Note the wording: Geek directors who TRULY LOVE the source material. To show the difference in superhero film eras, he says this about the first go round for Batman:

Compare that to 1989’s Batman, directed by a guy who said he didn’t like comics and written by a guy who thought Batman’s origin story was too dumb to work in a movie. It was a new era. The geeks had ascended to the throne!

Okay, back to the list!

7. Tim Burton never said he didn’t like comics.

Sargent employs the kind of journalistic skills you’d find in the New York Post, the National Enquirer, and on Fox News here–twisting a person’s words around to fit your own desired meaning. Sargent uses the book Burton on Burton for the source on that information. Let’s see what the paragraph Sargent got that quote from really says:

What Burton really said was that he was never a comic book fan, not that he didn’t like comics. There IS a difference. This is dirty pool by Sargent. He is definitely trying to give his readers the impression that Burton hated comic books. It really doesn’t seem that way. And as explained above, it was because there was a learning curve he couldn’t get by. It wasn’t until Alan Moore’s The Killing Joke comic came along was he able to figure out how to read comics. And he loved that comic book.

What Burton really said was that he was never a comic book fan, not that he didn’t like comics. There IS a difference. This is dirty pool by Sargent. He is definitely trying to give his readers the impression that Burton hated comic books. It really doesn’t seem that way. And as explained above, it was because there was a learning curve he couldn’t get by. It wasn’t until Alan Moore’s The Killing Joke comic came along was he able to figure out how to read comics. And he loved that comic book.

8. And he misquotes Sam Hamm too.

“You totally destroy your credibility if you show the literal process by which Bruce Wayne becomes Batman,” said Sam Hamm, screenwriter of the 1989 Batman.

That is the quote that Sargent uses as a source. It was published in a Digital Spy recap of the Batman franchise, surely taken from a Cinemafantastique interview done with Hamm back when Batman first came out. As you can see, Hamm doesn’t call Batman’s origin dumb. He isn’t even talking about Batman’s whole origin. Bruce Wayne’s parents still get gunned down in front of him in the film, so that part of the origins still exists. Hamm was talking about the training part of the origin, the part that Batman Begins did so well. Nowhere in that quote does Hamm say the origin was dumb. It seems pretty obvious that he’s saying that it wouldn’t work in the version of Batman Burton was putting on the screen at the time.

But he doesn’t have to mislead his readers about the current generation of comic book film makers, does he? Every last one of them”TRULY LOVE” the source material, right?

Wrong.

9. By the way, Bryan Singer? The director of X-Men? The film that Sargent says started the Superhero film trend? Not a life-long comic book fan.

From the X-Men panel at the 2000 San Diego Comic Con, transcribed by JoBlo:

How long have you been reading the X-Men comics, or comics in general? Have you always been a fan? Seems to be that you would have to be to get it all so right.

Well, as a matter of fact…<audience laughs>, I never read comics growing up at all. I liked science-fiction, fantasy, and watched a lot of television, but I never read comics. About three and a half years ago, Tom suggested that I take a look at X-Men, I did, and I found it incredibly fascinating, so I began to read, began to read the character biographies, began to read the comics, I watched all 70 episodes of the animated series, and really familiarized myself. So basically I’ve been reading X-Men for about three and a half years, but I’m much more of a contemporary fan.

10. Christopher Nolan? He wasn’t a comic fan either.

From an Entertainment Weekly profile from 2005, right when Batman Begins was about to hit:

But Nolan had never been a big Bat geek; his first contact with the series had been the goofy Adam West TV show, and he’d never read the comics as a kid.

So, that means two of the biggest names in the superhero film renaissance, who according to Sargent’s theory truly loved the source material and made sure they brought it to the screen correctly, had at best a casual, if passing, knowledge of source material before they took over. Yet another hole shot in Sargent’s argument.

Wait! Sargent seems to realize this, because he gives Nolan an out in the third reason “The Studios Start Throwing ALL of the Money at Them,” which really an extension of the previous reason but since all Cracked articles have to have at least five bullet points, they had to make two reasons out of one idea. But I digress:

Nolan talks about being passionate about the character (one of the hallmarks of Nerdywood, as explained above), and he had a weird, borderline crazy idea for the new series: Batman would be gritty and realistic.

Being passionate about a character is greater than truly loving the source material. Unless, of course, you are Tim Burton, because, well, that wouldn’t fit with the argument you are making, right JF?

We’ll get back to reason three later. Let’s go back reason two, especially how “New Hollywood” relates the now disproved idea that hardcore comic geeks were behind all the new comic book movies.

The New Hollywood era was all about film geeks taking over — a bunch of weird, experimental directors known as the “movie brats,” with names like George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, and Stanley Kubrick.

11. Stanley Kubrick really wasn’t part of New Hollywood.

Now, this isn’t the fault of Sargent, but rather the Wikipedia article that acted as his inspiration. And they really aren’t at fault either. Everyone thinks that trying to pigeonhole a certain period time and applying a name to it is a good idea. But it is never a case of black and white, rather it’s a shade of gray. Sargent’s theorem works if New Hollywood era lasted 13 years from inception to demise because we are at year 13 in the superhero era (if you count X-Men as the start of it, which I don’t). However, it’s impossible to get anything so fluid and so debatable into those kind of constraints.

Now, this isn’t the fault of Sargent, but rather the Wikipedia article that acted as his inspiration. And they really aren’t at fault either. Everyone thinks that trying to pigeonhole a certain period time and applying a name to it is a good idea. But it is never a case of black and white, rather it’s a shade of gray. Sargent’s theorem works if New Hollywood era lasted 13 years from inception to demise because we are at year 13 in the superhero era (if you count X-Men as the start of it, which I don’t). However, it’s impossible to get anything so fluid and so debatable into those kind of constraints.

New Hollywood has an veneer of youth to it. The recent film school grads got their hands on the directors chairs and guided Hollywood to a new direction. However, Kubrick was already a 14 year veteran of the film industry when Bonnie and Clyde arrived in 1967, had made seven films by that point, and had already received Oscar nominations for Best Director and Best Screenplay. Granted, 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey was a transcendent piece of work in Kubrick’s career, but you can see hints of where Kubrick was going in 1962’s Lolita and 1964’s Dr. Strangelove. His creativity and willingness to push boundaries does seem to be a perfect match for some of the other auteurs on the New Hollywood list, but he was anything but new when New Hollywood hit.

Let’s go on to his third point (the “Throwing ALL the Money” one, although the throwing of money is barely mentioned). In it, he brings up the theme of risks. First about Nolan’s grim and gritty take on Batman:

That had never been done on film before, but Nolan was young, nerdy, and excited, so the studios gave him an insane-o-copter ride to the money castle, and holy shit did it ever pay off.

Then he tries to convince us that The Avengers was risky. Hee hee!

Fast forward 10 years, and you can see that The Avengers is pretty much the same thing, except even more so. No, it’s not gritty or realistic, but it sure is weird and risky: It expects audiences to follow one story across two sci-fi action movies, a fantasy movie, a fugitive movie, and a World War II era adventure film. Most movies treat you like you can’t even tie your own goddamn shoes, but The Avengers took that risk and ended up going home with 1.5 billion nerd-dollars lining its pockets.

Let’s go in order, shall we?

12. The gritty, realistic Batman wasn’t risky, it was wish fulfillment.

The comic book Batman has been grim and gritty since 1986, when the Batman: The Dark Knight Returns miniseries began publication. While it is true that every version of Batman in other media before Nolan took the edge off the character, the hardcore fans would have actually preferred an interpretation of the Caped Crusader that matched more with his comic book counterpart. When one of the most exciting directors in Hollywood teamed with a screenwriter with comic book experience to bring a Batman to the screen that had more in common with The French Connection than Schumacher’s nipple fest, well, fans were salivating. Add to that a cast that would be chock full of Oscar winners and nominees, and you had the makings of a sure fire hit before the first showtime was announced.

And…

13. What Sargent thinks made The Avengers risky, is what guaranteed its success.

Sargent apparently never heard of the concept of a sequel. Or of the Harry Potter franchise. Because The Avengers essentially was a sequel to all those films listed. You didn’t really have to see all those films to get enjoy The Avengers. But if you enjoyed Captain America: The First Avenger or Thor, you had a chance to continue watching his adventures. You had four pre-fab audiences built in.

But if you did see all the films, you had the culmination of a sweeping epic in The Avengers. Movie audiences are not so stubborn as to not follow a franchise through numerous installments, and the James Bond, Harry Potter, and Twilight franchises have showed us. But, hey, if Sargent actually paid attention to this reality, he wouldn’t have had a column.

Sargent felt he needed to manufacture risks for the superhero films to make the connection with the real risks the New Hollywood films endured:

Coppola’s Apocalypse Now was a weird, morally complicated exploration of war based on a nigh-impenetrable 19th century novel, but it dominated the box office. Jaws was the first ever summer blockbuster, and Star Wars only turned out the way it did because Lucas refused to compromise and made the movie himself.

The first two also had incredibly tumultuous shoots and faced having the studio pulling the plug a number of times. And the studio was so worried about Star Wars‘ success that Lucas went and practically begged Marvel to publish a comic book tie-in to the film as an extra form of promotion. So the risk in the New Hollywood era were indeed real. This won’t be the last time the eras don’t exactly match up.

Sargent moves onto the next step of the rise and fall of these genres–studios taking more control of their film projects. It’s here where the parallels between the New Hollywood era and the Superhero film era start to really waiver, because the evidence Sargent presents is definitely in favor of the Superhero era:

You could start to see the signs years ago. After the success of Raimi’s first two Spider-Man movies, the studio pressured him into including Venom because he was a popular comic book character — except Raimi had been concentrating on the Silver Age of comics, and the dark, gritty, ’90s era Venom didn’t fit into the world he’d created. When they greenlit a movie version of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, they had such a limited idea of what a comic book movie could be that they turned Alan Moore’s love letter to 19th century prose into a movie with vampires where things explode and Sean Connery does hero things. When they made The Losers, they cut out all the political commentary and replaced it with light-hearted action bullshit. When they made Watchmen, they cut out the self-loathing, rape, and moral complexity and replaced them with slow-motion action scenes. As other people have pointed out, this totally missed the point that Watchmen is about failure.

On this point I do have to agree with Sargent. I do think that undue studio influence does ruin a lot of films. However…

14. Heavy handed studio/producer involvement is nothing new to comic book films…

Tim Burton has to wrangle with his studio bosses during his time on Batman. Richard Donner fought with the Salkinds over the tone of Superman. The reason why the Superman franchise took so long to be rebooted was because various producers wanted the film to include giant spiders or mimic The Matrix. So, this kind of heavy-handedness is nothing new.

15….nor is it exclusive to the comic book films.

Studios insisted that Blade Runner have a happier ending. Universal wanted a happy, 94-minute version of Brazil and got in a war of wills with Terry Gilliam over it. And studio influence handcuffed The Bonfire of the Vanities from the get go, coercing Brian DePalma to cast Bruce Willis and make Sherman McCoy a more sympathetic character. And these are just three examples. There are many, many more (although Sargent has problems finding any during the New Hollywood era).

16. However, if it wasn’t for Marvel playing a bigger role in the creation of their films, the Superhero era might not have even existed.

It fits Sargent’s narrative if Marvel just recently started becoming more hands on (after all, it was Marvel’s Avi Arad who pushed for Venom, not Sony/Columbia), but the truth is the reason why the Superhero era in film began is because Marvel and, in particular, Avi Arad took a hands on role it how Marvel properties would be portrayed on the big screen. The studios would own the rights as long as the kept making movies, and the amount of the profits kicked back to Marvel were paltry, but Arad and other Marvel people would become producers on the films and ensure that the Marvel characters were getting a fair shake on the screen.

It fits Sargent’s narrative if Marvel just recently started becoming more hands on (after all, it was Marvel’s Avi Arad who pushed for Venom, not Sony/Columbia), but the truth is the reason why the Superhero era in film began is because Marvel and, in particular, Avi Arad took a hands on role it how Marvel properties would be portrayed on the big screen. The studios would own the rights as long as the kept making movies, and the amount of the profits kicked back to Marvel were paltry, but Arad and other Marvel people would become producers on the films and ensure that the Marvel characters were getting a fair shake on the screen.

When the first wave of Marvel films became a success, due in a large part to Marvel’s hands on approach, Marvel decided they wanted even more control. Through a deal with Merril Lynch, Marvel received $525 million dollars to set up its own production studio to make comic book films their way. The first of these films was Iron Man and the rest, they say, is history. With their own studio, Marvel was able to guide their film franchises, unite them together through shared actors and plot points, and made sure they respected their source material.

And Marvel’s success inspired Warners to get more serious with their DC Comics properties, rebooting the Superman franchise (twice), the Batman franchise (most likely twice) and try to jump start new franchises with Green Lantern and Jonah Hex. Other studios scoured comic book store shelves for properties they could adapt. And hence the Superhero Film era we are living in today.

I could comment and some of Sargent’s other examples, but I don’t think they are worth a list entry. Yeah, there was studio fingerprints all over League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, but Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill pretty much washed their hands with the property when they got their checks. It’s not like they cared what the studios did with it. I’m not sold on The Losers suffering from studio interference, but any interference was mitigated by director Sylvan White keeping creators Andy Diggle and Jock in the loop. And I think a lot of the things Sargent found missing in the Watchmen are still there, but I agree the slo-mo additions were awful.

When Sargent’s analogy turns to New Hollywood, he comes up with a profound lack of examples, and the one he does use is incorrect. His idea of how studio interference worked in the New Hollywood era was that corporations started buy movie studios looking for the next Jaws or Star Wars, but decided to play it safe with sequels. The one example he gives of this new regime interfering with creative people is this:

But with these massive budgets, studios were determined to play it safe. That meant, of course, some of the riskier directors had to go — like when they were considering giving Straw Dogs director Sam Peckinpah the Superman movie, but fired him when he pulled a gun out during a meeting.

Hoo boy.

17. Sam Peckinpah was NEVER fired from Superman. Why? Because he was never HIRED to do Superman.

I imagine that by the time this point appears, half way down the second page of the article, Sargent figures that he has put enough links in his text that people do not bother to even click through anymore. I mean, why else would he write something that is obviously in contrast to what his source material says.

I imagine that by the time this point appears, half way down the second page of the article, Sargent figures that he has put enough links in his text that people do not bother to even click through anymore. I mean, why else would he write something that is obviously in contrast to what his source material says.

The source is the very good book by Larry Tye, Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero. If you click that link you’ll see that Peckinpah pulled the gun during the Salkinds’ SEARCH for a director. Unless Sargent has a vastly different work experience than the rest of the world, you typically aren’t put on the payroll during your interview period.

I know what some of you might be thinking. Big deal. So he got a word wrong. Who cares? Well, I do for two reasons. This is a writer of such a caliber that Cracked tapped him to their workshop moderator, the person who guides novice comedy writers to Cracked super stardom. His not being able to find a word that accurately portrays the point his source material makes is not a good thing. But this very likely could be just a subtle example of what Sargent has been practicing all along, trying to jury rig a weak argument so that it looks stronger. He’s already in trouble because the examples in both eras don’t even out. Since studio interference weighted more heavily in the Superhero Film era, Sargent needs to show a little balance. Using “fired’ instead of “backed away” is a minor change that makes the studios in the New Hollywood era look more forceful, more controlling, more in charge.

Besides, Peckinpah pulled a gun on a job interview! Even if he was fired, would that really be the wrong choice?

We finally come to the end of the eras, when the bets no longer pay off. Once again, this parallel is a little uneven since the New Hollywood has officially ended and the Superhero Film era is still going on. So Sargent dedicates most of his time talking about the Superhero Film era to showcasing where the end may lie, starting with, well, not a superhero film:

We mentioned that New Line has given Peter Jackson a castle made of money for his Hobbit trilogy, but we didn’t mention that they’re $5 billion in debt and need him to make all that money back to keep themselves from filing for bankruptcy. Is it any wonder that what was originally supposed to be one movie got stretched into two movies? And then, very late in production, they decided out of the blue to stretch it into three?

They needed three shots to recoup their investment. That’s why the first film, An Unexpected Journey, was based less on the children’s book it gets its name from and more on The Return of the King‘s appendices and whatever bullshit Tolkien scrawled on the Oxford staff bathroom’s wall while he was fucked up on opium.

18. Bilbo Baggins is no more a superhero than Frodo Baggins.

Page up and read #5 on this list. But, for the sake of argument, let’s play along, shall we?

19. The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey made $1 BILLION worldwide.

That means the trilogy is on pace to make $3 billion. Of course, the sequels could make less or more, we don’t know. Quite a bit less than $5 billion of New Line debt, and New Line has to share the pie with Warner Brothers and MGM, but if you add in all the T-shirts, statues, figures, games, posters and the exorbitant number of home video formats the film was released into, I think it’s a safe bet that The Hobbit won’t capsize the Superhero Film era, even if it was a superhero film.

Next?

But they’re not the only ones putting all of their chips on their geek franchise. In addition to the lineup of 10 massive Marvel sequels we mentioned earlier, you have Christopher Nolan (probably) signing on to “Godfather” a Justice League movie — if you’re not familiar, that means that in addition to the Superman reboot we’re seeing this summer, they’d be launching another wave of superhero movies, including a Green Lantern sequel, a reboot of The Flash, a possible Wonder Woman movie, and God knows what else, in order to have them finally all team up in a Justice League tent-pole that would be the DC version of The Avengers.

How wrong is this paragraph? Let me count the ways:

20. Sargent is using Latino Review’s El Mayimbe as a source.

We here at FilmBuffOnline know in that way madness lies. And, well, wrong information lies there too.

21. The “Nolan Godfathering Justice League” rumor was shot down back on April 11, 2013.

We covered it here. Entertainment Weekly got the denials straight from Warners’ president Jeff Robinov and Nolan’s reps. Besides, Nolan is working on a non-Superhero movie of his own, Interstellar, which will probably dominate all of his “godfathering” time.

22. Warner Brothers has been ultra quiet on the Green Lantern sequel.

They announced that a sequel was definitely in the works right after the first Green Lantern came out. There has not been any movement on the sequel at all since that time. Except for rumors that Ryan Reynolds might not even becoming back.

23. A Flash movie would be rebooting what exactly?

This might just be a matter of semantics, but if Sargent means the Flash TV show, then he’s off base. When a TV show moves to the big screen, it’s not being rebooted. It’s being adapted into another medium. But Sargent likes his reboots, so, there you go.

24. It much more likely that Wonder Woman would be a TV show before it becomes a movie.

Warners is actively developing a Wonder Woman TV show, called Amazon, in the mold of its successful Smallville and Arrow series’. Not that this would preclude a film being made, but all energy seems to be heading towards that.

25. As it stands, Warners plans to have the Justice League film first, and use that to spin out solo superhero films, not the other way around.

This is pretty much common knowledge. Last we heard, Justice League was set for a 2015 release. Common sense dictates that Warners would not be able to put up three other superhero films before that time, especially since zero work has been started on any of them. Now, it appears the greenlight for the JL film is on hold until the studio sees how Man of Steel does, and there is supposedly a big announcement forthcoming from Warners about their superhero slate, so this might all change. But, as it stands, it’s Justice League first, other films later, and Sargent is wrong (again).

26. Lord knows if DC will get their act together in time to avoid the comic film apocalypse.

Seriously, the only comic film they have confirmed to be in the pipeline is Man of Steel. And that took years to get up and running. It’s Warners’ M.O. to have let their comic book film linger in development hell. If this is the end of the Superhero Film era, Warners most likely won’t be the reason why it dies, but rather they will be the ones who missed the boat because it did.

Next?

Meanwhile, J.J. Abrams, who is already in charge of the new Star Trek franchise, has been tapped to direct the first of the new Star Wars sequels, of which there will be at least five –– three sequels, plus multiple stand-alone spinoffs (Disney wants a new Star Wars movie every single year, like clockwork). How much money in production and promotion do you suppose will be tied up in just the projects we mentioned up there? $10 billion? More?

27. Once again, Star Wars films are not Superhero films.

You do have to admire Sargent’s ability to set parameters then completely ignore them. But, once again, we’ll play along.

28. If you think a new round of Star Wars films helmed by J.J. Abrams has a snowball’s chance in Hell of failing, you need your head examined.

It appears that JF Sargent doesn’t get out much. If he does, he probably doesn’t spend much time in malls or department stores. He obviously hasn’t seen rows and rows of Star Wars toys in the toy department. He probably hasn’t seen the wide assortment of Star Wars themed clothing on sale in not only the children’s department but also the men’s and women’s departments. He probably has never seen the numerous volumes of Star Wars novels in his local bookstore either. He lives in a blissfully ignorant reality where Star Wars is not the biggest cultural icon to ever come out of Hollywood, and a relentless cash cow for George Lucas for the last 36 years.

It appears that JF Sargent doesn’t get out much. If he does, he probably doesn’t spend much time in malls or department stores. He obviously hasn’t seen rows and rows of Star Wars toys in the toy department. He probably hasn’t seen the wide assortment of Star Wars themed clothing on sale in not only the children’s department but also the men’s and women’s departments. He probably has never seen the numerous volumes of Star Wars novels in his local bookstore either. He lives in a blissfully ignorant reality where Star Wars is not the biggest cultural icon to ever come out of Hollywood, and a relentless cash cow for George Lucas for the last 36 years.

He was probably a wee baby back in 1999 and wasn’t able to fully comprehend the frenzy that existed when The Phantom Menace hit theaters. Even hardcore fans will admit that was the weakest installment of the franchise, yet it still made over a billion dollars worldwide, the fans still came back for two more installments, and those toy stores are still rolling out new action figures based on the film even 14 years later.

So, yeah, Abrams has to drop the ball on an almost apocalyptic level for him to ruin the Star Wars franchise forever and cause the end of any film era it actually fits into. Even if he screws up the next film in the line so badly that Star Wars fans melt the Internet by complaining so much, those same fans will be back for the next go round. And they’ll still buy the toys, the mugs, the sheet sets, the T-Shirts, the window decals and what have you.

Also note that the source he uses for Disney’s Star Wars plans was an article dated April 17, 2013. Which means he should have known the Latino Review rumor wasn’t legit because it was refuted almost a week prior. Unless he just ignored the EW article because it contradicted the narrative he was trying to tell.

Well, that was silly. Now, onto the fall of New Hollywood!

Star Wars and Jaws are called “the beginning of the end” of New Hollywood (by Wikipedia, anyway) because they created the blockbuster, but the real end didn’t come until around 1980, with the release of two legendary flops: Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, and Francis Ford Coppola’s One from the Heart.

29. Star Wars and Jaws went from being a high point of the New Hollywood era just a few paragraphs ago to being the cause of its demise?

That’s what you get when you use Wikipedia as a source unchallenged. Also, when you try to put arbitrary guideposts in effect just to make an “era” line up correctly.

30. One from the Heart actually came out on February 12, 1982.

By this point in Sargent’s argument, we shouldn’t be surprised that he kept this information a secret. After all, it comes after a long line of fact fudging to make his 13/13 argument work. And I guess he deserves partial credit for saying “around 1980” (although the 15 month gap between films stretches the definition of being “around”). But if he doesn’t want us to consider Star Wars and Jaws as the beginning of the end, he shouldn’t be allowed to consider Heaven’s Gate as the beginning of the end just because it suits his purposes. I mean, there were films such as Raging Bull, Body Heat and Reds that came out between Heaven’s Gate and One from the Heart. These are vital films with a lot of success that totally fit in the New Hollywood era, so it wasn’t like there was a parade of dreck that came out between those films.

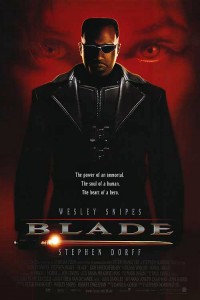

The weird part of all this is, if Sargent just allowed himself to recognize that the Superhero Film era began with 1998’s Blade, he wouldn’t have to be so dodgy with One from the Heart‘s release date. Because instead of a 13/13 parallel, he’d actually have a 15/15 parallel.

31. All you need is two flops to derail an era? May I present to you Punisher: War Zone and The Spirit.

Both films are excellent representations of the Superhero Film era. The first was a reboot of a superhero that had appeared on the silver screen twice before, the most recent only four years before. He was being rebooted to make him more closely resemble how he was portrayed in the comics. The other was a Golden Age character who was being brought to the screen by Frank Miller, who not only was a big name in Hollywood after the surprise film success of his works 300 and Sin City, but also a close friend with Will Eisner, the man who created the character. Miller seemed like the ideal person to bring this superhero to the big screen.

Both films are excellent representations of the Superhero Film era. The first was a reboot of a superhero that had appeared on the silver screen twice before, the most recent only four years before. He was being rebooted to make him more closely resemble how he was portrayed in the comics. The other was a Golden Age character who was being brought to the screen by Frank Miller, who not only was a big name in Hollywood after the surprise film success of his works 300 and Sin City, but also a close friend with Will Eisner, the man who created the character. Miller seemed like the ideal person to bring this superhero to the big screen.

Unlike Sargent’s example, both these film actually did come out in the same year, 2008, and in the same month as a matter of fact. Both died a quick death at the box office, failing to make their budget’s back. And their failure so quickly after each other had even me asking if this was the end for the comic book film.

But the comic book movie didn’t end. The next year started bumpy with the Watchmen, but bounced back with X-Men Origins: Wolverine. 2010 had disappointments with Jonah Hex and Scott Pilgrim Vs. the World, but 2011 and 2012 became some of the biggest years for any comic book film in their history. And despite what Sargent says, there doesn’t seem to be any signs of stopping.

32. You can argue that the “New Hollywood” era never ended.

Granted, it did seem to end for directors such as Michael Cimino, Peter Bogdanovich and even Francis Ford Coppola. But Robert Altman kept making inventive and risky films right up until he died in 2006. Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese went on to win Oscars and keep getting nominations, pushing boundaries and taking risks to this very day. And there are a whole new generation of filmmakers such as Paul Thomas Anderson and Quentin Tarantino who were inspired by the era and keep its spirit alive even now.

I’ll be the first to admit that the one surefire way to get me upset is to write an article predicting doom for the superhero film. But I probably wouldn’t have used as much bandwidth to this article if JF Sargent presented his argument honestly and with valid evidence to back it up. Unfortunately, Sargent starts with a shaky premise for an argument, finds it doesn’t work the way he thought it would, so he cuts corners, fudges facts, and plays fast and loose with the premise until it comes out the way he wants it to be.

I guess we shouldn’t expect great journalism from Cracked. After all, it seems more concerned about generating hits than reporting any truths. But you’d expect better from the guy who is supposed to show the way to the novice writers Cracked attracts. If the Superhero Film era is due to end soon, it won’t be for the reasons JF Sargent says it will.

Granted, the film was shot for $1 million dollars, a sum way under what it would take to make a good FF film. It was cheap and it looked it. But the main factors at play seem to be the ones mentioned above. And Arad’s reason for putting the film on ice, as described on the very Wikipedia page Sargent linked to, seems less about how bad it was, but how little money was spent on it.

Granted, the film was shot for $1 million dollars, a sum way under what it would take to make a good FF film. It was cheap and it looked it. But the main factors at play seem to be the ones mentioned above. And Arad’s reason for putting the film on ice, as described on the very Wikipedia page Sargent linked to, seems less about how bad it was, but how little money was spent on it. If Sargent was looking for a comic book film that fit his analogy to a T, Blade is it. It was the first film where Marvel took a more active role in the production of the film, marking a new attention towards fidelity to the source material that Sargent marks as a trademark of the superhero film era. It was also an unknown property without a huge built in audience, so it was not a lock that it would be a success. But it was, it debuted at #1 at the box office just like Sargent’s other examples and made a sizable profit. If there was a film that ushered in the era of the superhero movie, it was Blade.

If Sargent was looking for a comic book film that fit his analogy to a T, Blade is it. It was the first film where Marvel took a more active role in the production of the film, marking a new attention towards fidelity to the source material that Sargent marks as a trademark of the superhero film era. It was also an unknown property without a huge built in audience, so it was not a lock that it would be a success. But it was, it debuted at #1 at the box office just like Sargent’s other examples and made a sizable profit. If there was a film that ushered in the era of the superhero movie, it was Blade. Second, Sargent intends to show that the 90s were a dry period for the superhero movie. But they really weren’t. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, The Crow, The Mask, and Men in Black all could be considered superhero films (if Frodo’s a superhero, then so is Agent J). They all came from comic books. All their lead characters fought crime in different ways. And all of them were box office hits in the comic book film unfriendly 1990s. Each one had at least one sequel, which is more than you can say for Sargent’s examples. And, lest we for get, Batman Returns, Batman Forever and, yes, Batman and Robin all were released in the 90s and all made a profit (yes, even Batman and Robin, when worldwide grosses are added in).

Second, Sargent intends to show that the 90s were a dry period for the superhero movie. But they really weren’t. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, The Crow, The Mask, and Men in Black all could be considered superhero films (if Frodo’s a superhero, then so is Agent J). They all came from comic books. All their lead characters fought crime in different ways. And all of them were box office hits in the comic book film unfriendly 1990s. Each one had at least one sequel, which is more than you can say for Sargent’s examples. And, lest we for get, Batman Returns, Batman Forever and, yes, Batman and Robin all were released in the 90s and all made a profit (yes, even Batman and Robin, when worldwide grosses are added in).

Oddly enough, the bubble may burst but it has more to do with salaries and RJD jr. than the want for superhero films waning. I am of the impression that the want goes away if we lose the ACTORS folks have grown accustomed to.

[…] Rebutting that Cracked article about superhero movies being a bubble (Film Buff Online) […]