Screenplay by Michael J. Bassett

Screenplay by Michael J. Bassett

Undated Draft

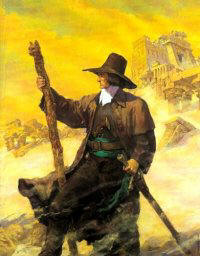

In 1928, a good five years before the first tales of a certain Cimmerian swordsman by the name of Conan saw print, the pulp magazine Weird Tales published a novelette by that character’s creator Robert E. Howard. Titled “Red Shadows,” it introduced the character of Solomon Kane, a Puritan swordsman from Devon, England who travelled the world of the sixteenth century fighting evil wherever he found it. As the world was still fairly unexplored at this time, the evil often took the supernatural form and Kane would find himself pitted against werewolves, witches, vampires, ghosts and even a Lovecraftian horror in one tale, making him one of, if not the first of, modern literature’s monster hunters. If one subscribes to the notion that all fictional characters reside in a shared universe (see Alan Moore’s League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen’s appendixes for a better example of this) than it can be honestly said that Solomon Kane was kicking vampire butt long before Abraham Van Helsing was even a glimmer in his father’s eye.

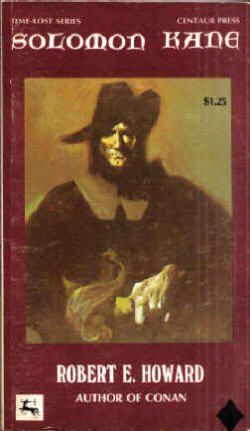

Howard wrote twelve stories and three poems about Solomon Kane before his untimely death in 1936, but even some of those, such as “The Castle Of The Devil” And “Children Of Asshur” are just (unfortunately) unfinished fragments. These stories were collected into three volumes by Centaur Press in the late 1960s and again, with the inclusion of two other fragment stories, by Del Rey Books in 2004. During the 1970s, Solomon Kane enjoyed an existence as a backup feature in Marvel Comics’ Savage Sword Of Conan magazine and even got his own mini-series, The Sword Of Solomon Kane, in 1985, as well as a few independent comic company one-shots in the ‘90s. Although creators John Ostrander and Tim Truman have (to the best of my knowledge) never stated so, Solomon Kane would appear to be a major influence on their comic character Grimjack.

For the most part though, Kane seemed to be fantasy literature’s forgotten son, a guilty pleasure known only to diehard Howard readers and fans of esoteric pulp fiction. Motion pictures, which flirted with his literary brother Conan in the early 1970s and fully embraced him in the two 1980s films, pretty much ignored Kane. Granted, a few films came close. The 1973 Hammer Studios film Captain Kronos, Vampire Hunter came the closest with its depictions of a swashbuckling hero (Horst Janson) fighting vampires with swordplay in 17th century Europe, although Janson’s blonde, womanizing Kronos is a far cry from the dark-haired, Puritan Kane. A silhouetted figure resembling Kane is seen gunning down the two title characters in the 1975 film Vampyres, Daughters Of Dracula, but its presence is never explained (like a lot of things in that film). The 1985 Japanese anime Hero D- Vampire Hunter (released in the US in 1992 as Vampire Hunter D) featured a main character whose look – black clothing and cape, wide-brimmed hat and long black hair – was clearly influenced by Kane, although Hideyuki Kikuchi, author of the series of books upon which the movie and its sequel were based and a self-professed Hammer films fan has stated that his D is a combination of Captain Kronos and Christopher Lee’s version of Dracula and has yet to acknowledge Solomon Kane as a visual model for D.

For the most part though, Kane seemed to be fantasy literature’s forgotten son, a guilty pleasure known only to diehard Howard readers and fans of esoteric pulp fiction. Motion pictures, which flirted with his literary brother Conan in the early 1970s and fully embraced him in the two 1980s films, pretty much ignored Kane. Granted, a few films came close. The 1973 Hammer Studios film Captain Kronos, Vampire Hunter came the closest with its depictions of a swashbuckling hero (Horst Janson) fighting vampires with swordplay in 17th century Europe, although Janson’s blonde, womanizing Kronos is a far cry from the dark-haired, Puritan Kane. A silhouetted figure resembling Kane is seen gunning down the two title characters in the 1975 film Vampyres, Daughters Of Dracula, but its presence is never explained (like a lot of things in that film). The 1985 Japanese anime Hero D- Vampire Hunter (released in the US in 1992 as Vampire Hunter D) featured a main character whose look – black clothing and cape, wide-brimmed hat and long black hair – was clearly influenced by Kane, although Hideyuki Kikuchi, author of the series of books upon which the movie and its sequel were based and a self-professed Hammer films fan has stated that his D is a combination of Captain Kronos and Christopher Lee’s version of Dracula and has yet to acknowledge Solomon Kane as a visual model for D.

More recent films such as Brotherhood Of The Wolf and the first Pirates Of The Caribbean featured settings and scenarios befitting a Solomon Kane tale but without the presence of said character. Finally, in the winter of 2001, a film version of Solomon Kane was announced by the producers of The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen. The plot of this film would deal with Kane, a descendant of Conan, seeking revenge on a shape-changing sorcerer for the murder of his family in colonial America. While Howard made a passing reference to Kane once visiting the Virginia colonies and fighting Indians there in one of his stories, the idea of setting the film in Colonial America just seems like a lazy way to explain Kane being a Puritan (rather than doing some research on the Puritans in England instead) and the idea of the shape-changing sorcerer villain seems recycled from a Conan movie, much like the bland Kevin Sorbo vehicle Kull The Conqueror (also based on a Robert E. Howard character). Also, making the solitary wandering Kane a family man and a descendent of Conan shows an obvious unfamiliarity with the source material. Fortunately, and perhaps fueled by League’s dismal performance, this B-movie camp version never came into being, and it looked like Solomon Kane would be ignored by the motion picture industry for good.

But it was not to be, because in January 2008, production started on a Solomon Kane movie starring James Purefoy in the title role. The film’s script by Michael J. Bassett solves what could have been an obstacle in creating an original first story about this character by basically giving an origin story to a character who previously did not have one. Granted Howard’s stories and poems have made references to Kane’s past, including his birthplace in Devon, serving in the British Navy against the Spanish Armada, running afoul of the Spanish Inquisition and even a brief career as a pirate captain, but they never tell why he came to be the man who is in introduced in “Red Shadows”- a Puritan swordsman (itself something of a contradiction as Puritans are often thought of as pacifists, not expert fencers who are also handy with flintlock pistols) who staunchly protects the innocent and is the eternal foe of all unexplained and supernatural evils. Bassett’s script shows how Kane gets to be this heroic figure and why he does what he does.

The script begins with Kane as a captain in the British Navy, but something of a bloodthirsty aristocrat (“a murderous dandy” as the script puts it) who delights in battle, killing and the gaining of riches by looting. On a rescue mission against native warriors on the North African coast, Kane and his crew stumble upon a castle rumored to be teeming with treasure. Fighting his way in, Kane instead discovers a gateway to Hell, whose demons kill his men. The demon’s leader, called The Devil’s Reaper, tells Kane that it has come for his soul, which has been sentenced to Hell for the Englishman’s life of bloodshed and killing, especially the murder of his own brother, Marcus. It was the accidental murder of this arrogant and brutish older sibling, as well as a falling out with his father, that caused the young Kane to abandon a life in the priesthood and flee home to join the Navy.

The script begins with Kane as a captain in the British Navy, but something of a bloodthirsty aristocrat (“a murderous dandy” as the script puts it) who delights in battle, killing and the gaining of riches by looting. On a rescue mission against native warriors on the North African coast, Kane and his crew stumble upon a castle rumored to be teeming with treasure. Fighting his way in, Kane instead discovers a gateway to Hell, whose demons kill his men. The demon’s leader, called The Devil’s Reaper, tells Kane that it has come for his soul, which has been sentenced to Hell for the Englishman’s life of bloodshed and killing, especially the murder of his own brother, Marcus. It was the accidental murder of this arrogant and brutish older sibling, as well as a falling out with his father, that caused the young Kane to abandon a life in the priesthood and flee home to join the Navy.

Kane narrowly escapes the Reaper’s castle and returns to England where he renounces violence and spends a year in the sanctuary of a monastery. During this time, he covers himself with tattoos and scars of protective spells and researches numerous arcane and religious tomes, always fearing that the forces of hell are waiting to snatch him up. Worried that this darkness will consume him and his monks, the monastery’s abbot politely orders Kane to leave.

With nowhere to go, Kane wanders the English countryside, finding it rife with wandering brigands. After being attacked by some of these bandits, he is found and nursed back to health by the Crowthorns, a family of Puritans fleeing religious persecution by going to America. Kane agrees to accompany them to the coast, but says he will not sail with them for a new life in America as he needs to redeem his old life first.

Their journey becomes hindered by a landscape of pillaged villages, rampaging witches and an ever-growing, and now-organized, army of raiders. Inscribed with mystical insignias and almost demonic in nature, they are conquering everything in their path. Evil, forces seem to be growing stronger and are massing in the west under the leadership of the sorcerer Malachi and his general, The Overlord, a masked being displaying a supernatural control over his troops.

When the Crowthorns are murdered and the daughter, Meredith, is captured by the raiders, Kane’s old person re-emerges and he slays the attackers. Vowing to her dying father to rescue Meredith, as that act may redeem his soul, Kane sets out into a haunted countryside of mad priests, ghouls and more demonic raiders. At some point, he is erroneously told that Meredith is dead and falls into a depressed drinking binge in a raider-occupied village. Kane is captured in this state and is crucified (!) before the villagers. He survives the ordeal, however, aided by the appearance of Meredith in the village, and is now gifted with the ability to see demons in disguise. This comes in handy when he is rescued and healed by a group of rebels.

Aided by the rebels, Kane makes a climactic raid on his ancestral home of Axmuth Castle, the center of the raiders power and the prison of Meredith. Here, Kane must face not only Malachi and the Overlord, but deep secrets from his past and the return of the Reaper, whom Malachi has summoned to drag Kane to Hell.

I’ve often said when asked what a proper Solomon Kane movie should be like that it should pretty much be a Hammer film with a lot of action. Bassett’s script does just that, although it adds the influence of Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. The journey of Kane and the Crowthorns through the haunted English countryside reminded me very much of the journey of Max Von Sydow and the traveling actors through plague-ravaged Sweden. The mentions of bodies hanging from trees, old ruins and druidic circles also recalls some of the scenes of a young Gwynplaine (Conrad Veidt) trekking through the harsh wintery countryside in The Man Who Laughs. These are rather arty touches to a film that could have easily gone the route of a run-of-the-mill sword and sorcery flick.

I’ve often said when asked what a proper Solomon Kane movie should be like that it should pretty much be a Hammer film with a lot of action. Bassett’s script does just that, although it adds the influence of Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. The journey of Kane and the Crowthorns through the haunted English countryside reminded me very much of the journey of Max Von Sydow and the traveling actors through plague-ravaged Sweden. The mentions of bodies hanging from trees, old ruins and druidic circles also recalls some of the scenes of a young Gwynplaine (Conrad Veidt) trekking through the harsh wintery countryside in The Man Who Laughs. These are rather arty touches to a film that could have easily gone the route of a run-of-the-mill sword and sorcery flick.

The Hammer Studios influence cane be seen in later scenes involving a fight with villagers-turned-ghouls in a church’s catacombs, another with raiders in a moonlit graveyard and, of course, the tavern scene (a staple of Hammer films). I’m not sure if he’s dead or not, but it would be fun to see Ferdy Mayne as an innkeeper here.

Some people have grumbled on the internet about Kane not being portrayed as a Puritan. To that, all I can say is that while he’s not shown as being a Puritan at the start of the film, he is given Puritan garb by Meredith Crowthorn and his changed outlook on good and evil doesn’t exactly show that he isn’t a Puritan by the film’s end. Others may balk at Kane gaining the ability to see demons, something not in the original Howard stories, but I think this an acceptable “tweaking” of the character that is somewhat reminiscent of an ability possessed by the monster hunter class of characters in the World of Darkness role-playing games. So it makes sense that Kane, a monster hunter, would have this power. As he even tells Meredith at one point, “There are evil creatures walking this earth, Meredith. They bring such pain and suffering and there was never a man who could fight them. But I can. I can. It is my gift and I will hunt them down and send each and everyone back to hell.” That speech, for me, is very true to the nature of Howard’s creation.

Finally, some fans may complain that the film doesn’t adapt anything from Howard’s stories, especially Kane’s mystical cat-headed staff and the African witch doctor who gave it to him, N’Longa. To that, I have to say that most of the stories are pretty short and would need a lot of padding and tweaking to become feature length film material. Sure, I’d love to see film versions of “Red Shadows,” “The Hills Of The Dead” and maybe even a finished version of “The Castle Of The Devil” and “Children Of Asshur,” but that’s what sequels are for. And if this ultimately faithful script is followed closely than hopefully that’s what fans can expect and get.

Note: Rich Zeszotarski would like to thank Bret Blevins and Michael W. Kaluta whose conversations concerning Solomon Kane have certainly “fanned the flames” of his fervor for this character. Also, big thanks to Rich Drees, who knows what a huge fan Rich is and nudged him into reading this script even though he was afraid it would be crap.

[…] Script Review: SOLOMON KANE […]

Having seen the movie, I believe it is very faithful to the script. As a long time Solomon Kane fan, I had concerns about the whole “origin” aspect of the film, but now I agree that it was a good idea and was executed well. Yes, there are some aspects of the story that seem to conflict with things said in some of the stories, but at the end of the film the character that remains is the Solomon Kane of the stories. I’d be glad to see sequels if they are as good as this movie.