardian: “I haven’t seen the From Hell movie yet. I might see it when it comes out on video. I kind of figured from the outset that it wasn’t really fair of me to expect the film to be anything like my book. I’ve tried to keep an emotional distance.”

He’d really have a reason to keep an emotional distance with his next film, where his involvement with film adaptations of his work would really turn sour.

Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen was a unique work from the writer, one that would be steeped in controversy almost from the outset. Originally developed for the Image Comics imprint, Wildstorm, it soon came under the auspices of Moore’s nemesis DC Comics when DC bought Wildstorm from its owner, Jim Lee. Moore agreed to keep LOEG, and other books he created for Wildstorm, going only if Lee promised DC would keep their hands off his work.

Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen was a unique work from the writer, one that would be steeped in controversy almost from the outset. Originally developed for the Image Comics imprint, Wildstorm, it soon came under the auspices of Moore’s nemesis DC Comics when DC bought Wildstorm from its owner, Jim Lee. Moore agreed to keep LOEG, and other books he created for Wildstorm, going only if Lee promised DC would keep their hands off his work.

Moore took a handful of public domain characters from the Victorian era (The Invisible Man, Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde, Allan Quartermain, Mina Murray from Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Captain Nemo from 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea) and joined them together to form a team of adventurers. Over the course of the series, Moore would mine the world of Victorian popular culture for characters for his epic, and would later turn to pastiches of non-public domain characters (for instance, an arrogant spy named only Jimmy is obviously a stand-in for James Bond, and the latest book in the series, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Volume III: Century 2009, ends with a thinly-veiled version of Mary Poppins fighting a thinly-veiled version of Harry Potter for the fate of the universe) to build his world.

The series would feature copious amounts of back matter intricately researched by Moore, be it prose stories written in the style of the era the comic was set in or period advertisements from that same era. One ad in particular caused problems between Moore and DC Comics. Moore ran an ad for a “Marvel Douche” in the fifth issue of the first volume of LOEG. DC, fearing that  competitor Marvel Comics would take offense to the ad, scrapped the print run of that issue and reprinted it without the offending advertisement. Moore saw this as a violation of the “hands off” agreement he made with Lee, and it, coupled with other disagreements with DC and Warner Brothers (including a major dust up over the film version of V for Vendetta that we’ll cover in the next installment) caused Moore to relocate the LOEG franchise to Top Shelf Comics, where it resides today.

competitor Marvel Comics would take offense to the ad, scrapped the print run of that issue and reprinted it without the offending advertisement. Moore saw this as a violation of the “hands off” agreement he made with Lee, and it, coupled with other disagreements with DC and Warner Brothers (including a major dust up over the film version of V for Vendetta that we’ll cover in the next installment) caused Moore to relocate the LOEG franchise to Top Shelf Comics, where it resides today.

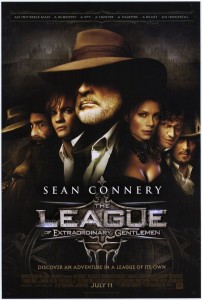

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, the comic book, was a finely detailed and intricately woven piece of fiction by Moore that allowed him to explore and comment on popular entertainment from the Victorian age until the present. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, the film, was not. The best analogy I can come up with is if you took a Rembrandt to your local house painter and asked them to replicate it. At best, you’d get a recognizable, if crude, copy with many of the nuances and subtleties lost. At worst, you’d get a slapdash series of brushstrokes that barely resembles the original. The film falls somewhere in between those two examples.

This isn’t to say that it is a bad thing. Once you get past the fact that it is a supremely dumbed-down version of the highly intelligent original work and some of the more absurd plot points (there is an “automobile” chase through the “streets” of Venice, Italy. Think about that for a second. Let it marinate…), you have something that could be enjoyed as purely brainless fun. Written by James Robinson (himself a British comic book writer who worked for DC Comics) and directed by Stephen Norrington, with copious amounts of studio interference along the way, the film would add two new literary heroes to the cast—Dorian Grey and Tom Sawyer—and a whole lot more action and set pieces. It’s not a great film by any means, and considering the legendary back-biting between director Norrington and star Sean Connery it never could be, but I liked it better than many of the other critics in the world did.

This isn’t to say that it is a bad thing. Once you get past the fact that it is a supremely dumbed-down version of the highly intelligent original work and some of the more absurd plot points (there is an “automobile” chase through the “streets” of Venice, Italy. Think about that for a second. Let it marinate…), you have something that could be enjoyed as purely brainless fun. Written by James Robinson (himself a British comic book writer who worked for DC Comics) and directed by Stephen Norrington, with copious amounts of studio interference along the way, the film would add two new literary heroes to the cast—Dorian Grey and Tom Sawyer—and a whole lot more action and set pieces. It’s not a great film by any means, and considering the legendary back-biting between director Norrington and star Sean Connery it never could be, but I liked it better than many of the other critics in the world did.

While the film made $100 million more than its production budget worldwide, a sequel would never come. Fox was sued by Larry Cohen and Martin Poll, who claimed that they had tried to sell the studio a similarly-themed concept called “Cast of Characters” several years prior.

One of the accusations in Cohen and Poll’s suit was that Alan Moore was commissioned by Fox to write a LOEG comic book based on the pair’s idea so the studio could option the concept from Moore’s work, leaving Cohen and Poll in the lurch. This dragged Moore into legal proceedings he wanted no part of. He described the process in a 2006 interview with the New York Times as such:

“Mr. Moore found the accusations deeply insulting, and the 10 hours of testimony he was compelled to give, via video link, even more so. “If I had raped and murdered a schoolbus full of retarded children after selling them heroin,” he said, “I doubt that I would have been cross-examined for 10 hours.””

Adding another layer of insult to Moore’s indignity was the fact that Fox settled the suit out of court, essentially taking away Moore’s ability to clear his name in a court of law. This was the final straw for Hollywood as far as Moore was concern. He would disparage the Hollywood experience whenever he could, leading to a war of words with LXG & From Hell’s Don Murphy, a war the producer was quite willing to continue for years afterward on various Internet message boards. Moore would no longer allow any of the works he owned to be adapted to the screen, and those he had no say in their adaptation, he would not lend his name or support to.

Adding another layer of insult to Moore’s indignity was the fact that Fox settled the suit out of court, essentially taking away Moore’s ability to clear his name in a court of law. This was the final straw for Hollywood as far as Moore was concern. He would disparage the Hollywood experience whenever he could, leading to a war of words with LXG & From Hell’s Don Murphy, a war the producer was quite willing to continue for years afterward on various Internet message boards. Moore would no longer allow any of the works he owned to be adapted to the screen, and those he had no say in their adaptation, he would not lend his name or support to.

If the producers of V for Vendetta took him at his word, a major brouhaha would have been avoided. We’ll talk about that in our next installment.