Last weekend, the comedy Black Dynamite opened in limited release to positive reviews. Although a loving spoof of 1970s blaxploitation films, no real knowledge of the genre is needed to enjoy it. Of course, if it does ignite an interest in the actual films, one will find a fascinating group of films that uniquely capture a cross-section of America in that decade. Here’s a quick overview of the genre. Read with your Netflix queue open.

If blaxploitation was a revolution, then Melvin Van Peebles was its Che Guevara. His first two films – the interracial romance The Story Of A Three Day Pass (1968) and the whiteface satire Watermelon Man (1970) – were just warmups for the lobbed hand grenade that was 1971’s Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song, the movie that would solidify the blaxploitation tone. Many mainstream critics, both black and white, would denounce the movie as containing nothing but negative stereotypes. But none less than Huey P. Newton, founder of the radical Black Panthers, would champion the film, devoting a full issue of the organization’s magazine to it.

Hollywood also noticed. It wasn’t the political message that intrigued studios, but the fact that the film managed to make a little over $4 million at the box office. The message was clear. African American audiences wanted to see African-American heroes on the big screen. And thus was a whole new wave of films born.

Shaft has a lot of history going for it. It was the second film from Gordon Parks, the first black director hired by a major motion picture studio, MGM. It had an unknown actor make his film debut in a lead role that would catapult him to stardom. Its composer would become the first African-American to win the Academy Award for Best Original Score. There is no denying that Shaft is an important milestone in black cinema.

But can it be considered a true blaxploitation film? Financed by a major studio, its hero is a “black private dick who’s a sex machine with all the chicks,” not the pimps, hoods and anti-heroes usually connected with the genre. If anything, its origins in a series of detective novels written by former newspaperman Ernest Tidyman place it closer to pulp and noir territories. However, it helped reinforce to Hollywood executives the lesson that Van Peebles Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song had taught just a few months earlier- there was money to be made by catering to black audiences.

Pimps, Hoods, Outlaws And Tough Guys

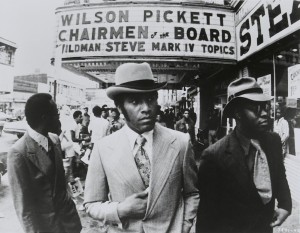

It took Gordon Park’s son, Gordon Parks Jr. to really lead the blaxploitation charge with 1973’s Super Fly, a tale of a Harlem drug dealer trying to do straight. The Mack (1973), starring Max Julien and Richard Pryor, was seen by its creators as more social commentary than exploitation. But both films proved that pimps were box office gold and soon there were plenty of imitators.

Fred “The Hammer” Williamson would play characters on both sides of the law. In The Hammer (1972), he would be a boxer stuck with a crooked manager, but would be making a move to take over all organized crime in Harlem in Black Caesar (1973). (You can skip Black Caesar’s hastily thrown together sequel Hell Up In Harlem (1974).) Williamson also managed to transplant his tough guy persona to the Old West with the films The Legend Of Nigger Charley (1972), The Soul Of Nigger Charley (1973), Boss Nigger (1974) and Bucktown (1975).

Fred “The Hammer” Williamson would play characters on both sides of the law. In The Hammer (1972), he would be a boxer stuck with a crooked manager, but would be making a move to take over all organized crime in Harlem in Black Caesar (1973). (You can skip Black Caesar’s hastily thrown together sequel Hell Up In Harlem (1974).) Williamson also managed to transplant his tough guy persona to the Old West with the films The Legend Of Nigger Charley (1972), The Soul Of Nigger Charley (1973), Boss Nigger (1974) and Bucktown (1975).

Former football star Jim Brown found a measure of success as a supporting actor in films like Rio Conchos, The Dirty Dozen and Ice Station Zebra, but would be elevated to star status with films like Slaughter (1972), Slaughter’s Big Rip Off (1973) and Black Gunn (1974).

Pam Grier wasn’t just one of the blaxploitation’s biggest stars, she also was one of the 1970s biggest female box office draws, behind only Barbara Streisand and Liza Minnelli. As tough an asskicker as she was (and still is) beautiful, Grier exploded across screens with the one-two punch of Coffy (1973) and Foxy Brown (1974). But her lesser known work is worth checking out including The Big Doll House (1971), Friday Foster and Sheba, Baby (both 1975). If it seems like she’s beating on the same guy in film after film, you’re probably seeing Sid Haig, who has appeared in five Grier films, mostly as bad guys.

The fact that Tamara Dobson falls a distant second to Grier is not fault of her own, but a testament to Grier’s stardom. The six-foot, two-inch tall model turned actress’s two Cleopatra Jones films are definitely worth watching and were popular enough to serve as the basis of a short parody in Kentucky Fried Movie (1977)-

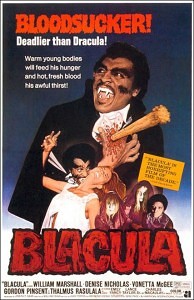

Almost from the beginning of the blaxploitation craze, producers began cranking out horror movies with predominantly black casts. The first and still the best known of this subgenre is 1972’s Blacula, which manages to capture a bit of the vibe of the cycle of horror films put out by Britain’s Hammer Studios a few years previously. A success, it quickly launched a sequel one year later in which William Marshall’s African vampire Mamuwalde squares off against none other than Pam Grier. Vampires would also show up in 1973’s Ganja And Hess.

Zombies would bedevil the cast of Sugar Hill (1974), while Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll And Mister Hyde got remade as Dr. Black And Mr. Hyde. Meanwhile, 1974’s The Beast Must Die grafts its werewolf story on to the template of the classic short story “The Most Dangerous Game” and then pauses midstream to allow the audience time to figure out who the werewolf really is. Blackenstein (1974) went so far as to hire Ken Strickfadden, who created all the unique electrical apparatus for the classic 1931 Frankenstein, to shock its own monster to life.

Even more recent horror wasn’t exempt from a blaxploitation makeover. AIP’s Abby (1974) was a little too close to The Exorcist for Warner Brothers’ lawyers, who threatened to sue the indie studio. AIP withdrew the $200,000 picture, but it managed to gross over $4 million its opening week.

The Blaxploitation craze was just like any other. It started to fade out by the mid-1970s. But its spirit lives on. Cinematically, its influence can be seen in films like Tarantino’s Jackie Brown and the works of Mario (son of Melvin) Van Peebles. And we will undoubtedly see more films bearing its imprint as well.