In a multi-part series, Comic Book Film Editor William Gatevackes will be tracing the history of comic book movies from the earliest days of the film serials to today’s big blockbusters and beyond. Along with the history lesson, Bill will be covering some of the most prominent comic book films over the years and why they were so special. Today, we discuss the X-Men and why it was miraculous that it made it to the big screen at all.

Today, the X-Men franchise is one of the biggest properties both in comics and in film. But it wasn’t always this way. As a matter of fact, the X-Men were almost a forgotten concept by 1973, just ten years after their creation.

The team were created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in 1963, and arrived on newsstands the same month that Marvel debuted The Avengers. Stan Lee claims that he came up with genetic mutation for the source of their powers because he simply didn’t want to think up another reason for their origin. If this is the case, Lee is an accidental genius. The fact that the heroes of the X-Men had to hid who they really are for fear of being shunned or ridiculed tapped a vein for readers who could easily relate, be they part of the civil rights movement, the gay rights movement, or just plain, old, everyday teenagers. Lee’s choice of an origin for the X-Men opened up an audience for the characters that they wouldn’t have had if they gained their powers through a spider bite or nuclear accident.

The team were created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in 1963, and arrived on newsstands the same month that Marvel debuted The Avengers. Stan Lee claims that he came up with genetic mutation for the source of their powers because he simply didn’t want to think up another reason for their origin. If this is the case, Lee is an accidental genius. The fact that the heroes of the X-Men had to hid who they really are for fear of being shunned or ridiculed tapped a vein for readers who could easily relate, be they part of the civil rights movement, the gay rights movement, or just plain, old, everyday teenagers. Lee’s choice of an origin for the X-Men opened up an audience for the characters that they wouldn’t have had if they gained their powers through a spider bite or nuclear accident.

But even though the X-men had a built in audience, it took a long time for that audience to find the book. Almost from the very beginning, the book floundered. Kirby left after issue #11, leaving the art in the hands of the rather underwhelming Werner Roth. Lee left after issue #19, turning over writing duties to Roy Thomas. The team kept the same staid yellow and blue costumes until issue #39. While the Fantastic Four was facing off against legendary villains such as Galactus and Annihilus and the Avengers were squaring off with Ultron and Kang, the X-Men’s rogue gallery featured such boring entries as the alien Lucifer, Locust, El Tigre and Eric the Red.

The title was in such dire straits that even the addition of superstar artist Neal Adams in 1969 for a seven issue run couldn’t save it from being cancelled. The X-Men went on hiatus with issue #66. It would return eight months later, but only as a bi-monthly reprint title.

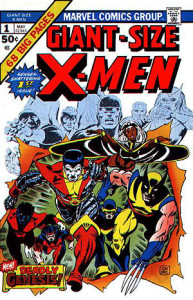

It remained that way until April of 1975 when Giant-Size X-Men #1 came out. Len Wein and Dave Cockrum, working from an idea contributed by former writer Roy Thomas, did a total overhaul of the X-Men. Gone was the chummy, schoolyard camaraderie of the previous team. The “All-New, All-Different” X-men were an international team of adults, each with more issues than National Geographic Magazine. You had pre-existing X-Men villains in the relatively laid back Irishman Banshee and the haughty and arrogant Japanese Sunfire. You had new characters such as the African Storm, who was accustomed to being worshiped as a goddess, and the Native American Thunderbird, the one with a chip constantly on his shoulder. By comparison, two other new characters that should have been reviled became the most identifiable. The German Nightcrawler looked like a demon from the pits of Hell, complete with a pointy tail, yet was playful and gregarious (and also a devout Catholic). And it would have been easy to make the Russian character the least popular one on the team, since it was the heart of the Cold War. But Colossus was a simple farmer with skin of steel and a heart of gold, who was more concerned with painting pretty pictures than spewing Communist Party rhetoric.

It remained that way until April of 1975 when Giant-Size X-Men #1 came out. Len Wein and Dave Cockrum, working from an idea contributed by former writer Roy Thomas, did a total overhaul of the X-Men. Gone was the chummy, schoolyard camaraderie of the previous team. The “All-New, All-Different” X-men were an international team of adults, each with more issues than National Geographic Magazine. You had pre-existing X-Men villains in the relatively laid back Irishman Banshee and the haughty and arrogant Japanese Sunfire. You had new characters such as the African Storm, who was accustomed to being worshiped as a goddess, and the Native American Thunderbird, the one with a chip constantly on his shoulder. By comparison, two other new characters that should have been reviled became the most identifiable. The German Nightcrawler looked like a demon from the pits of Hell, complete with a pointy tail, yet was playful and gregarious (and also a devout Catholic). And it would have been easy to make the Russian character the least popular one on the team, since it was the heart of the Cold War. But Colossus was a simple farmer with skin of steel and a heart of gold, who was more concerned with painting pretty pictures than spewing Communist Party rhetoric.

And the last member of the group? A minor character Wein created several months before in the pages of Incredible Hulk. A diminutive Canadian named Wolverine.

This was not the X-Men team you read when you were a child. And when Thunderbird became the first member of the team to die in action six months later in issue #95 of the restarted X-Men series, it became clear anything could happen.

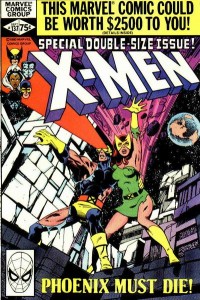

Wein eventually made way for Chris Claremont as writer, and Claremont’s writing brought new fans in. Claremont took the team from a bunch of combative character flaws to a group of noble souls with their own vulnerabilities and quirks. He humanized the mutantsand played up the “oppressed minority” aspect more than it ever hd been, tasks that went even farther once Claremont was joined by John Byrne as penciller and co-plotter a year and a half later. Claremont and Byrne had an explosive synergy, quickly becoming one of the most renown creative teams in comics, creating such legendary story arcs as the Hellfire Saga (briefly touched on in X-Men: First Class), the Dark Phoenix Saga (which became part of X-Men: The Last Stand‘s plot) and Days of Future Past (which inspired the forthcoming X-Men: Days of Future Past).

Wein eventually made way for Chris Claremont as writer, and Claremont’s writing brought new fans in. Claremont took the team from a bunch of combative character flaws to a group of noble souls with their own vulnerabilities and quirks. He humanized the mutantsand played up the “oppressed minority” aspect more than it ever hd been, tasks that went even farther once Claremont was joined by John Byrne as penciller and co-plotter a year and a half later. Claremont and Byrne had an explosive synergy, quickly becoming one of the most renown creative teams in comics, creating such legendary story arcs as the Hellfire Saga (briefly touched on in X-Men: First Class), the Dark Phoenix Saga (which became part of X-Men: The Last Stand‘s plot) and Days of Future Past (which inspired the forthcoming X-Men: Days of Future Past).

By the time Byrne left the book in December 1980, the X-Men were well on their way to becoming the most successful book Marvel published. It would spawn numerous spin-off titles, quite a few crossover events, and help launch the careers of artists such as Jim Lee and Marc Silvestri. And with that success came some attention from Hollywood. As early as 1984, Hollywood had plans to make an X-Men film, which would have made it the Marvel’s earliest entry onto the silver screen.

Roy Thomas and fellow comic book scribe Gerry Conway were hired to write the screenplay for a potential X-Men film for Orion Films. Their film features a different take on X-Men comic book villain Proteus as the main bad guy (instead of a reality warping mutant, it was an organization ran by a vampire-like mutant named Stonewall). The word mutant is never used in the script. The team consisted of Wolverine, Storm, Nightcrawler, Colossus, an ambulatory Professor Xavier, Cyclops, Kitty Pryde, and a Japanese pop star named Circe who can transmute matter. Orion entered financial difficulties soon after the script was written, and had the back out of the project. Conway and Thomas’ script was shopped around, but with no takers.

Roy Thomas and fellow comic book scribe Gerry Conway were hired to write the screenplay for a potential X-Men film for Orion Films. Their film features a different take on X-Men comic book villain Proteus as the main bad guy (instead of a reality warping mutant, it was an organization ran by a vampire-like mutant named Stonewall). The word mutant is never used in the script. The team consisted of Wolverine, Storm, Nightcrawler, Colossus, an ambulatory Professor Xavier, Cyclops, Kitty Pryde, and a Japanese pop star named Circe who can transmute matter. Orion entered financial difficulties soon after the script was written, and had the back out of the project. Conway and Thomas’ script was shopped around, but with no takers.

Five years later, Stan Lee, Chris Claremont and James Cameron were in negotiations with Carolco Pictures in order to get an X-Men film made. Once again, the studio’s insolvency cause the X-Men film to be dropped. Cameron went on to focus his attention on getting a Spider-Man film made, which we’ll talk about a bit later.

It seemed like the X-Men film was cursed to go to one financially plagued studio to another, yet never being made. But the property’s success in the world of Saturday morning cartoons caused a major studio to take interest. We’ll discuss that next time.

Bill Thomas liked this on Facebook.

FilmBuffOnLine liked this on Facebook.