In a multi-part series, Comic Book Film Editor William Gatevackes will be tracing the history of comic book movies from the earliest days of the film serials to today’s big blockbusters and beyond. Along with the history lesson, Bill will be covering some of the most prominent comic book films over the years and why they were so special. This time, we’ll focus on the first forays of the underground comix scene into the world of film.

The counterculture movement took hold of America in the mid-to-late 1960s and changed the country forever. The youth of the country, angry that they were drafted to fight in a war they didn’t agree with, angry that they had to live in a world full of prejudice and hatred, angry that “the establishment” set up by their mothers and fathers forced them to conform to an image that they were not comfortable with, rebelled.

The counterculture movement took hold of America in the mid-to-late 1960s and changed the country forever. The youth of the country, angry that they were drafted to fight in a war they didn’t agree with, angry that they had to live in a world full of prejudice and hatred, angry that “the establishment” set up by their mothers and fathers forced them to conform to an image that they were not comfortable with, rebelled.

Whether it was through organized protests or following Timothy Leary’s advice to “tune in, turn on, and drop out,” the youth of America showed their disdain for the way things were in anyway possible.

This spirit of rebellion spilled over to the arts. The movement allowed musical artists like the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and Bob Dylan a chance to grow and experiment. It also allowed acts such as Jimi Hendrix, the Doors, Janis Joplin, and the Grateful Dead to find an audience that they might not have found ten years earlier. It allowed films as diverse as Easy Rider and Bonnie and Clyde to be made. And its presence was even felt in the world of comic books.

M uch like the counterculture movement itself acted as a rebellion against the geopolitical mainstream structure, underground comix rebelled against the restrictive nature of mainstream comics. The world of mainstream comics were made to be safe and homogenized by the oppressive eye of the Comics Code Authority. While female heroes could wear skin-tight bodysuits or costumes that showed a whole bunch of leg, sex was verboten in the mainstream. Any mention of drugs, even if the story was mandated by the Federal Government, as was the case in Amazing Spider-Man #96-98 (1971), meant the Code wouldn’t approve. Violence up to a point was okay, but, thanks mostly to the legacy of EC Comics, graphic horror and certain occult themes were forbidden.

uch like the counterculture movement itself acted as a rebellion against the geopolitical mainstream structure, underground comix rebelled against the restrictive nature of mainstream comics. The world of mainstream comics were made to be safe and homogenized by the oppressive eye of the Comics Code Authority. While female heroes could wear skin-tight bodysuits or costumes that showed a whole bunch of leg, sex was verboten in the mainstream. Any mention of drugs, even if the story was mandated by the Federal Government, as was the case in Amazing Spider-Man #96-98 (1971), meant the Code wouldn’t approve. Violence up to a point was okay, but, thanks mostly to the legacy of EC Comics, graphic horror and certain occult themes were forbidden.

The underground comix scene, inspired by the spirit of the counterculture movement, was started by artists who were looking to discuss topics that meant something to them. Drug humor, sexual situations, and other topics that would never be allowed in newsstand comics found a home in the underground scene.

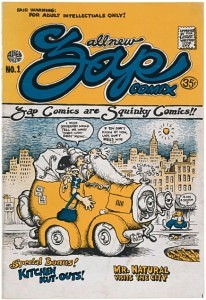

Robert Crumb was an artist who also found a home in the underground scene. He started work as an artist in such mainstream companies as Topps and American Greetings before selling some cartoons to various underground newspapers of the day. His success in this market encouraged Crumb to move out to San Francisco. Shortly thereafter, he published his first comic book, Zap Comics and the rest is history.

Robert Crumb was an artist who also found a home in the underground scene. He started work as an artist in such mainstream companies as Topps and American Greetings before selling some cartoons to various underground newspapers of the day. His success in this market encouraged Crumb to move out to San Francisco. Shortly thereafter, he published his first comic book, Zap Comics and the rest is history.

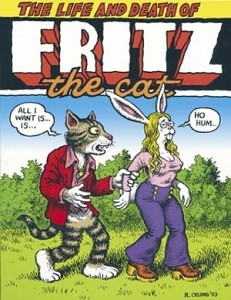

Crumb is a legendary and polarizing figure in the world of comics. His artistry has garnered him much respect, including a spot on 2006-2007’s Masters of American Comics exhibit and entry into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame. But his subject matter, usually his unfiltered id recorded on the page had garnered strong criticism from women (who find his portrayal of women misogynistic) and African-Americans (who find the way he draws blacks racist). Nonetheless, his motto of “Keep On Trucking” and his characters such as Mr. Natural and Fritz the Cat has logged him into a bizarre section of Americana. Not many cartoonist, underground or not, have a documentary made of their life and work. Crumb has two–The Confessions of Robert Crumb (1987) and Crumb (1994).

Fritz the Cat was the character that caught the attention of animator Ralph Bakshi. Bakshi was an animator for Terrytoons (the studio most famous for Heckle and Jeckle, Mighty Mouse, and Deputy Dawg) who felt stifled working under the constraints and censorship of the studio system. Through Fritz, he felt a bond with Crumb and believed Fritz could be the vehicle for him to let loose of those constraints and censorship.

Fritz the Cat was the character that caught the attention of animator Ralph Bakshi. Bakshi was an animator for Terrytoons (the studio most famous for Heckle and Jeckle, Mighty Mouse, and Deputy Dawg) who felt stifled working under the constraints and censorship of the studio system. Through Fritz, he felt a bond with Crumb and believed Fritz could be the vehicle for him to let loose of those constraints and censorship.

After a weird and frustrating back and forth with Crumb over the rights (high point of which was Crumb giving Bakshi his sketchbooks as a style guide, a low point being Crumb refusing to sign a contract), Bakahi and his producer Steve Krantz eventually got the rights to make the film through Crumb’s then wife Dana through her power of attorney.

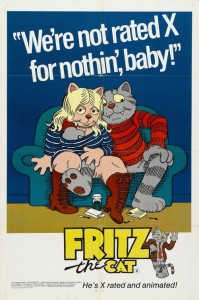

The film had a hard time finding a distributor due to the lack of famous voices in the cast and the graphic sex depicted on screen. Warner Brother originally agreed to fund the film but backed away due to the concerns mentioned above. Grindhouse distributor Cinemation Industries agreed to distribute the film, even after the film received a X rating from the MPAA.

The film had a hard time finding a distributor due to the lack of famous voices in the cast and the graphic sex depicted on screen. Warner Brother originally agreed to fund the film but backed away due to the concerns mentioned above. Grindhouse distributor Cinemation Industries agreed to distribute the film, even after the film received a X rating from the MPAA.

The film has taken on a cult status over the years, garnering many dedicated fans. One person who wasn’t a fan was Crumb himself. The artist had serious issues with how his character was portrayed on screen, commenting on everything from Fritz’s voice (which was done by the Electric Company’s Skip Hinnant) to the new content. Crumb had the last word on the subject. In Fritz’s last appearance, which was published shortly after the film came out, he portrayed the character as a Hollywood sell-out that gets killed via an ice-pick to the head delivered by an ex-girlfriend. That makes a pretty definitive statement of what Crumb thought of the film.

Even though Crumb was not interested in seeing any more of Fritz the Cat up on the big screen, that didn’t stop producer Krantz from delivering a sequel in 1974 called The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat.

Ralph Bakshi was not involved in this effort, as it was directed by Robert Taylor and written by Taylor, Fred Halliday, and Eric Monte. Bakashi would go on to become a legendary name in alternative animation, creating films such as American Pop, Fire and Ice, and Cool World.

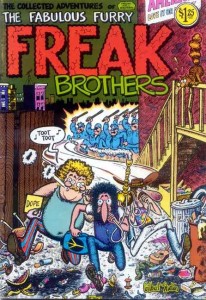

Fritz the Cat wasn’t the only Robert Crumb character to reach the big screen. The year after Fritz the Cat arrived on the big screen, Crumb’s Mr. Natural joined Gilbert Sheldon’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers in a film that was even more underground than Bakshi’s film, and with a couple more X’s in the rating.

Up in Flames is a porn movie loosely based on Shelton’s characters. The plot, according to IMDB I feel the need to point out, deals with the brothers having to get odd jobs in order to pay the rent. Each job they take inevitably leads to sexual situations. One of the boy’s employers is Mr. Natural, who in the movie plays the owner of a health food store.

Up in Flames is a porn movie loosely based on Shelton’s characters. The plot, according to IMDB I feel the need to point out, deals with the brothers having to get odd jobs in order to pay the rent. Each job they take inevitably leads to sexual situations. One of the boy’s employers is Mr. Natural, who in the movie plays the owner of a health food store.

It goes without saying that this film is unauthorized and not approved by either Sheldon or Crumb. Gone is the Freak Brothers’ trademark drug humor. Two out of the three brothers have their name changed from the original comic book, and the one whose name remains the same, Fat Freddy, is not fat at all. And the octogenarian Mr. Natural is played by the films 30-something director wearing a fake beard.

Plans are afoot to bring the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers back to the big screen in a more legitimate way. Production began in 2006 of a stop-motion, clay figure animation film version of the characters called Grass Roots, done by people who have worked on Wallace and Gromit and Chicken Run for Aardman. A test reel hit the web in 2006:

As of 2009, work was still being done on the film, which adapts one of Sheldon’s original stories for the screen.

Next up, we make the argument for Star Wars being a comic book movie.