In a multi-part series, Comic Book Film Editor William Gatevackes will be tracing the history of comic book movies from the earliest days of the film serials to today’s big blockbusters and beyond. Along with the history lesson, Bill will be covering some of the most prominent comic book films over the years and why they were so special. This time, we’ll look at the comic that was created using tax refunds and became a multi-million dollar international phenomenon—Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

The story of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles is the story of America. It is the story of Thomas Edison and Henry Ford. It is the story of Steve Jobs and Bill Gates. It is the story that reality shows like American Idol and The Voice try to manufacture each and every season. It is the story of an underdog meeting up with fate and opportunity and taking advantage of both to find unimaginable success. It is the story of the American Dream.

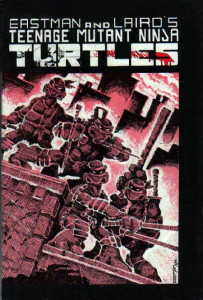

It all starts in Dover, New Hampshire, early 1980s. Kevin Eastman, a comic book fan, draws a picture of a turtle wearing a mask to make his friend and fellow comic book fan, Peter Laird, laugh. The gag photo started a conversation and then an exchange of ideas. Before long, they were pooling their income tax refunds, borrowing some money from Eastman’s uncle, and printing up 3,000 copies of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #1 as Mirage Studios (the mirage being that they were the only two at their “studios”).

It all starts in Dover, New Hampshire, early 1980s. Kevin Eastman, a comic book fan, draws a picture of a turtle wearing a mask to make his friend and fellow comic book fan, Peter Laird, laugh. The gag photo started a conversation and then an exchange of ideas. Before long, they were pooling their income tax refunds, borrowing some money from Eastman’s uncle, and printing up 3,000 copies of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #1 as Mirage Studios (the mirage being that they were the only two at their “studios”).

The influences that Eastman and Laid drew on were there from the first issue. The cover design is reminiscent of the design of Frank Miller’s Ronin miniseries. The origin and history of the Turtles ties into the Daredevil mythos, primarily Frank Miller’s addition to it (the Turtles are mutated by the same canister of radioactive waste that blinds Matt Murdock and gives him radar sense, their trainer is Splinter instead of Daredevil’s trainer, Stick, and the faceoff against the Foot clan of ninjas, a reference to DD’s ninja enemies, the Hand). The age of the heroes is a play on the popular “teen heroes” trend of the era, as exemplified by The New Teen Titans and The New Mutants. And, surely, the idea of doing an anthropomorphic, creator-owned, parody of various comic book genres and tropes was inspired by Dave Sim’s Cerebus. Even the names of the Turtles—Leonardo, Michelangelo, Donatello, and Raphael—were a jab at the artistic movement in comics of the day.

The influences that Eastman and Laid drew on were there from the first issue. The cover design is reminiscent of the design of Frank Miller’s Ronin miniseries. The origin and history of the Turtles ties into the Daredevil mythos, primarily Frank Miller’s addition to it (the Turtles are mutated by the same canister of radioactive waste that blinds Matt Murdock and gives him radar sense, their trainer is Splinter instead of Daredevil’s trainer, Stick, and the faceoff against the Foot clan of ninjas, a reference to DD’s ninja enemies, the Hand). The age of the heroes is a play on the popular “teen heroes” trend of the era, as exemplified by The New Teen Titans and The New Mutants. And, surely, the idea of doing an anthropomorphic, creator-owned, parody of various comic book genres and tropes was inspired by Dave Sim’s Cerebus. Even the names of the Turtles—Leonardo, Michelangelo, Donatello, and Raphael—were a jab at the artistic movement in comics of the day.

Even with a miniscule 3,000 copy print run (even the lowest selling comics had print runs in the tens of thousands), Laird and Eastman believed that they’d have copies left over. Two things worked in their favor—one, Laird, from his experience working at a newspaper knew of a thing called a press kit. He created one for TMNT and sent it out to major media outlets and, two, the comic industry was on the verge of a black and white comic boom, so interest in black and white indies, which TMNT was, was at an all time high.

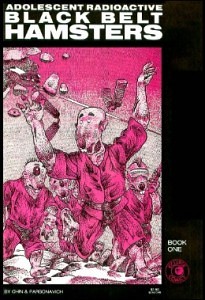

The first printing sold out (and it got to the point that counterfeit copies were made). Then the second printing sold out. Then a third printing sold out as well. Eastman and Laird decided to continue the series. The second issue more than tripled its print run. The pair had a success on their hands. They were able to not only pay back their debt but also actually make a living. Their parody began to be parodied—Eclipse Comics’ Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters, Blackthorne Publishing’s Pre- Teen Dirty-Gene Kung Fu Kangaroos and Cold-Blooded Chameleon Commandos, even Marvel got in the act with a proposal called Adult Thermonuclear Samurai Elephants, which was eventually reworked into a book called Power Pachyderms.

The first printing sold out (and it got to the point that counterfeit copies were made). Then the second printing sold out. Then a third printing sold out as well. Eastman and Laird decided to continue the series. The second issue more than tripled its print run. The pair had a success on their hands. They were able to not only pay back their debt but also actually make a living. Their parody began to be parodied—Eclipse Comics’ Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters, Blackthorne Publishing’s Pre- Teen Dirty-Gene Kung Fu Kangaroos and Cold-Blooded Chameleon Commandos, even Marvel got in the act with a proposal called Adult Thermonuclear Samurai Elephants, which was eventually reworked into a book called Power Pachyderms.

Licensors then started calling. First came a long-running animated TV show. Next came a very successful line of action figures. And then came the movies.

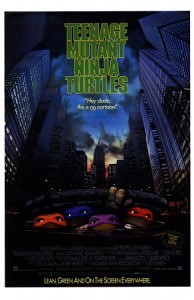

The first film, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles arrived in 1990.

The Turtle masks were made by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop (One of the last works Henson supervised before he passed away. The sequel to this film is dedicated to him.) and were a step above what was seen four years earlier with Howard the Duck. The tone of the film was somewhere between the darker tone of the first Eastman and Laird comic and the kid-friendly cartoons that were airing on TV concurrently. In the film, New York City is in the midst of a crime wave created by Shredder and his Foot clan of ninjas. The only group strong enough to fight him is a group of mutated terrapins—the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

The Turtle masks were made by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop (One of the last works Henson supervised before he passed away. The sequel to this film is dedicated to him.) and were a step above what was seen four years earlier with Howard the Duck. The tone of the film was somewhere between the darker tone of the first Eastman and Laird comic and the kid-friendly cartoons that were airing on TV concurrently. In the film, New York City is in the midst of a crime wave created by Shredder and his Foot clan of ninjas. The only group strong enough to fight him is a group of mutated terrapins—the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

Robbie Rist (Cousin Oliver from The Brady Bunch) and Corey Feldman would voice two of the Turtles (Michelangelo and Donatello respectively). Their rat mentor, Splinter, was voiced by Kevin Clash, the puppeteer that helped make Elmo the star of Sesame Street. Sam Rockwell had a small role as a thug in the film, one of his first film roles.

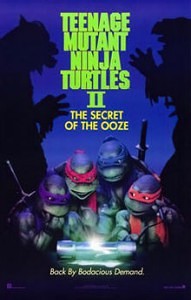

The film was a smash success, making over $200 million against a $13.5 million dollar budget. This pretty much guaranteed a sequel, which was 1991’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze.

The sequel came out at the height of the Turtles popularity, and suffered for it. The violence was toned down and the Turtles’ distinctive weapons were minimized. There was an eye towards merchandising as well, including an awkward cameo by the then-briefly popular Vanilla Ice, who sang “Ninja Rap” (“Go Ninja, Go Ninja, GO!”) during a fight scene at a club. The song was quickly released as a single to tie in to the popularity of both Vanilla Ice and the Turtles. This single became the first nail in the coffin of Ice’s career.

The sequel came out at the height of the Turtles popularity, and suffered for it. The violence was toned down and the Turtles’ distinctive weapons were minimized. There was an eye towards merchandising as well, including an awkward cameo by the then-briefly popular Vanilla Ice, who sang “Ninja Rap” (“Go Ninja, Go Ninja, GO!”) during a fight scene at a club. The song was quickly released as a single to tie in to the popularity of both Vanilla Ice and the Turtles. This single became the first nail in the coffin of Ice’s career.

What about the plot? Well, Shredder figures out what caused the Turtles to mutate and uses it to mutate two bestial enemies for the Turtles before using it on himself to become “Super Shredder.”

The film cost more to produce than the first film ($25 million) and made less ($78 million), but was enough of a hit to garner another sequel—1993’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles III: Turtles in Time.

The film transported the Turtles back to feudal Japan, where they have to save a Japanese village from a British arms dealer. The film doubled its production budget back, but would prove to be the last Turtles film for 14 years, until 2007’s TMNT.

This was an attempt to create a new sequel to the film franchise using the current trend for computer generated animation. CGI suited the Turtles, making them fit into their surroundings just a bit better. The film focuses on the Turtles, who have drifted apart over the years since the last film. They have to reunite to prevent the world from being conquered.

This was an attempt to create a new sequel to the film franchise using the current trend for computer generated animation. CGI suited the Turtles, making them fit into their surroundings just a bit better. The film focuses on the Turtles, who have drifted apart over the years since the last film. They have to reunite to prevent the world from being conquered.

What about Eastman and Laird? Well, they drifted apart, too. Eastman moved to California, Laird to Massachusetts. Both became involved in creator rights in different ways. Eastman started up Tundra, a creator-friendly company that published Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell (which we’ll talk about later), James O’Barr’s The Crow (which we’ll talk about later), and Mike Allred’s Madman (which I wish we were talking about later) and would buy Heavy Metal magazine (which we talked about already). Laird created the Xeric Foundation in 1992, established to give money to organizations that promote literacy and grants to talented creators to help fund their comics.

In 2000, Laird bought out most of Eastman’s right to the Turtles, with the whole of Eastman’s rights being bought in 2008. Laird remained involved with the Turtles until he was involved in a deal with Nickelodeon for the characters, a deal worth $60 million dollars, finalized in 2009. Part of the deal was that Laird would still be able to create up to 18 TMNT comics a year, Eastman still owns Heavy Metal, and was married to former Penthouse Pet of the Year and B-Movie Queen Julie Strain. Last year, Eastman was involved in the Turtles reboot from IDW as well.

Eastman is also supposed to be involved with Michael Bay’s controversial TMNT revamp, Ninja Turtles. The project garnered a fair bit of controversy last year when Bay admitted making some major changes to the concept, including making the turtles older and turning them into aliens. Eastman’s involvement has seemed to alieviate many longtime fans’ fears, but the new take might bring some new fans to the franchise.

So, there you go, the American success story. A joke amongst friends turns into an indelible piece of international pop culture. Cowabunga, dude.

Next, we begin a string of great, if somewhat underrated, comic book film adaptations.