Perhaps the most recognizable character of 20th century popular literature is Superman. Rocketed to Earth as a baby to escape the destruction of his homeworld, Superman grows up to discover that his alien physiognomy has given him amazing powers on Earth, which he uses to fight for “Truth, Justice and the American Way!” Not only is Superman the most iconic of all comic book superheroes, he was also the first superhero to have been given his own cartoon series, which proved to be as influential as his four-color print adventures, thanks to the creative force behind the cartoons, the Fleischer Brothers Studio.

Perhaps the most recognizable character of 20th century popular literature is Superman. Rocketed to Earth as a baby to escape the destruction of his homeworld, Superman grows up to discover that his alien physiognomy has given him amazing powers on Earth, which he uses to fight for “Truth, Justice and the American Way!” Not only is Superman the most iconic of all comic book superheroes, he was also the first superhero to have been given his own cartoon series, which proved to be as influential as his four-color print adventures, thanks to the creative force behind the cartoons, the Fleischer Brothers Studio.

The Fleischer Brothers Studio was founded in 1921 by brothers Dave and Max Fleischer. Both brothers were artists who had worked various jobs in New York City- Dave as a cartoonist for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper, Max as an art editor for Popular Science Monthly. Max had long been interested in mechanical devices and it was through this interest that he developed the animation method known as rotoscoping. As the art of animation was still in its infancy, cartoon characters often moved jerkily. Max was looking for a method to make character animation more fluid. To that end, he devised, and built with the help of his brother Joe, the rotoscope- a light table upon which live action film was projected frame by frame, allowing an animator to trace the live action frame onto an animation cell.

The first cartoon the brothers produced using this method was 1918’s Out Of The Inkwell. In it, a clown, later to be named Koko, jumps out of an inkwell and performs somersaults. Koko was actually Dave in a clown suit, his actions filmed and then transformed into animation via the rotoscope. The initial cartoon was a success and soon the brothers were producing one “Out of The Inkwell” short a month for John R. Bray, an animation pioneer who had an exclusive contract to supply cartoons for Paramount Pictures. By 1921, the brothers had struck their own deal with Paramount and formed Fleischer Brothers Studios. A second series, “Song Car-Tunes” was started in 1924 and featured popular song lyrics for audiences to sing along with while local musicians provided accompaniment at each theatre.

The Fleischer studio moved to sound cartoons with their next series “Talkartoons,” launched in January 1930. By this time, Dave had taken over the majority of directing chores for the studio while Max ran the business side of things. They also hired another brother, Lou, to be in charge of music and sound recording. The Fleischer Studios’ next star, Betty Boop, would make her first appearance in the Talkartoon Dizzy Dishes (1930). Within a year, she graduated from a supporting character to the star of the Talkartoon series.

Much like Betty Boop first appeared in a previous cartoon before gaining her own series, the Fleischers’ next star would make his first appearance in Betty Boop’s series. The 1933 short Popeye The Sailor (released July 14) was used to introduce comic strip artist Elzie Segar’s crusty Thimble Theatre character onto the silver screen. Audience and critics reactions were so positive that the spinach-eating seaman launched his own cartoon series with the September 29, 1933 of I Yam What I Yam.

With the introduction of the Hayes Code in 1933, Dave Fleischer was forced to tone down some of the racier elements of the Betty Boop shorts. The studio continued to branch out though, with Dave launching the “Color Classics” series which adapted classic fairy tales. The series sported two innovations– the use of a multi-planed turntable for photographing the animation, resulting in a remarkable three-dimensional effect, and the use of two-strip color film (Rival studio Disney held a firm grip on the three-strip Technicolor process).

Although the studio was successful in turning out crowd-pleasing shorts, they had trouble making the transition to feature length cartoons. Their 1939 adaptation of Gulliver’s Travels, featuring a rotoscoped Sam Parker as Gulliver, lacked the spark of the studio’s one- and two-reel animated subjects and was met with critical indifference. A follow-up feature, Mister Bug Goes to Town (1941, re-released as Hoppity Goes To Town) fared better, although its earning potential may have been affected by the attack on Pearl Harbor, which occurred three days after the feature’s release. Neither film indicated that the Fleischers were ready to challenge powerhouse Walt Disney Studios at feature length animation.

It was as the Fleischers were in the midst of production on Mister Bug that Paramount approached the studio with a proposal for a series of cartoons based on the most popular comic book character of the day– Superman.

Superman, created by two aspiring comic book creators from Ohio, Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster, had debuted just a few years before in Action Comics #1 (June 1938). Siegel and Shuster created the character after being inspired by heroics of pulp characters like publisher Simon and Street’s Doc Savage, The Man Of Bronze. Their own Man Of Steel was an immediate runaway success and publisher National Periodicals (later DC Comics) launched a second title, the eponymous Superman, in the summer of 1939. However, two comic titles weren’t enough to slake the public’s appetite for the Man of Steel and a thrice-weekly radio series debuted on February 12, 1940 on the Mutual network.

Dave Fleischer was loathe to take on the series at first. He knew that the cartoons would be time consuming and would require more realistic animation and character designs than the studio had previously attempted. Such work would be labor intensive and expensive. Reportedly, Dave gave Paramount a rather inflated estimated per episode cost to produce the series, perhaps in an attempt to discourage them from pursuing the idea (Here, the number fluctuates somewhat. Leslie Cabarga’s book The Fleischer Story states Dave quoted Paramount $90,000.00 per episode, while Leonard Maltin’s Of Mice And Magic claims the figure was $100,000.00.).

But Paramount seemed willing to foot the bill, so Dave reluctantly agreed to go ahead with the cartoons. The first cartoon in the series, titled simply Superman, came in at a cost of approximately $50,000.00, three times the cost of a “Popeye” cartoon of comparable length. Subsequent entries in the series were budgeted at around $30,000.00 per short.

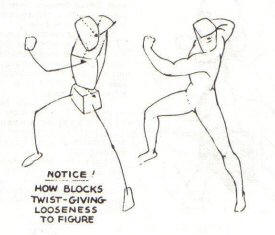

To bring the necessary realism to the cartoons’ look, Dave eschewed the traditional use of circles and ovals that formed the basis of all character design in favor of an approach that utilized blocks and wedges as the starting point. The animators also made use of pencil tests- filmed rough animation tests that allowed animators to judge how well the characters moved before their drawings were fully inked, colored and photographed. The cartoons also utilized the special effects department that had been created for the Gulliver’s Travels feature. The then-current Art Deco movement heavily influenced the cartoons’ designs and backgrounds. A subtle modification was made to the classic “S-shield” on Superman’s chest. Whereas the background of the emblem is yellow in the comics, the cartoons used a black background. This look was later used temporarily in the comics following the multi-part “Worlds At War” storyline in 2001.

The cartoons also used a more cinematic style to complement the increased realistic look of the animation. Characters moved through layers of shadow and light. Scenes were shot using multiple camera angles that required new backgrounds for each shot. Whereas traditional cartoons featured characters interacting on the same plane, the Superman cartoons had a greater sense of depth. The shorts are paced so that the edits accelerate the action towards the climax. Even the title cards, normally a static element in other cartoons’ opening segments, were dynamic and contained either extra animation or audio cues.

The cartoons also used a more cinematic style to complement the increased realistic look of the animation. Characters moved through layers of shadow and light. Scenes were shot using multiple camera angles that required new backgrounds for each shot. Whereas traditional cartoons featured characters interacting on the same plane, the Superman cartoons had a greater sense of depth. The shorts are paced so that the edits accelerate the action towards the climax. Even the title cards, normally a static element in other cartoons’ opening segments, were dynamic and contained either extra animation or audio cues.

However, for all their technical innovation, the Superman cartoons fell short in the story-telling department. A majority of the shorts fall into a rather predictable formula: some danger- usually a criminal gang, deranged scientist or natural disaster- makes its presence known, Lois investigates and becomes endangered herself, requiring Superman to rescue her while putting a stop to the initial threat. Beyond some basic broad strokes there is little characterization at all in the shorts. Lois is a spunky reporter and Clark is just hapless enough to seemingly fall for Lois’s efforts to ditch him on the way to their assignment.

While the characters lack strong definition, other elements may have been left intentionally vague at first, developing later over the series. For example, some fans have speculated as to what city the cartoons take place in. To the modern viewer, the idea that the cartoons are set in the fictional city Metropolis seems like a no-brainer. But like much in the Superman mythos, Metropolis didn’t exist in the beginning but was created as the comic grew in its early years. In Superman’s first appearance in the historic Action Comics #1, it is only mentioned the Clark Kent worked at “a great metropolitan newspaper.” In Action Comics #2, an out-of-the-country Clark Kent sends his story back to the Evening News of Cleveland, Ohio (Not so coincidentally, Cleveland was creators Siegel and Schuster’s home.). By December 1938 (and Action Comics #7), the newspaper is finally identified as the Daily Star, a “large metropolitan daily.” It wasn’t until the autumn of 1939 when Metropolis is finally named, in both Action Comics #16 (September 1939) and in the newly launched Superman #2 (cover dated Fall 1939). The Daily Star finally became the Daily Planet in the spring of 1940 when Action Comics #23 (April 1940) and Superman #4 (Spring 1940) hit the comics racks.

While the characters lack strong definition, other elements may have been left intentionally vague at first, developing later over the series. For example, some fans have speculated as to what city the cartoons take place in. To the modern viewer, the idea that the cartoons are set in the fictional city Metropolis seems like a no-brainer. But like much in the Superman mythos, Metropolis didn’t exist in the beginning but was created as the comic grew in its early years. In Superman’s first appearance in the historic Action Comics #1, it is only mentioned the Clark Kent worked at “a great metropolitan newspaper.” In Action Comics #2, an out-of-the-country Clark Kent sends his story back to the Evening News of Cleveland, Ohio (Not so coincidentally, Cleveland was creators Siegel and Schuster’s home.). By December 1938 (and Action Comics #7), the newspaper is finally identified as the Daily Star, a “large metropolitan daily.” It wasn’t until the autumn of 1939 when Metropolis is finally named, in both Action Comics #16 (September 1939) and in the newly launched Superman #2 (cover dated Fall 1939). The Daily Star finally became the Daily Planet in the spring of 1940 when Action Comics #23 (April 1940) and Superman #4 (Spring 1940) hit the comics racks.

The city featured in the cartoons is at first unnamed. The dense skyscraper-filled skyline suggests Manhattan; not surprising, as the Fleischer Studios were located in New York City until they moved to Florida in 1939. However, those familiar with the geography of Manhattan and its environs know that there are no dams (Arctic Giant) or surrounding mountain ranges for evil scientists (Mechanical Monsters) and criminals (The Bulleteers) to house their lairs.

Metropolis is finally named in the fifth cartoon of the series (The Bulleteers), when the Bulleteers make their first demands on the city. However, the seventh cartoon in the series, Electric Earthquake, clearly takes place in New York City. We can’t even excuse this by saying that Clark and Lois were on assignment in the Big Apple, as there are scenes set in the Daily Planet office with their editor. A few cartoons later in the series, Destruction, Inc. once again name the locale as Metropolis.

Speaking of the Daily Planet’s editor, it is interesting to note that with the exception of the first and second-to-last cartoon of the series, the Daily Planet’s editor is never named. At the time, Clark Kent had two bosses depending on which source you went with. In the comics he worked for editor George Taylor, while the radio series debuted Daily Planet editor Perry White in its second episode (February 14, 1940). Although called “Mr. White” by Clark in the first cartoon of the series, the Daily Planet’s editor goes unnamed for a majority of the series in order to avoid confusion between the two sources. Clark and Lois merely refer to their editor as “Chief”. It wasn’t until the series’ penultimate installment, The Underground World, when they would again refer to their editor as Perry White. This was done as the comics had finally come into line with the radio series.

The radio series influenced the cartoon series as well. Although there is little dialogue in each short, the Fleischers still needed to someone to voice Clark and Lois. They turned to Bud Collyer and Joan Alexander, the voice actors playing Clark and Lois on the radio series. Collyer continued his trick of lowering the register of his voice to distinguish Superman from his disguise of Clark Kent. For the voice of the Daily Planet editor/Perry White, radio announcer Jackson Beck was hired. After the run of cartoons ended, Beck would go on to take over the announcer spot and eventually the role of Perry White on the radio series. In addition to their main roles, Collyer and Beck would also contribute voices for several other characters who would appear in the various shorts.

In addition to the principal voice actors, the Superman cartoons also borrowed the phrases “Look! Up in the sky! It’s a bird. It’s a plane! It’s Superman!” and “Faster than a speeding bullet! More powerful than a locomotive! Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound!” from the radio series for each of the shorts’ opening segments.

The first cartoon in the series, released in September 1941, was met with critical and audience approval alike and the studio quickly set to work on producing more. However, shortly after the ninth cartoon in the series, Terror On The Midway, was released in July 1942, Paramount severed their connection with the Fleischers. Paramount had invested heavily in the animation studio, and felt that the meager profits being generated weren’t big enough to justify the expense.

Still Paramount needed cartoons to distribute, so it hired Fleischer writers Isidore Sperber and Seymour Kneitel and the Fleischer Studio business manager Sam Buchwald to head an in-house animation unit called Famous Studios. Under the Famous Studios moniker, both the Popeye and Superman series continued, with eight more animated installments for the Man of Steel.

Though they carried over the same stylized look and animation techniques, the Famous Studios Superman cartoons seem to lack a certain energetic spark compared the ones that Dave Fleischer had directed. Under Dave Fleischer’s direction, Superman routinely fought more science-fictional perils- giant robots, dinosaurs, and criminals with impossible weaponry. In the Superman cartoons produced under the Famous Studios banner, the Man of Steel often fought more mundane menaces like the gangsters in Showdown or got involved in wartime intrigues like the ones in Japoteurs, Eleventh Hour or Destruction, Inc.

Also, with the change from Fleischer to Famous Studios came a change to the cartoons’ opening. Instead of starting off with the iconic “Faster than a speeding bullet!” line, once the series was produced under the Famous aegis, the opening line was changed to “Faster than a bolt of lightening! More powerful than the pounding surf! Mightier than a roaring hurricane!”

The Superman cartoon series came to an end with Secret Agent, released on July 30, 1943, just under two years from its launch.

With the withdrawal of financial support from Paramount Studios, Fleischer Studios was forced to close its doors. Dave Fleischer moved over to Columbia Pictures to produce cartoons, though he only lasted there until 1944. He later worked for 15 years at Universal Pictures as a gag writer for their live action comedies.

Although it only lasted for 17 installments, the Superman cartoon series lives on in animation fans’ imaginations and has influenced other projects for decades. The series’ art deco design elements are still reflected today in the 1990s Batman and Superman animated television series and director Osamu Tezuka‘s manga Metropolis, which was adapted into an animated film in 2000 by Japanese director Rinatro. Director Kerry Koran‘s 2004 love letter to 1930’s and 40’s pulp adventure, Sky Captain And The World of Tomorrow, contained visual references to Mechanical Monster. There is no doubt that future films will reveal the unmistakable visual influence of Dave Fleischer’s timeless interpretation of the Man Of Steel.

Click here for the Fleischer Cartoons.

Continue on to the Famous Studios cartoons.

Special thanks to Bill Gatevackes for help in answering some of my more obscure questions on the early days of Superman comics.