In many ways, Gus Van Sant’s Paranoid Park is a continuation of the themes and issues he has previously examined in 2003’s Elephant. Again we have teen characters with divorced or separated parents. Again we have characters whom move through their life of school, friends and family in a withdrawn state, seemingly uninterested in engaging in the world around them. Again we find Van Sant questioning what effect a fractured family can have on children. And again we have yet another fascinating film, with Van Sant managing to insulate himself into the world of today’s youth, taking us along as voyeurs of their raw, at times amoral and nihilistic world.

In many ways, Gus Van Sant’s Paranoid Park is a continuation of the themes and issues he has previously examined in 2003’s Elephant. Again we have teen characters with divorced or separated parents. Again we have characters whom move through their life of school, friends and family in a withdrawn state, seemingly uninterested in engaging in the world around them. Again we find Van Sant questioning what effect a fractured family can have on children. And again we have yet another fascinating film, with Van Sant managing to insulate himself into the world of today’s youth, taking us along as voyeurs of their raw, at times amoral and nihilistic world.

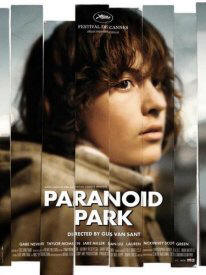

Alex (Gabe Nevins) is a teenager, aimlessly drifting his way through life and school, going through the motions, but not very concerned about what is going on around him. He seems unaware of the sexual signals being sent to him by his nominal girlfriend (Taylor Momsen). He even appears to be uninterested in the telling of his own story, turning his back on the camera repeatedly through the film. The only place where he truly seems to take an interest is at an underground skateboard park. While hopping a freight train one evening near the park with some other skateboarders, Alex becomes involved with the accidental death of a railroad yard security guard. As the police begin to investigate the incident, Alex struggles with his own feelings over the matter.

While using MySpace as a casting agency would seem like a ridiculous publicity stunt for most other films, here it has allowed Van Sant to once again find young, raw talent as yet untainted by the training the results in the usual performances seen in a mainstream film. Here, the actors have not over-analyzed their characters with an acting coach, searching for the perfect, and thus artificial, reading of each line of dialogue. When the occasional bit of delivered dialogue falls flat, it only emphasizes the flat and desensitized world of these teens.

In addition to these talented newcomers’ performances, Van Sant employs subtle tricks to visually accentuate the characters’ disconnect from the world around them. He has cinematographer Christopher Doyle, unusually away from the side of collaborator Wong Kar-Wai, stay away from deep focus shots, leaving backgrounds blurry and indistinct. Doyle’s work is augmented by Rain Kathy Li’s Super 8 photography whose soft, floating, dream-like quality captures the peace Alex finds at the skate park, the only peace he feels in his life.

In addition to these talented newcomers’ performances, Van Sant employs subtle tricks to visually accentuate the characters’ disconnect from the world around them. He has cinematographer Christopher Doyle, unusually away from the side of collaborator Wong Kar-Wai, stay away from deep focus shots, leaving backgrounds blurry and indistinct. Doyle’s work is augmented by Rain Kathy Li’s Super 8 photography whose soft, floating, dream-like quality captures the peace Alex finds at the skate park, the only peace he feels in his life.

More tone poem than crime story, the film’s structure – nonlinear, cutting back and forth across the storyline – mirrors Alex’s attempt to set what happened down on paper. Alex is another in a series of characters of Van Sant’s who are victims of divorced, absent or just plain inattentive parents. Although he is trying to come to terms with what has happened, he has no moral foundation for mentally and emotionally processing the events. It is no wonder that Alex has no ability to understand that he shares culpability for the watchman’s death. He doesn’t care because he doesn’t appear to have the ability to care. He doesn’t feel responsible because he has never had to have any responsibilities outside of taking care of himself. One would almost expect that such aimless, amoral and apathetic characters would come off as unlikable, but Van Sant manages to keep our sympathies for a majority of the cast – even the generation gap-clueless cops come off as decent enough – without ever letting the proceedings to become maudlin.