Although it confused critics and audiences in its initial 1982 release, Ridley Scott’s science-fiction noir Blade Runner remains, a quarter of a century later, not only one of the most important films in the director’s filmography, but one of the most important films of the decade. As the movie was rediscovered first on video tape and then a subsequent “Director’s Cut” released in 1992, many became immersed in the complex themes the movie explores. And now, director Ridley Scott has gone back to the film for a third, and presumably final time, for Blade Runner: The Final Cut, a digital restoration of the film which sees Scott taking the time to fix a few minor things that have bugged him over the years.

Although it confused critics and audiences in its initial 1982 release, Ridley Scott’s science-fiction noir Blade Runner remains, a quarter of a century later, not only one of the most important films in the director’s filmography, but one of the most important films of the decade. As the movie was rediscovered first on video tape and then a subsequent “Director’s Cut” released in 1992, many became immersed in the complex themes the movie explores. And now, director Ridley Scott has gone back to the film for a third, and presumably final time, for Blade Runner: The Final Cut, a digital restoration of the film which sees Scott taking the time to fix a few minor things that have bugged him over the years.

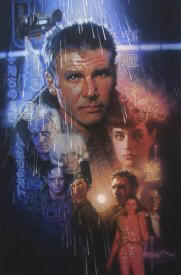

In Los Angeles of just a few decades hence, Harrison Ford stars as Deckard, a retired police detective or “blade runner” whose specialty was the hunting down and elimination of human-looking androids called replicants who have been built to handle jobs too dirty or dangerous for humans. Smart as humans, replicants have a habit of intellectually growing beyond the parameters of their intended design, gaining an autonomy that some would argue grants them their own personhood. As replicants are illegal on Earth and are only allowed off-planet in the “Outer Colonies,” Deckard is called back into service when four replicants, lead by Rutger Hauer in a career defining role, have illegally returned to Earth to ask their creator how much time they have left to live.

Right away, one is struck by the impressive restoration work done on the film. Every frame has been digitally cleaned and the end result is a picture quality that exceeds how the film has looked in any previous release, either theatrical or on home video. Ironically though, the clearer picture doesn’t dilute the film’s murky tone, but enhances it. The audience can now see in greater detail the grit and griminess that Scott and his production team, lead by noted futurist Syd Mead, coated the film with, heightening the verisimilitude of the rundown near-future Los Angeles.

Most of the changes that Scott has made are to clean up small production errors such as crew members accidentally appearing in the edges of some shots or cleaning up a few spots were the film’s optical effects betray the limitations of the visual effect technology of the time. A majority of these tweaks are so minor that they’ll by-pass all but the most rapid devotees of the film. There are one or two that are fairly obvious, such as the improvements done to the scene where a replicant played by Joanna Cassidy crashes through a series of plate glass while being pursued by Deckard.

Perhaps the only really disagreeable change comes right at the end when Batty releases a dove he was holding as he dies. In the film’s previous incarnations, we see the dove fly into a blue sky, even though it had been raining throughout the scene. This was due to a second unit camera crew shooting the shot of the dove rather quickly. The result was seen by some as a continuity error, though others, including myself, have viewed it as Batty’s life force/soul/what-have-you transcending the dirty world he had found himself in. Instead, the new shot with a digitally created background of the decaying Los Angeles skyline that the dove flies towards takes something away from Batty’s death and its deeper significance.

But while the film has been visually messaged here and there, it still contains the philosophical underpinnings that rise it above the multitude of other science-fiction films. “More human than human” is the motto of the film’s Tyrell Corporation and Blade Runner examines just what it is that makes one human. Is it the accumulation one’s memories and experiences? What if these memories were manufactured? And what is the moral implication of creating artificial life to serve as a slave class?

The future society of the movie refers to the elimination of replicants euphemistically as “retiring.” However, an argument could be made that since they have begun to develop their own consciousness that exceeds their original design specifications, the replicants are alive and that “retirement” is simply murder.

It is these questions that will continue to ensure that Blade Runner remains not just a classic of its genre, but of all cinema.