Director Quentin Tarantino has never hid his love for 1970s exploitation genre films. His occasional film festivals held in Austin, Texas in conjunction with the Austin Film Society have often featured forgotten and nearly-forgotten grindhouse fare such as Billy Jack (1971) and Framed (1975) with Joe Don Baker. His Rolling Thunder distribution company (named after the 1977 revenge flick) has brought back into circulation b-movies such as 1975’s Switchblade Sisters (from blaxploitation director Jack Hill) and the 1993 Japanese gangster film Sonatine featuring Takeshi “Beat” Kitano. But with his new film Kill Bill, Volume 1 (Volume 2 will follow in late February) Tarantino has taken all of his grindhouse inspirations, filtered them through his own particular vision and created a masterpiece that is more than the sum of his influences.

Director Quentin Tarantino has never hid his love for 1970s exploitation genre films. His occasional film festivals held in Austin, Texas in conjunction with the Austin Film Society have often featured forgotten and nearly-forgotten grindhouse fare such as Billy Jack (1971) and Framed (1975) with Joe Don Baker. His Rolling Thunder distribution company (named after the 1977 revenge flick) has brought back into circulation b-movies such as 1975’s Switchblade Sisters (from blaxploitation director Jack Hill) and the 1993 Japanese gangster film Sonatine featuring Takeshi “Beat” Kitano. But with his new film Kill Bill, Volume 1 (Volume 2 will follow in late February) Tarantino has taken all of his grindhouse inspirations, filtered them through his own particular vision and created a masterpiece that is more than the sum of his influences.

Uma Thurman is The Bride, a member of the elite Deadly Viper Assassination Squad. When the Bride decides to leave the group to settle down and marry, the other members of the team show up at the wedding, killing everyone present and putting The Bride in a four year coma. Understandably enraged at having had four years of her life, her planned future and her unborn baby all taken from her, The Bride sets out to extract her revenge on her former team mates (Vivica A. Fox, Lucy Liu, Darryl Hannah and Michael Madsen) and their leader, the enigmatic Bill (David Carradine). Volume 1, sees the Bride start out on her quest and her encounters with a now turned suburban housewife Fox and Tokyo organized crime head Liu before ending on an emotional cliffhanger leading to the next year’s concluding installment.

Even with Tarantino’s trademark non-linear storytelling, the plot is strictly fairly linear, in much of the style of the many of the kung fu auctioneers released by the Hong Kong based Shaw Brothers Studio from the ‘60s to the early ‘80s. Tarantino is plundering much of the same source material that Ang Lee did for 2000’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. But where Lee concentrated on themes of love, honor and duty, Tarantino is more concerned with vengeance, a much rawer and bloodier business.

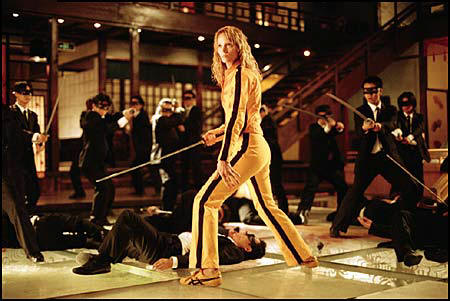

Make no mistake, Kill Bill is a violent picture and that may put some audience members off. But the violence almost transcends itself at points. Tarantino (along with fight choreographer Yuen Wo-Ping) stage the most violent and lengthy segment (“The Showdown at the House of Blue Leaves”) almost as if it was a dance number, with long flowing shots that showcase the fighting skill of all involved. At one point Thurman and several opponents square off in silhouette backlit by blue light recalling An American In Paris.

Make no mistake, Kill Bill is a violent picture and that may put some audience members off. But the violence almost transcends itself at points. Tarantino (along with fight choreographer Yuen Wo-Ping) stage the most violent and lengthy segment (“The Showdown at the House of Blue Leaves”) almost as if it was a dance number, with long flowing shots that showcase the fighting skill of all involved. At one point Thurman and several opponents square off in silhouette backlit by blue light recalling An American In Paris.

Kill Bill wears its inspirations on its sleeve. It opens with the title card “Filmed in Shaw-Scope” that graced the opening seconds of many a Shaw Brothers picture. The flashback describing fellow assassin O-Ren’s background is done in Japanese animation style. Sonny Chiba, start of the Streetfighter series of films in the `70s, appears as a master forger of samurai swords. Former Shaw Brothers star Gordon Liu (1978‘s 36th Chamber of Shaolin) is the head of Lucy Liu’s army of black-suited, domino-masked army of sword-wielding thugs.

While many may pick up on the Bride’s yellow track suit as a tip of the hat towards Bruce Lee’s Game Of Death (1978), many may not get the finale to the House of Blue Leaves fight as being visually inspired by the Shaw Brothers production Lady Snowblood (1973). Still, one doesn’t need to know that Darryl Hannah’s character is a riff on the movie Thriller (AKA They Call Me One-Eye, 1974) to enjoy Kill Bill any more than a filmgoer in 1977 needed to know that Star Wars was George Lucas’ attempt to filter the Flash Gordon serials of the `40s through the writings of Joseph Campbell.

This same philosophy seems to have directed Tarantino’s choice of music for the film’s soundtrack. Here he’s utilized tracks ranging from Al Hirt’s “Green Hornet” (from the 1966 television series) to Isaac Hayes’ “Run Fay Run” (from Three Tough Guys, 1974) and the main title theme from Truck Turner (1974) to Bernard Herrman’s theme from Twisted Nerve (1968). This is not the first time that he’s cannibalized another film’s soundtrack. Jackie Brown (1997) opened with the theme from Across 110th Street from the 1972 crime drama of the same name. Tarantino makes the most of these selections, cutting images to the music’s rhythm for maximum impact.

But Kill Bill isn’t just a triumph of style, there’s plenty of substance also. These characters know they are part of a cycle of violence that they may not be able to break free from. Early in the film the Bride regrets that Fox’s four-year old daughter discovers the end result of their confrontation and tells her “If when you grow up, if you’re still raw about it, I’ll be waiting.” When The Bride defeats Lucy Liu’s O-Ren, there is not a sense of accomplishment, but one of remorse, knowing that O-Ren’s life was forged from a similar experience of violent loss that has set the Bride on her own path of retribution. Whether or not the Bride can break free of this cycle of violence, especially in light of the film’s final line of dialogue, will have to remain until February’s Volume 2 to be seen.

But Kill Bill isn’t just a triumph of style, there’s plenty of substance also. These characters know they are part of a cycle of violence that they may not be able to break free from. Early in the film the Bride regrets that Fox’s four-year old daughter discovers the end result of their confrontation and tells her “If when you grow up, if you’re still raw about it, I’ll be waiting.” When The Bride defeats Lucy Liu’s O-Ren, there is not a sense of accomplishment, but one of remorse, knowing that O-Ren’s life was forged from a similar experience of violent loss that has set the Bride on her own path of retribution. Whether or not the Bride can break free of this cycle of violence, especially in light of the film’s final line of dialogue, will have to remain until February’s Volume 2 to be seen.