In a multi-part series, Comic Book Film Editor William Gatevackes will be tracing the history of comic book movies from the earliest days of the film serials to today’s big blockbusters and beyond. Along with the history lesson, Bill will be covering some of the most prominent comic book films over the years and why they were so special. This time, we’ll focus how Star Wars went from not being a comic book movie to being a comic book movie.

It seems hard to believe that there ever was a time when putting the words Star Wars on something wasn’t the equivalent of printing money. But that wasn’t always the case. As a matter of fact, the thought of putting up the first Star Wars film was a dicey proposition.

You had George Lucas, a talented yet unproven writer/director with only two films to his name—THX1138 and American Graffiti. He was creating the big space opera that many studio executives didn’t get. It promised to be a big budget production, which scared off many studios. Theaters weren’t that willing to carry the movie, considering that the biggest stars on screen were Alec Guinness and Peter Cushing. Sure, you had Eddie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds daughter in the film and James Earl Jones doing a voice, but it wasn’t like you had Paul Newman and Robert Redford in the film. Some theater owners had to be blackmailed into carrying the film by Fox threatening to withhold the then highly anticipated adaptation of Sidney Sheldon’s The Other Side of Midnight.

You had George Lucas, a talented yet unproven writer/director with only two films to his name—THX1138 and American Graffiti. He was creating the big space opera that many studio executives didn’t get. It promised to be a big budget production, which scared off many studios. Theaters weren’t that willing to carry the movie, considering that the biggest stars on screen were Alec Guinness and Peter Cushing. Sure, you had Eddie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds daughter in the film and James Earl Jones doing a voice, but it wasn’t like you had Paul Newman and Robert Redford in the film. Some theater owners had to be blackmailed into carrying the film by Fox threatening to withhold the then highly anticipated adaptation of Sidney Sheldon’s The Other Side of Midnight.

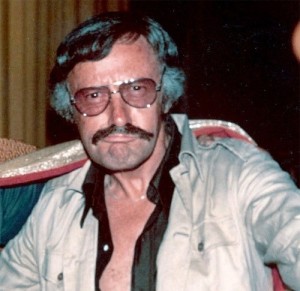

So, before it came out, Star Wars wasn’t a slam dunk guaranteed success. But Lucas and his staff came up with an ingenious way of promoting the film—comic books. They created a pitch and presented their case to Marvel Comics publisher Stan Lee. Marvel would get the rights to publish a comic book based on Star Wars with the only catch being that they would have to publish two issues of the six-issue adaptation of the film before the film was released (to generate buzz amongst comic fans for the film). Lee, being a prudent businessman, did the smart and logical thing.

So, before it came out, Star Wars wasn’t a slam dunk guaranteed success. But Lucas and his staff came up with an ingenious way of promoting the film—comic books. They created a pitch and presented their case to Marvel Comics publisher Stan Lee. Marvel would get the rights to publish a comic book based on Star Wars with the only catch being that they would have to publish two issues of the six-issue adaptation of the film before the film was released (to generate buzz amongst comic fans for the film). Lee, being a prudent businessman, did the smart and logical thing.

He told them no. He flat out denied their request.

Perhaps it was due to Lee’s aversion to licensed properties (Roy Thomas had to beg him to agree to license Conan the Barbarian, a property that became a best-seller for Marvel). Or maybe Lee knew that Marvel, a company that was experiencing an uncertain future due to declining sales and a shaky corporate parent in the Cadence Industries, wouldn’t want to risk taking a chance on a science-fiction property (which didn’t sell well in the renewed age of the superhero comic) adapted from a film (which were seldom high sellers, even if the source film was a hit, which there was serious doubt that Star Wars would be). So Lee said no and when he killed an idea, the idea stayed dead.

Unless, that is, Roy Thomas could convince him otherwise.

Unless, that is, Roy Thomas could convince him otherwise.

Roy Thomas was a respected writer and editor and was Stan’s handpicked successor to become Editor-In-Chief at Marvel when Lee stepped down from the position. Thomas had just resigned as EIC himself to focus on writing when Lucas contacted him through a mutual acquaintance. The acquaintence set up a meeting between Thomas and Lucas’ right hand man, Charley Lippincott, to try once more to get the comic book up and running. Thomas agreed to listen to the pitch with little intention of approving the concept. First, he wasn’t EIC anymore, so he couldn’t get it approved without Stan Lee’s approval and, second, Stan had already passed on it, which made it essentially a moot issue.

Lippincott began telling Thomas the plot of the film, armed with the now famous production drawings of Ralph McQuarrie. He got halfway through the presentation when Thomas stopped him. He had heard all he needed to hear.

Thomas was sold. He saw potential in the story. The film might not do that good, but it would make a great comic book. He immediately went to Stan and convinced him to change his mind. He did and same as Stan rejecting an idea would kill it dead, his approving an idea meant it got published—even if the people working at Marvel were dead against it.

Thomas was sold. He saw potential in the story. The film might not do that good, but it would make a great comic book. He immediately went to Stan and convinced him to change his mind. He did and same as Stan rejecting an idea would kill it dead, his approving an idea meant it got published—even if the people working at Marvel were dead against it.

How did the comic do? I’ll let Jim Shooter, editor at Marvel at the time, explain:

The first two issues of our six (?) issue adaptation came out in advance of the movie. Driven by the advance marketing for the movie, sales were very good. Then about the time the third issue shipped, the movie was released. Sales made the jump to hyperspace.

And the title kept on selling. The film was a cultural phenomenon. People lined up around the block just to get into a showing from the day it was released. Theaters that wanted to have nothing to do with the film were now clamoring to house the film as it expanded into wider release. And this adaptation that almost never got made ended up saving Marvel.

Star Wars has been published in comics form ever since. Marvel published 107 issues of the series over the next nine years. It adapted Empire Strikes Back in its pages and gave fans its first look at Jabba the Hutt (who Marvel artists drew to resemble a green rabbit/walrus hybrid, not the slug-like Jabba from the films). Marvel also published an adaptation of Return of the Jedi in a separate miniseries. This miniseries got Marvel in a bit of hot water when Luke Skywalker himself, comic fan Mark Hammill, walked into a comic shop and found that some enterprising comic shop owner had started selling the miniseries before not only the predetermined street date but also before the sequel hit movie screens. Ironic that Marvel was getting into trouble for something the studio made them do at the start of the relationship, isn’t it?

The success of the Star Wars comic book not only kept Marvel afloat during a tough time, but allowed them to develop the right creators on the right titles that would give them the lead in market share. Pairings such as Chris Claremont and John Byrne on the X-Men, Frank Miller on Daredevil, Byrne on Fantastic Four, and Walt Simonson on Thor.

The Star Wars license is now at Dark Horse Comics and is a great contributor to that company’s bottom line. But none of it would have happened if Roy Thomas hadn’t taken a chance on the property years earlier. Star Wars might not have been adapted from a comic, but it did appear in comics before it appeared in movie theaters. And I think that’s worthy of inclusion here.

Next up, you will believe a man can fly. Because the actor playing the man is exceptionally super.

Bonus, another form of Star Wars marketing from the era!

Fun fact. Marvel’s first version of Jabba was based on an alien that was originally supposed to be seen in the Cantina scene, but was edited out of the final version. You can see him in the rough cut of the scene that is one of the extras on the new STAR WARS blu-ray.