In a multi-part series, Comic Book Film Editor William Gatevackes will be tracing the history of comic book movies from the earliest days of the film serials to today’s big blockbusters and beyond. Along with the history lesson, Bill will be covering some of the most prominent comic book films over the years and why they were so special. This time, we’ll talk about three “superhero” films that offer a bit of metacommentary on comic books and the real world.

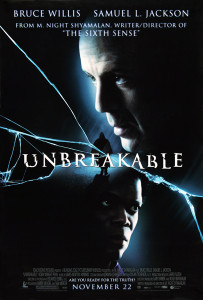

After The Sixth Sense, M. Night Shyamalan could do no wrong. That film was a surprise success, and its twist ending had many people comparing Shyamalan to Alfred Hitchcock in the kindest of terms. All of Hollywood was looking to do business with the director, and they were willing to let him do whatever he wanted.

Fortunately, Shyamalan had written a spec script during post-production of that film, a script that Touchstone Pictures bought for a record-setting $5 million (the most paid to that point for a spec script). Audiences and critics eagerly awaited this new Shyamalan film, expecting it to be a psychological thriller along the lines of The Sixth Sense. What they got was something entirely different.

Unbreakable wasn’t just a superhero movie, but rather a deconstruction of the superhero mythos. It went one step beyond transporting the Superman archetype to a more realistic setting by becoming a quasi-psychological examination of comic book tropes and trademarks.

The film focuses on David Dunn (Bruce Willis), an unemployed security guard who survives a horrific train wreck, one which killed all of the other 131 passengers on the train. Soon after, he is contacted by Elijah Price (Samuel L. Jackson), a comic book fan who believes Dunn is a superhuman come to life. Price leads Dunn down a path of self-discovery, which results in a sinister revelation at the end of the film.

The comic book tropes are all over the film, starting with the protagonist’s alliterative name. David Dunn calls to mind a long line of comic book character’s alter egos (Peter Parker, Bruce Banner, Lois Lane, Lana Lang, Lex Luthor, etc). Much like Superman with Kryptonite and Green Lantern with the color yellow, Dunn finds a weakness that strips him of his powers (It just happens to be water. GL is the butt of many jokes by being able to be neutralized by a banana peel, imagine a superhero who was useless when it rains. Shyamalan reused the weakness for the aliens in Signs, which was even sillier. Why try to conquer a planet that is two-thirds covered in the stuff that can kill you? But I digress…). And Dunn’s arch-enemy is his polar opposite—like Batman, bastion of order, having to tangle with the anarchic Joker, or the physically powerful alien Superman having to constantly fight the intellectually gifted, albeit completely human, Lex Luthor, the indestructible Dunn must contend with a man with a rare bone disease that makes his bones incredibly fragile.

The comic book tropes are all over the film, starting with the protagonist’s alliterative name. David Dunn calls to mind a long line of comic book character’s alter egos (Peter Parker, Bruce Banner, Lois Lane, Lana Lang, Lex Luthor, etc). Much like Superman with Kryptonite and Green Lantern with the color yellow, Dunn finds a weakness that strips him of his powers (It just happens to be water. GL is the butt of many jokes by being able to be neutralized by a banana peel, imagine a superhero who was useless when it rains. Shyamalan reused the weakness for the aliens in Signs, which was even sillier. Why try to conquer a planet that is two-thirds covered in the stuff that can kill you? But I digress…). And Dunn’s arch-enemy is his polar opposite—like Batman, bastion of order, having to tangle with the anarchic Joker, or the physically powerful alien Superman having to constantly fight the intellectually gifted, albeit completely human, Lex Luthor, the indestructible Dunn must contend with a man with a rare bone disease that makes his bones incredibly fragile.

Unbreakable did well at the box office, but disappointing in comparison to The Sixth Sense. This can be chalked up to the ad campaign for the film, which tried to portray it as a psychological thriller in the mold of Shyamalan’s first film.

As it stands, Unbreakable is an example of the way that the world of comics have influenced filmmakers. Two years later, we would see a comic book creator become a filmmaker.

As it stands, Unbreakable is an example of the way that the world of comics have influenced filmmakers. Two years later, we would see a comic book creator become a filmmaker.

James Robinson, like Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman before him, was a British writer who made a big splash in America by reimagining a long-standing DC Comics character. Moore’s character, as we already mentioned, was Swamp Thing. Gaiman’s was the Sandman. Robinson made his name revamping Starman. Starman, like Sandman, was a character first created in the Golden Age of Comics (in 1941 to be exact) who was revamped and refigured into a number of different versions before finally hitting the right one. Robinson’s Starman was the son of the original, a reluctant hero who wrestled with family baggage as often as he did with the bad guys.

Calling Starman one of the best comic books to come out of the 1990s is the textbook definition of a backhanded compliment. The decade was known as a pit of bloated excess, marketing gimmicks and quantity over quality. However, Starman was one of the few comic books to come out of that era that truly deserved to be called great.

Calling Starman one of the best comic books to come out of the 1990s is the textbook definition of a backhanded compliment. The decade was known as a pit of bloated excess, marketing gimmicks and quantity over quality. However, Starman was one of the few comic books to come out of that era that truly deserved to be called great.

The comic book series ended in 2001 and Robinson moved on to Hollywood. In 2002, he wrote and directed Comic Book Villains, a film that spent about 15 seconds in theaters if that long. It wasn’t a superhero film at all, but comic books provided the MacGuffin that propelled the film’s crime noir plot along. The film centered on a collection of valuable comics dating all the way back to the Golden Age. The collector died and two rival comic book stores vie to get the expensive books by any means necessary. Unfortunately, the collector’s mom refuses to sell. As the owners of each store try to change the woman’s mind, their competition for the books soon turns nasty…and quite deadly.

Robinson’s script presented the story with dollops of black comedy and heaping helpings of the dark side of human nature. His cast might not have been A-list, but it was beyond great. Character actors such as Donal Logue, D.J. Qualls, Eileen Brennan and Cary Elwes fill in the leads and make their characters at once likeable and detestable. It’s well worth a look if you come across it on Netflix or if you have room on an Amazon gift card.

The final film we are going to talk about today takes the idea of applying realism to the superhero tropes to a new level, employing a popular style of filmmaking.

The final film we are going to talk about today takes the idea of applying realism to the superhero tropes to a new level, employing a popular style of filmmaking.

The “found footage” genre exploded in popularity in 1999 with the release of The Blair Witch Project, the film that became the trademark of the genre. That movie introduced the conceit that what you were seeing on screen was real, culled from footage filmed by the characters in the film, typically found after something awful happened to them. This conceit usually appears in horror films, where the pseudo-realism adds a creepy sense of dread to the scares. However, it was applied to the superhero genre with 2012’s Chronicle.

In this case, the found footage was taken by the three teens who gained telekinetic powers after coming in contact with a strange, radioactive rock. It chronicled their exploits in using their powers, which typically involved playing cruel tricks on unsuspecting townsfolk. It also documented the corrupting influence these newfound powers had on one of their members as he spiraled out of control into pure evil.

This was deconstructing the idea of superpowers for the YouTube generation. It tapped into the fact that if kids nowadays gained superpowers, they would not immediately go out and track down bank robbers. They’d get their laughs by scaring little girls in toy stores by making the stuffed animals appear to come to life. And they’d record it, not because their powers are amazing, but rather because they were recording their life any way and their origin just happened. Even without the “found footage” conceit, it would have been a realistic portrayal. The conceit just added another layer of realism.

Next up, we’ll look at some kid friendly films that examine the superhero, including one of the best superhero films of all time (and one of the worst).