Disney Closes Florida Animation Studio

An In Depth Look At What Is Viewed As

The End Of Traditional Animation at Walt Disney Studios

By Rich Drees

In a move that had long been expected, Walt Disney Studios closed its Orlando, Florida based animation studio on Monday, January 12, 2004, putting approximately 250 animators, technicians and other personnel out of work. This is following the late November 2003 cancellation of the feature A Few Good Ghosts, which was being developed by the studio, the closure of Disney Feature Animation’s studios in Paris and Tokyo as well as layoffs and salary cuts at the Orlando studio last year.

|

|

Lilo & Stitch, one of the hit films produced at Disney Feature Animation's Florida based studio. |

While the closure was expected, it still came as a blow to the many artists who worked there. The studio was responsible for Mulan (1998), Lilo & Stitch (2002) and Brother Bear (2003), all traditionally hand drawn animated films. With the cancellation of A Few Good Ghosts, Disney currently has no hand drawn animated films scheduled beyond the upcoming release of the already completed Home On The Range in April 2004.

Instead the studio plans on concentrating on producing films using three-dimensional computer generated animation. Although the studio has had hits with the computer animated films Toy Story (1995), A Bug’s Life (1998), Monsters, Inc. (2001) and Finding Nemo (2003), these films were produced by the independent studio Pixar Animation Studios, with Disney only distributing them. Disney’s deal with Pixar is set to expire at the end of 2004 and as of this writing has not yet been renewed.

In a statement, David Stainton, president of Walt Disney Feature Animation, said, “This difficult decision was based on what is best strategically for our business in both the short and long term. Having the entire animation group working together in Burbank under one roof will further enhance our filmmaking process."

Disney publicists have insisted that some animators from the Orlando studio will be offered jobs at the Burbank facilities, though some reports have alleged that only two to 20 jobs will be transferred.

Many Disney observers feel that the studio has already let go some of their best animators in the last few rounds of cut backs. Recently, when the engineers who plan the Disney park attractions, the Walt Disney Imagineering division, approached the Feature Animation division to supply new animation as part of their refurbishment of Disneyland’s Tommorowland’s “ExtraTERRORestrial Alien Encounter” attraction into an attraction called “Stitch’s Great Escape.” However, since the Feature Animation division had let go many of the animators who had worked on Lilo & Stitch, the film on which the ride is based, they were unable to produce footage replicating that film’s distinctive style. The Imagineering division was forced to contract the work out to the independent studio Renegade Animation.

|

|

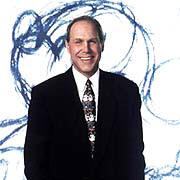

Roy O. Disney |

This is the second public relations black eye that Disney has suffered in the past few months. On November 30, Roy O. Disney, whose father co-founded the studio with his uncle Walt, publicly resigned as Vice-President in charge of feature animation, claiming in part that company chairman’s Michael Eisner’s focus on short term profits is a far cry from the ideals that Walt Disney started the company with. Speaking at a convention of members of the NFFC-The Club For Disneyana Enthusiasts, on January 17, 2004 Disney stated that the Disney name “Stands for quality. It stands for families, it stands for getting your money's worth and it stands for a lot of innovation and a lot of new and creative ideas that make things fun every time you visit a park or go to a film."

In a statement issued the day after the official closing announcement had been made, Disney issued a statement calling the move “another example of Michael Eisner's de-emphasis of creativity and total indifference to the impact his decisions have on the people who helped to make the company great." At the NFFC Convention, Disney further elaborated, stating, “To me, it's a failure of management to figure out what to do with creative people, a failure to realize creativity is the basis of this company."

The Florida unit was first established in 1989 with approximately 40 employees. As part of the Disney-MGM Studios complex of theme parks, park visitors were able to take a tour of the studio and actually observe the animators at work. In 1998, the unit moved into a new $70 million faculty. At the studio’s height in the mid-1990s, it employed approximately 400 artists and technicians.

Among the projects completed by the studio include the musical segment “I Can’t Wait To Be King” for The Lion King, the feature films Mulan, Lilo And Stitch and Brother Bear, the three Roger Rabbit short features Tummy Trouble (1989), Rollercoaster Rabbit (1990) and Trail Mix-Up (1993) and the short John Henry (2000).

Disney’s more recently produced traditionally animated films have not fared as well at the box office as their animated features did just a decade or so earlier. The recently released Brother Bear has only grossed approximately $83.7 million dollars during its first 12 weeks of release. The film cost an estimated $90 to $100 million dollars to produce. Conversely, The Lion King, which was released in June 1994, pulled in an estimated $312.8 million in box office receipts against a production cost of approximately $45 million dollars.

|

|

Did Atlantis: The Lost Empire not find its audience due to studio executive interference? |

Many theories have been advanced for the decline in box office revenue of Disney films. Some claim that there’s a decline in the quality of the films and point blame to numerous suggestions from various company executives who may or may not have a creative background. It was reported that an executive had request the removal of a segment featuring attacking monsters from Atlantis: The Lost Empire (2001). This allegedly confused the animators, who felt that the action sequence would appeal to the pre-teen boys to whom the movie was being marketed. Atlantis would only do $84 million in box office receipts.

Some analysts think that the recent explosion in the popularity of the DVD home video format has inadvertently cut into theatre attendance with potential audiences deciding to wait and “catch it on video” instead of seeing a film in the theatre.

It is possible that Disney became a victim of its own success. When the films like The Lion King, Beauty And The Beast (1991) and Aladdin (1992) were big hits not only at the box office but also on home video, executives wanted for more hits. Where Disney would previously only release one major film a year, they were pushing to get two and three major releases a year.

In addition, the studio also released numerous cheaply produced direct-to-video sequels, produced by the company’s television animation division. Whereas company founder Walt Disney was against producing sequels to the studio’s animated classics, such derivative products have now become part of their overall business strategy. Many Disney fans, and reportedly some insiders, are of the opinion that the company has over-saturated the market, diluting the “specialness” of a theatrical Disney film.

|

|

Michael Eisner |

In an address to the 14th Annual Smith Barney Citigroup Entertainment, Media and Telecommunications Conference on January 6, 2004 in Phoenix, Arizona, Disney chairman Michael Eisner stated, “Perhaps our most stellar long-term example of producing cost-effective entertainment is our TV Animation business. This unit is committed to extending the life of Disney animated franchises by producing direct-to-video sequels and TV series, utilizing less expensive development and production techniques. We have produced a total of 15 animated direct-to-video sequels since 1994. With healthy double-digit returns that sometimes rise to triple digit, these films are expected to contribute profits of more than $1 billion over their lifetime. This enormous value creation does not take into account the fact that the life of these assets are extended in the hearts and minds of consumers, allowing our characters to have continuing merchandise appeal.”

Eisner used by way of example the success of the Orlando studio produced hit Lilo And Stitch, which had grossed $263 million in worldwide box office receipts before selling over 18 million video units. “Within a year of the movie, our TV Animation unit released into home video Stitch: The Movie, which is on track to sell more than five million units worldwide. Then came the Lilo & Stitch hit TV series on the Disney Channel. Another Lilo & Stitch sequel is currently in the works. In essence, we have created a great character franchise in Lilo & Stitch that will flourish across our company and across the globe for years to come.”

No mention was made in his remarks to the closing of the studio that had produced such an asset to the company.

While Disney as a company seems interested in getting out of the traditional animation business, many of it’s now-former employees are not. Several animators who were let go during an earlier round of layoffs at Disney’s Orlando studio joined together to form Legacy Animation Studios.

“We believe that traditionally animated films are still a viable form of entertainment,” states Legacy Animation Studios Directing Manager, Eddie Pittman in a company press release. “Our goal is to create quality animated films with compelling stories and strong characters and to continue Walt Disney’s legacy of hand drawn animation.”

The studio currently consists of 15 animators whose work experience dates back 25 years and spans over 25 Disney and non-Disney animated productions. Legacy currently has three projects in development including a short film that will begin production in late January 2004.

This is not the first time that animators have left Disney to strike out on their own. In September 1979, animator Don Bluth left Disney to form his own studio, taking several animators with him. Bluth’s studio achieved success with their first film, 1982’s The Secret of NIMH, as well as launching the An American Tail (1986) and The Land Before Time (1988) franchises.