In a multi-part series, Comic Book Film Editor William Gatevackes will be tracing the history of comic book movies from the earliest days of the film serials to today’s big blockbusters and beyond. Along with the history lesson, Bill will be covering some of the most prominent comic book films over the years and why they were so special. This time, we’ll talk about a different kind of British invasion as some British comic book icons come over to the States in film form.

If there is a reoccurring theme of this history, it’s that Hollywood often screws up the American comics they adapt. Whether it be hubris, a lack of understanding, or plain old incompetence, more comic book movies are changed for the worse by Hollywood because the powers that be just “didn’t get it.”

If Hollywood has a hard time making movies out of comics published in its own country, how would it fare adapting Britain’s favorite comic book characters? Judging by two examples from the 1990s, it would not fare well at all.

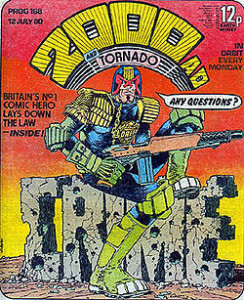

Judge Dredd is perhaps the most famous British comic book character of all time. I believe that only Miracle/Marvelman would give him a run for his money. Created by Pat Mills, John Wagner and Carlos Ezquerra and first appearing in the second issue of the seminal British comic book magazine 2000 A.D., Dredd was a combined cop, judge, and executioner in a post-apocalyptic United States. He is the best cop in Mega-City One, the future version of New York City, if New York City took up most of the Eastern Seaboard. His jurisdiction ran from busting petty vandals to stopping another nuclear Armageddon. He would face off against mutants, cyborgs and gangs in the process of doing his job.

Judge Dredd is perhaps the most famous British comic book character of all time. I believe that only Miracle/Marvelman would give him a run for his money. Created by Pat Mills, John Wagner and Carlos Ezquerra and first appearing in the second issue of the seminal British comic book magazine 2000 A.D., Dredd was a combined cop, judge, and executioner in a post-apocalyptic United States. He is the best cop in Mega-City One, the future version of New York City, if New York City took up most of the Eastern Seaboard. His jurisdiction ran from busting petty vandals to stopping another nuclear Armageddon. He would face off against mutants, cyborgs and gangs in the process of doing his job.

The character appeared in every issue of 2000 A.D. since his first appearance in 1977 and was one of the few British comic book characters to get his own magazine. British creators that went on to have some success in the States worked on the character, including Brian Bolland, Ian Gibson, Brendan McCarthy, Alan Grant, Steve Dillon, Barry Kitson, John Higgins, Garry Leach, Kevin O’Neill, Liam Sharp, Glenn Fabry, Alan Davis, Garth Ennis, Mark Millar, Grant Morrison and many, many more.

Judge Dredd has quite a following in the United States, with many fans becoming exposed to the character through reprints, through DC licensing the characters, or imports of British mags. This stateside popularity caught the attention of Hollywood producers, who decided, in 1995, to give the character his own movie called Judge Dredd.

The fate of the film was sealed when Sylvester Stallone was cast in the lead (although, to be fair, it might not have been a better movie if the producers’ original choice, Arnold Schwarzenegger, agreed to take on the film). Cobra proved he wasn’t good at being a grim dispenser of justice. And Dredd wasn’t the type of role where he could use his charm and charisma to get by.

The fate of the film was sealed when Sylvester Stallone was cast in the lead (although, to be fair, it might not have been a better movie if the producers’ original choice, Arnold Schwarzenegger, agreed to take on the film). Cobra proved he wasn’t good at being a grim dispenser of justice. And Dredd wasn’t the type of role where he could use his charm and charisma to get by.

So it started off bad, but the filmmakers made it worse. Instead of the subversive satire and humor, we get a wacky comedy sidekick, and, adding insult to injury, they cast Rob Schneider in the role. They add a possible romance with Diane Lane’s character, Judge Hershey, when the comic’s Dredd’s foregoing any romance in favor of pursuing justice is a pretty big character trait. And, in what might seem like a minor point to the uninitiated but is a big deal to the Dredd fans, Stallone goes through most of the movie sans Dredd’s trademark helmet. In the characters 35 year plus career in the comics, the adult Dredd only took off his helmet a handful of times, and never in any way that you can make out his features.

Judge Dredd got a remake this year with Dredd, and it was better even before the first frame was shot. John Wagner, co-creator, gave the script an a-ok while the film was in pre-production, saying it was closer in tone to the original comics than the Stallone vehicle. That’s a pretty good way to start a reboot to a franchise that wasn’t done right the first time around, isn’t it?

As for the movie itself? Well, it was a vast improvement over the Stallone version (but it was hard for it not to be). As a comic book adaptation, Dredd remained true to feel of the source material, capturing the characterization of Judge Dredd to a T and employing the graphic violence and morbid humor quite well. As a film, Pete Travis’ stylized direction is visually interesting, and the film holds up well against other films set in a grim future such as RoboCop, Road Warrior, and Escape From New York.

As for the movie itself? Well, it was a vast improvement over the Stallone version (but it was hard for it not to be). As a comic book adaptation, Dredd remained true to feel of the source material, capturing the characterization of Judge Dredd to a T and employing the graphic violence and morbid humor quite well. As a film, Pete Travis’ stylized direction is visually interesting, and the film holds up well against other films set in a grim future such as RoboCop, Road Warrior, and Escape From New York.

Unfortunately, the ghost of the Stallone version kept people out of the theaters. As of October 25, 2012, after what was then five weeks of release, the film earned less than half of its $50 million budget back ($23,467,110 to be exact) worldwide, with little chance of it making up the difference. This is a shame because I truly believe the film deserved a bigger audience than it got. Hopefully, its audience will find it on home video.

The same year the first Judge Dredd film came out, Hollywood adapted another satirical British comic book character from a post-apocalyptic Earth. The film is Tank Girl, based on the character of the same name created by Alan Martin and Jamie Hewlett (who would later gain fame with his partnership with Damon Albarn in creating the multimedia rock group, The Gorillaz).

Whereas Judge Dredd was a violent and grim satire using a dystopian future as a commentary on the present-day world, Tank Girl takes a more absurdist take on the theme. Tank Girl, an Australian mercenary who owns and lives in a tank, made her first appearance in Deadline #1 in 1988. Her boyfriend is a mutated anthropomorphic kangaroo. Her missions include such tasks as procuring colostomy bags for the Australian president. She became an underground sensation and a counterculture icon, which means she was a perfect choice for Hollywood to try to make into a mainstream film. Of course, this being Hollywood, they had no idea how to get this done.

Whereas Judge Dredd was a violent and grim satire using a dystopian future as a commentary on the present-day world, Tank Girl takes a more absurdist take on the theme. Tank Girl, an Australian mercenary who owns and lives in a tank, made her first appearance in Deadline #1 in 1988. Her boyfriend is a mutated anthropomorphic kangaroo. Her missions include such tasks as procuring colostomy bags for the Australian president. She became an underground sensation and a counterculture icon, which means she was a perfect choice for Hollywood to try to make into a mainstream film. Of course, this being Hollywood, they had no idea how to get this done.

The film was directed by self-professed Tank Girl fan Rachel Talalay and was produced by Deadline’s publisher Tom Astor, so you’d think that the film would be a fairly faithful adaptation, right? Not when it’s being done by a major Hollywood studio it’s not. United Artists put the film through a gauntlet of test screenings and focus groups and more focus groups, and calling for script changes and editing cuts accordingly. Talalay had this to say about the experience as it pertains to one particular scene:

“Then there was a tag where it rained and TG/Jet G/and Sub Girl plan to take over the world (the umbrella hat shot) (rather than the animation). Someone in the obnoxious focus group said they didn’t understand why it rained. So out it went. We put in the animation, which I liked anyway, but first time we screened it with the animation, someone in the focus group said I wish it had rained at the end. Then everyone agreed. I hate test screenings, especially when the studio takes one person’s opinion to be gospel.”

By trying to make it a film that would please everyone, it made the film a disappointment to Tank Girl’s fans, creators and the general public. It grossed under $6.6 million worldwide against a $25 million dollar budget.

Next time, Will Smith gets jiggy with it in a stealth comic book adaptation.