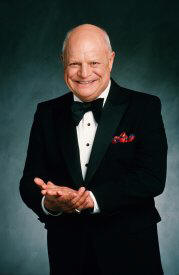

When we first see legendary entertainer Don Rickles he is sitting backstage in his dressing room at the Stardust Hotel, waiting to hit the boards. Looking a bit frail, his hand shakes ever so slightly as he ties his bow tie- no clip-on for this old timer. Sipping tea, he discusses the current baseball season with his publicist. Taking a slow walk from dressing room to the wings of the stage, he stops briefly to talk to a stage hand he recognizes.

When we first see legendary entertainer Don Rickles he is sitting backstage in his dressing room at the Stardust Hotel, waiting to hit the boards. Looking a bit frail, his hand shakes ever so slightly as he ties his bow tie- no clip-on for this old timer. Sipping tea, he discusses the current baseball season with his publicist. Taking a slow walk from dressing room to the wings of the stage, he stops briefly to talk to a stage hand he recognizes.

But once he walks out on to the stage and the spotlight hits him, Rickles comes alive, evidencing an energy and spryness unhinted at in the time leading up to the start of his performance. The audience roars as he flings his famous insults at those who catch his eye as he predatorily prowls the stage. To be the recipient of his attentions is a badge of honor. No one cares that his jokes fly in the face of sensitivity or political correctness. As longtime friend Clint Eastwood tells us, “Don never lost his disdain for sensitivity.” Another interview subject, Chris Rock further elaborates on Rickles’ ability to entertain with insults- “Being funny is like being a pretty girl; you can get away with a lot of shit.”

But another interviewee, comic actor and director Chris Guest, warns against trying to dissect comedy, as such analysis only steals its subject’s ability to be funny. This admonishment leaves director John Landis in the quandary of having to create a document about a legendary funnyman without stripping him of his legend. But Landis succeeds in avoid just that pitfall, charting the rise of the Queens, New York-born comic without ever overanalyzing his subject. Interspersed with the biographical material is a wealth of other footage. We watch Rickles onstage at the Sands, ripping through his act, and in a rare moment of seriousness that doesn’t come off as sentimental or mawkish, breaking into song.

If you’re looking for some warts-and-all treatment of the comic, you will have to look elsewhere. Landis has assembled a loving tribute to the comic, with numerous show business colleagues, friends and admirers praising Rickles’ work or discussing its influence on them. There are testimonials from comedy legends like the Smothers Brothers and Carl Reiner and younger comics like Dave Atell and Sarah Silverman. Long time friend Bob Newhart contributes home video footage of the two on vacation with their wives.

Some of Rickles’ movie work is not illustrated through film clips of his acting but through the trailers for the films themselves. Landis admits that this was a cost saving measure – trailers are considered promotional material and therefore exempt to an extent from copyright protects he explained after the screening – but their use does go to show how Rickles was sold to the public as comic and actor.

Curiously, the rise of Rickles the performer shown here parallels the rise of Las Vegas as a city of top-notch nightclub entertainment. A friend of Frank Sinatra – whom he once spotted in the audience of one of his early shows and heckled, “Make yourself at home, Frank- hit someone!” – Rickles was at ground zero for the Vegas entertainment explosion of the early 1960s. And over four decades late, he managed to still be a top-drawing headliner in the town.