On Friday, Laura Siegel Larson, daughter of Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel issued a letter to Superman fans to give them her feeling on her family’s 15 year struggle to wrestle their half of the rights to Superman from Warner Brothers/DC Comics. Here is that letter:

Some might read this and feel sympathetic to Siegel Larson and her plight, and perhaps just a bit angry at Warner Brothers at their callous treatment of the Siegel family over the years. Others might read the letter and also get angry–at Siegel Larson, for playing to people’s emotions and twisting facts so her side of the matter appears in a more positive light. Others might read her defense of Marc Toberoff and wince, feeling sad that she would defend someone who might not exactly be working in her best interests.

Or, if you are like me, you have a mixture of all the above feelings after reading that letter. See, for as much as each side wishes to present the issue as a case of black and white, it’s not. The lawsuit to the rights for Superman, a struggle that will get more and more press as we come closer to The Man of Steel’s June 14, 2013 release date, is a sickening blend of grays. And the reason why there is so much debate and discussion over the issue is because there are valid talking points for each side. The purpose of this post is to present these talking points to you and explain why there are no easy answers in this conflict.

$130

The world of comic book collecting is ruled by the law of buy low and sell high. You buy a comic book for $3.99, and you hope that there is something about it–a variant cover, a new character being introduced, a popular storyline taking place–that causes people to want it. If it works out, you can triple your investment overnight, and, in rare cases, you can have a book worth hundreds of dollars in a matter of years.

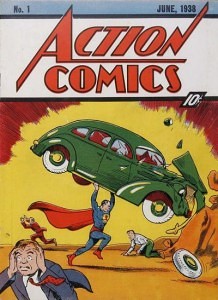

This adds a bitter sense of irony to the Superman situation. Because, you see, DC Comics bought the rights to Superman from Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in 1938 for $130. To put that into perspective, if you factor in inflation, that would be around $2,048 dollars in today’s money. One of the most iconic, most recognizable characters in pop culture across the entire world, and he was bought for less that what you’d pay for a top of the line high-definition television set today.

Why such a low price? Well, we must consider that the sale took place at the tail-end of the Great Depression. It was hard for two 23-year-old young men to haggle over money when unemployment was at 19% throughout the country.

And comic books at the time were a bit of a seedy enterprise. The medium got its start as publishers simply folded popular Sunday newspaper comics sections into a book form and sold it at newsstands. When the comic book format grew in popularity, publishers supplemented the reprint material with original material similar to the most popular comic strips of the day–hard-boiled detective stories in the mold of Dick Tracy, gag strips that resembled Mutt and Jeff, space epics akin to Flash Gordon or Buck Rogers and so on. Experience and quality of work weren’t important to the publishers, only speed and productivity. To keep costs low, they hired kids who would work cheap and be able to keep up with demand. Many comic legends such as Jack Kirby, Joe Kubert and Will Eisner started working in comics when they were in their teens. Others such as Bob Kane, Joe Simon and, yes Siegel and Shuster, were in their early twenties. Even though the publishers most likely weren’t paying these kids what they deserve, whatever they brought in help put food on their family’s table.

And, hard though it may be to believe today, at the time, Superman was a risky concept. It was quite unlike anything else on the market in the 1930s. Siegel and Shuster intended the concept to be sold to the more respectable newspaper comic strip syndicate but were turned down by at least two syndicates. DC Comics was at best a “safety school” for Superman. This could be another reason why the pair didn’t squabble over the price–they didn’t know if there would ever be any other takers.

And, hard though it may be to believe today, at the time, Superman was a risky concept. It was quite unlike anything else on the market in the 1930s. Siegel and Shuster intended the concept to be sold to the more respectable newspaper comic strip syndicate but were turned down by at least two syndicates. DC Comics was at best a “safety school” for Superman. This could be another reason why the pair didn’t squabble over the price–they didn’t know if there would ever be any other takers.

Superman went on to revolutionize comic books, making the superhero popular, and becoming an indelible piece of our modern-day cultural landscape. But from the very beginning, you can say the poor treatment of Siegel and Shuster began. However, the company did not always treat the pair quite as bad.

Paupers to Princes to Paupers

Much is made of how much Siegel and Shuster were paid for the rights to Superman, and the many articles note that the pair were destitute during the later periods of their life, but what I find interesting is how much they paid while doing Superman. In 1940, the Saturday Evening Post reported that the pair were making $75,000 per year from Superman comics and merchandise, which would be the equivalent of just about $1.2 million dollars today. According to Larry Tye’s book, Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero, Siegel claims the duo were making half that. Even still, that would be close to $38,000 a year for both, $19,000 for each. It was probably a pittance compared to what DC was making off their works, but it was ten times the average yearly salary in 1940 of $1,900 .

Much is made of how much Siegel and Shuster were paid for the rights to Superman, and the many articles note that the pair were destitute during the later periods of their life, but what I find interesting is how much they paid while doing Superman. In 1940, the Saturday Evening Post reported that the pair were making $75,000 per year from Superman comics and merchandise, which would be the equivalent of just about $1.2 million dollars today. According to Larry Tye’s book, Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero, Siegel claims the duo were making half that. Even still, that would be close to $38,000 a year for both, $19,000 for each. It was probably a pittance compared to what DC was making off their works, but it was ten times the average yearly salary in 1940 of $1,900 .

The duo bought fancy houses with modern luxuries such as paneled bars and air conditioning. They would buy fancy cars, mink coats and jewelry. Technically, they weren’t living above their means, but they weren’t truly prepared for their means to change. When the Saturday Evening Post article hit, Shuster’s eyesight was bad and getting worse–half of his cut of the contract was going to ghost artists who would trace over his loose outlines for the art. Unfortunately, actions taken by the pair would jeopardize their employment as well.

Lawsuits

From the start, Siegel and Shuster were trying to sell DC Comics on the idea of stories based on Superman as a child. However, every proposal they offered was shot down. Imagine Jerry Siegel’s surprise when, after returning from service during World War II, that DC had started a Superboy feature based on his ideas with no input or involvement from either himself or Shuster.

From the start, Siegel and Shuster were trying to sell DC Comics on the idea of stories based on Superman as a child. However, every proposal they offered was shot down. Imagine Jerry Siegel’s surprise when, after returning from service during World War II, that DC had started a Superboy feature based on his ideas with no input or involvement from either himself or Shuster.

Naturally, Siegel and Shuster were incensed. They sued DC Comics in 1947 not only for using their ideas for Superboy without their permission, but also to terminate their contracts with the company and get back the rights to Superman as well.

The courts were only partially in their favor. The courts disavowed their claims for Superman, but agreed that the had a right for compensation for Superboy. DC Comics settled with the pair for $94,000 in exchange for the agreement that Shuster and Siegel would give up all rights to Superman, Superboy and any auxiliary characters they created for the company. After legal fees, the pair took home about a third of that.

Siegel believed that after the lawsuit, he and Shuster were blacklisted in the industry. Shuster’s eyesight would make him leave the industry within ten years time. Siegel would work sporadically in comics for years afterwards, typically under pen names. The team would reunite only once after their tenure at DC was over, creating a forgettable character called Funnyman for Magazine Enterprises in 1948.

By 1975, Siegel and Shuster were in bad shape. They had once again sued DC for the right to the Superman copyright in 1967 and by 1973, they had lost their appeal. Their lawyers advise them not to go to the Supreme Court because the would not be able to afford the expense and that DC was likely to settle the case. Both were practically destitute (Siegel was complaining of money troubles as early as 1953). When no settlement came, the pair used the recent news that Warner Brothers bought the rights to Superman with the intention make a feature film to start a publicity campaign of their own.

Aided by Neal Adams, at the time DC’s hottest artist, and Jerry Robinson, who worked for DC by proxy in the employ of Batman creator Bob Kane, creating Robin and the Joker for Kane and who was a successful commercial artist and editorial cartoonist, the creators launched a media blitz, playing off the fact that Superman earned DC Comics millions yet his creators were living in poverty. The New York Times wrote a story on the situation that was picked up by papers across the country. Siegel and Shuster appeared on many popular news programs of the day. It became a public relations fiasco for DC Comics.

Throwing themselves on the sympathy of the American public worked for the creators, as DC Comics would settle with Siegel and Shuster once more. The company would give them a yearly pension of $20,000 a year for the rest of their lives, adjusted accordingly in regards to inflation (by 1988, the yearly total was up to $80,000). Their caretakers (wife Joanne for Jerry, brother Frank for Joe) would get the pension if they died before them at a rate of $20,000 a year until 1985, then $10,000 a year until their death. The team would get health care coverage and would be credited as the creators of Superman in whatever medium he would appear from then on. But Siegel and Shuster were once again asked to state that they had no rights to the Superman family of characters.

It seem that the issue would be settled. And for all intents and purposes it was–for over twenty years. However, a new law passed just a year later would open the discussion again in the future.

The Copyright Act of 1976

The Copyright Act of 1976 was intended to protect corporate interests. The act was designed to extend the life of copyrights and delay copyrighted works from entering into the public domain. Before 1976, a corporation could hold a copyright for only 56 years (two, 28 year terms). The 1976 act extended the copyright protection for works created after 1978 to 50 years after the death of the author in case where the author owned the copyright, 95 years for anonymous works or works for hire. It extended the total copyright protection on works before 1978 from 56 years to 75 years.

However, that extension act allowed creators or their direct heirs who transferred the copyrights over to a corporation the opportunity to terminate, within a five year window, that transfer after 56 years. The copyright for Superman turned 56 in 1994, which meant the Siegels had until 1999 to terminate the copyright. Joanne and Laura Siegel filed the termination in 1997 (Jerry Siegel passed away the year before). They would file a similar termination notice for Superboy in 2004.

The Shuster family missed out on this filing. However, the Copyright Extension Act of 1998 (also known as the Mickey Mouse Protection Act (due to Disney’s lobbying for a change to copyright law) or the Sonny Bono Act (after the ex-pop star, then Senator who proposed the act)) extended the length of copyrights once again, but also extended the time creators can terminate their copyrights to 75 years and allowed executors the power to do so. This gave Mark Peary, Joe Shuster’s nephew and executor of his estate (Shuster passed away in 1992), another chance to file his termination paper work, which he did in January of 2004, with an effective termination date in 2013. If DC Comics did nothing, the Siegel and Shuster families would own 100% of the the Superman copyright by 2013. But, of course, DC Comics did not intend to go down without a fight.

The Shuster family missed out on this filing. However, the Copyright Extension Act of 1998 (also known as the Mickey Mouse Protection Act (due to Disney’s lobbying for a change to copyright law) or the Sonny Bono Act (after the ex-pop star, then Senator who proposed the act)) extended the length of copyrights once again, but also extended the time creators can terminate their copyrights to 75 years and allowed executors the power to do so. This gave Mark Peary, Joe Shuster’s nephew and executor of his estate (Shuster passed away in 1992), another chance to file his termination paper work, which he did in January of 2004, with an effective termination date in 2013. If DC Comics did nothing, the Siegel and Shuster families would own 100% of the the Superman copyright by 2013. But, of course, DC Comics did not intend to go down without a fight.

The “Peanuts” Settlement

Even though DC Comics/Time Warner were publicly stating that Siegel and Shuster’s work on Superman was work for hire (a dubious claim because DC itself had made the fact that the pair brought Superman to DC part of the legend of the character’s creation), the corporation began settlement talks with the Siegel family.

According to documents found by Danny Best, as of 2001, a potential settlement was drawn up by DC, one which the Siegel’s lawyers at the time recommended they take, one Laura Siegel Larson referred to as “peanuts.”

What were the terms of this settlement? $3,000,000 immediately, at least $500,000 per year, 6% of all media and merchandise exclusively featuring Superman or the Spectre (another Siegel creation owned by DC), 3% of any media or merchandise where Superman and Spectre shared a starring role with another DC character, and 1.5% of any media or merchandise where the Spectre and Superman were part of an ensemble cast. And DC would continue to honor the terms of the 1976 agreement, which were by this point up to $135,000 a year. DC did require the Siegels to transfer the full rights to Superman to DC in response to this agreement.

Once again, this would seem like peanuts in comparison to the billions DC rakes in with the Superman property. But I’d think even people who were highly allergic to peanuts would be willing to jump at the opportunity to be millionaires overnight.

But not the Siegels. They rejected the settlement that was all but approved and less than two years later they had new representation–Marc Toberoff.

DC tried a similar settlement with the Shuster family in 2005. The settlement had nothing to do with the Spectre, as Shuster did not have a hand in creating the character, and the per year payment would be $1 million, but the Shuster family would also get royalties like the Siegels. The Shusters also refused the settlement and, perhaps not quite a coincidence, signed on with Marc Toberoff as a representative.

Marc Toberoff: A Sheep in Wolf’s Clothing, or a Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing?

…or a wolf pretending to be a sheep in wolf’s clothing?

…or a wolf pretending to be a sheep in wolf’s clothing?

Prior to his involvement with the Siegels and the Shusters, Marc Toberoff was viewed as a staunch defender of artist rights. He was the lawyer who would represent Davids like the Siegels and Shusters against Goliaths such as the Time Warner/DC Comics conglomerate–and win. He won important decisions in the original creators behind the Dukes of Hazzard and Lassie franchises.

It was under his watch that the Siegel and Shuster families won an important victory in a court of law. He got a judgement that states that since Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster reworked a series of trial comic strips into the story that became the Superman stories in Action Comics #1 and #2, they own the copyright to whatever part of the Superman mythos that appeared in those two issues. This includes, but is not limited to, Superman’s origin, his secret identity of Clark Kent, Lois Lane being a love interest, and elements of the Superman costume that made its debut in those issues. Everything that came after, the ruling states, was done as work for hire for DC comics.

It appeared that the Siegels and Shusters were well on their way to becoming part owners of the characters Jerry and Joe created, and that DC would be losing a large chunk of their most iconic characters. However, there was a startling twist in the offing.

One morning, top executives at Warner Brothers and DC came into work and were greeted by a package. The package contained a number of documents stolen from Toberoff in 2006 by an anonymous culprit. The documents were covered by a letter that contained a timeline telling an interesting story about what supposedly were Toberoff’s true intentions.

The timeline and supporting documents, which can be found here, paint Toberoff not as a valiant defender of an artist’s rights, but a sneaky manipulator who was out to make the most money at the expense of the Siegel and Shuster families. The timeline indicates that Toberoff wooed the families with false promises of a billionaire willing to support families’ in making a Superman film that would go into competition with any Warners’ Superman film, but ended up negotiating a himself a 47% cut of the Superman copyright as part of the “contingency” agreement Siegel Larson spoke of in her letter. The timeline also indicates that Toberoff has no intention of letting the families assume total ownership of Superman. It states that Toberoff is simply holding off negotiations for as long as possible so the settlement, and his enormous cut of it, will be even larger.

DC Comics immediately tried to gain the documents in the illegal package through legal means only to be refused by Toberoff on attorney/client privilege. Unfortunately for Toberoff, he tried to work with Federal authorities to investigate the theft. In the process, he releases some of the documents in question to the Feds to aid in their investigation, thinking that he could waive the attorney/client privilege for only that one time and only to that specific party. DC and, more importantly, the courts disagreed. They stated that once the documents were released to the feds, they should be released to everyone. DC then was able to get their hands on the timeline legally, and used it as the basis of a suit to get Toberoff removed case and/or the Siegel suit dismissed entirely due to his putting his own interest above his clients.

The Court of Public Opinion

Laura Siegel Larson’s letter calls to mind a letter her mother Joanne meant to send to Warner Brother executives before her death that somehow was “leaked” to news organizations after her passing. There are a number of parallels–painting Warners/DC as bullies picking on sick women (with a list of medical maladies included in the text), a chastising of DC’s for going after Toberoff, and, most importantly, words about how DC looks to the general public.

In my opinion, both letters are attempts to garner sympathy and support among the general public, much akin to the public support in 1975 that helped Siegel and Shuster get their pensions and health benefits. But there is one main difference, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created Superman through their own talent, creativity and imagination. While they were living in poverty, dealing with deteriorating health, their greatest creation was earning millions for their former employers. They were victims of the great machine, two men who deserved better and a sympathetic public viewed them as such.

Meanwhile, in the comic book community, there are a lot of people who view the Siegel heirs lawsuit negatively. Whether it be the irrational “They’re trying to steal my Superman from me” internet trolls or the people who have serious issues with people who had little or nothing to do with creating the character reaping any sort of benefits, regardless if they were legally entitled to them or not (Joanne Siegel was the model for Lois Lane, but didn’t marry Jerry until 1948, a year after the writer stopped working on Superman full time. She was the only person in the lawsuit who could claim on having any influence on the final product). While there are many who support Laura Siegel Larson’s claims, there will never be a consensus of anger among fans over the issue like the one that cause the PR nightmare for DC in the 1970s.

And as for the mainstream media picking up the issue as a cause celebre like they did in the 70s, well, in today’s 24-hour news cycle it’s hard for a story like Laura Siegel Larson’s to gain any traction. It simply isn’t sensational enough. Heck, it wasn’t even pressing news among the comic book blogosphere. The letter was released on Friday while a massively popular comic book convention, New York Comic Con, was going on. The Beat and Robot 6 wrote a blurb on it on Saturday, Siegel Larson had to e-mail Bleeding Cool on Monday to get coverage, and, as of last night, Blog@Newsarama hasn’t covered it at all.

Personally, I think the Siegel and Shuster families should be sharing in the Superman wealth not only because they are legally entitled to but because Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster should have been sharing in the wealth when they were alive and it should have been a simple matter of the families inheriting their fortune. But the allegations about Toberoff concern me deeply. And the fact that Siegel Larson spends more time playing the victim card (while also playing the “David in the face of Goliath” card) than addressing the valid issues with her lawyer doesn’t sit well with me. It’s hard to feel sympathy for someone who is angry at a corporation that is cheating her out of money she deserves when she is defending a man who also is allegedly cheating her out of money she deserves.

There is a clock ticking on this issue, as the 2013 deadline is quickly approaching. Hopefully, there will be some kind of agreement, some kind of legal decision, that will benefit all parties. But judging on Laura Siegel Larson’s letter, we could be in for even more contentious legal wrangling for years to come.

The Laura Siegel Larson Letter: Only Part Of The Story http://t.co/V556yYO0