In a multi-part series, Comic Book Film Editor William Gatevackes will be tracing the history of comic book movies from the earliest days of the film serials to today’s big blockbusters and beyond. Along with the history lesson, Bill will be covering some of the most prominent comic book films over the years and why they were so special. This time, we’ll talk about the first three of the best “superhero” films that only appeared in comics after the films were released.

Fair warning, you might have issue with these three film franchises being covered in the next three installments being called “superhero” movies. I’m here to make the case they are. But even if you don’t buy my argument, you have to admit the connection between these films and the world of comics is a tangible one.

These franchises have a lot in common. Each received life in comics after its first film opened, and the world of comics played a part in their creation to some extent. Each franchise was started by directors whose talent made them the biggest names in the film world. And each franchise was a case of diminishing returns after the big splash made by the first installment.

Some might ask, “Why is RoboCop on the list and the other famous Orion release of the ’80s, The Terminator, not? Couldn’t that film be considered an unofficial comic book film?” Yes, it could. But the ties between RoboCop and comics are a little bit stronger.

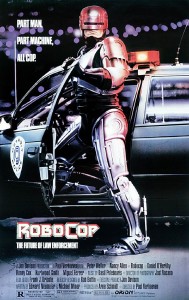

Director Paul Verhoeven has admitted in a 2002 interview with Dutch website XI Online that RoboCop, Verhoeven’s first major American film, was inspired by British comic book character, Judge Dredd, and you can see it, too. RoboCop takes place in a similar dystopian near-future as Dredd, is offered as the last word in law enforcement like Dredd, and often acts as judge, jury and executioner, too, like Dredd. But I don’t think the comic book inspirations end there.

In 1974, Marvel Comics came up with a character called Deathlok. He was a soldier named Luther Manning from a dystopian future version of Detroit, Michigan who is fatally injured in battle. Before he dies, his body is retrieved and what can be saved is rebuilt into a cyborg by an evil corporation with the intent of using the man-machine to work towards their interests. He eventually gains independence and fights against his programming. RoboCop is Alex Murphy, a police officer in a dystopian future version of Detroit, Michigan who is fatally injured in the line of duty. Before he dies, his body is retrieved and what can be saved is rebuilt into a cyborg by an evil corporation with the intent of using the man-machine to work towards their interests. He eventually gains independence and fights against his programming.

In 1974, Marvel Comics came up with a character called Deathlok. He was a soldier named Luther Manning from a dystopian future version of Detroit, Michigan who is fatally injured in battle. Before he dies, his body is retrieved and what can be saved is rebuilt into a cyborg by an evil corporation with the intent of using the man-machine to work towards their interests. He eventually gains independence and fights against his programming. RoboCop is Alex Murphy, a police officer in a dystopian future version of Detroit, Michigan who is fatally injured in the line of duty. Before he dies, his body is retrieved and what can be saved is rebuilt into a cyborg by an evil corporation with the intent of using the man-machine to work towards their interests. He eventually gains independence and fights against his programming.

Now, this could be a big coincidence, but if the powers that be were inspired by a comic with limited exposure in the U.S. at the time, they could have very well been familiar with the rather obscure Deathlok. Nothing has been said officially if Deathlok inspired RoboCop, so this is all speculation. But it is worth thinking about.

Regardless of the inspiration, RoboCop was an awesome film, well ahead of its time. On one level, it works as a great futuristic sci-fi action film. On another level, it is a cutting piece of satire of the era that still rings true today. Some of the jabs are obvious—television, commercials and the need for consumer products, others are more subtle—the jingoism of Regan’s America, the corporatization of public services, and violence in film (satire which was lost on the MPAA, who made director Verhoeven tone down the violence in order to avoid an X Rating, and many audience members).

The film was well received critically and financially, which means sequels. But director Verhoeven and writers Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner would not be returning for RoboCop 2.

But this did not seem like much of a problem. To replace Verhoeven, the powers that be chose Irvin Kershner. It might be a stylistic step down, but Kershner did direct The Empire Strikes Back, the much lauded second installment in the Star Wars franchise. For writing, they turned to the world of comics. They looked towards a name that was getting a lot of attention for a series that covered a lot of the same themes as RoboCop. The book was The Dark Knight Returns and the writer was Frank Miller.

But this did not seem like much of a problem. To replace Verhoeven, the powers that be chose Irvin Kershner. It might be a stylistic step down, but Kershner did direct The Empire Strikes Back, the much lauded second installment in the Star Wars franchise. For writing, they turned to the world of comics. They looked towards a name that was getting a lot of attention for a series that covered a lot of the same themes as RoboCop. The book was The Dark Knight Returns and the writer was Frank Miller.

On paper, this seemed like a project that while not being as good as the original, it would be good in its own right. However, on film, 1990’s RoboCop 2 was a resounding disappointment.

Judging by how bad his writing would eventually become, it would be easy to blame Frank Miller for how bad these sequels turned out. However, Miller has stated that the producers rewrote his script to an absurd level and what was on the screen only had traces of what he originally wrote. His original script was adapted into comic book form in 2003 by Avatar Press. It proved that he was right. Oh, Miller’s version was bad, just bad in a different way, but practically the only thing that remained the same in both versions was the introduction of a new cyborg officer (named…RoboCop 2! Hilarity!) and an even more war-torn Detroit.

Where Miller’s version and the version that made it to the screen went wrong was that both failed to grasp what made the original so great. Instead of uberviolence that pointed out the absurdity of movie violence, it was the type of gratuitous violence the first film mocked. Instead of biting satire, it was ham-fisted mockery of easy pop culture targets. Instead of shocking us with the depravity that humans can stoop to, it gives us a twelve-year-old drug lord and expects us to be shocked.

Miller did get something out of it. He was able to visit the set everyday to learn the art of filmmaking. He also garnered the first of what would be a string of cameos in feature films.

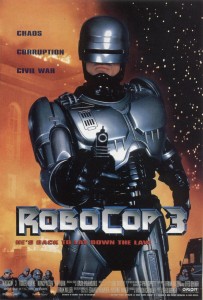

While the film was a critical failure, it made enough money to garner another sequel. Miller was brought back to write RoboCop 3, and he accepted the job thinking this time would be different and he would finally be able to reintroduce plot points that were removed from his script for RoboCop 2. He was wrong. While some elements Miller wanted made their way in—the forcible relocation of Old Detroit residents, the use of mercenaries to supplement the Detroit police force—his script was changed even more this time around, due to the way the character morphed through in his appearances in other media.

While the film was a critical failure, it made enough money to garner another sequel. Miller was brought back to write RoboCop 3, and he accepted the job thinking this time would be different and he would finally be able to reintroduce plot points that were removed from his script for RoboCop 2. He was wrong. While some elements Miller wanted made their way in—the forcible relocation of Old Detroit residents, the use of mercenaries to supplement the Detroit police force—his script was changed even more this time around, due to the way the character morphed through in his appearances in other media.

After the success of the first RoboCop, the franchise branched out into other medium. It became a Marvel comic book which presented a more kid friendly version of the character and ran from 1990-1993. Marvel, through its Marvel Productions arm, also produced a syndicated cartoon in 1988 which, while darker than the other cartoon fare of the time, was considerably less violent and gory than the film. The property also made its way into the world of video games, again with much of its content toned down.

The result was that the RoboCop brand became, well, more kid friendly. The producers of the film franchise recognized this and decided to make RoboCop 3 a more kid-accessible PG-13.

Peter Weller, who was excellent in the role of RoboCop, is gone for this installment, replaced by Robert John Burke. Nancy Allen stayed for a few scenes before getting herself killed off. The violence was toned down and kid-friendly plot elements such as a jet pack for RoboCop and robo-ninjas as his enemies put the final nail in removing all traces of what made the first film great.

Peter Weller, who was excellent in the role of RoboCop, is gone for this installment, replaced by Robert John Burke. Nancy Allen stayed for a few scenes before getting herself killed off. The violence was toned down and kid-friendly plot elements such as a jet pack for RoboCop and robo-ninjas as his enemies put the final nail in removing all traces of what made the first film great.

There has been a remake in the works since 2005. Director Darren Aronofsky was briefly attached to the project before Jose Padilha was chosen to take over the reins. This should be coming out later in the year that this post will run, so I’ll just have to add to it as time goes by.

Next up, Sam Raimi examines the superhero archetype years before he directed Spider-Man.