In Remembrance: Frank Thomas

Frank Thomas, a member of the group of Walt Disney Studio animators whom

Walt Disney had nicknamed “The Nine Old Men,” has passed away on Wednesday,

September 8, 2004 at his home in La Canada Flintridge, California. He was

92.

Frank Thomas, a member of the group of Walt Disney Studio animators whom

Walt Disney had nicknamed “The Nine Old Men,” has passed away on Wednesday,

September 8, 2004 at his home in La Canada Flintridge, California. He was

92.

Born on September 5, 1912 in Santa Monica California, Thomas’ father was an educator who had served as a high school principal in Santa Monica, then later Sacramento before becoming president of Fresno State College. He first became interested in drawing at a young age when he saw his older brother Craig doing it. By the time he was in high school, he was drawing comics for his school newspaper and yearbook.

Thomas attended Fresno State College for two years, where he concentrated on music, theatre and drawing courses. His sophomore year, he was elected class vice-president. But in charge of furnishing entertainment for class meetings, Thomas suggested that the class make a short comedy film. The result was The Soph Movie, a 31 minute short feature for which Thomas was co-screenwriter, producer, director, editor and lead actor. Thomas would credit much of his knowledge of creating and staging successful gags on his experience making the film. The Soph Film was a success and was shown up and down the California coast, earning the class $1,000.00 over the cost of its production.

His junior year of college, Thomas transferred to Stanford University. There he studies art, frequently contributing comics to the school’s humor magazine, The Chaparral. It was there that he also met his life long friend Oliver “Ollie” Johnson, who would work with him at the Disney Studio. Following graduation he attended Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles. Upon seeing the Disney Silly Symphony cartoon The Flying Mouse (1934), Thomas became interested in a career in animation. In John Canemaker’s 2001 book Walt Disney’s Nine Old Men, Thomas stated that this particular cartoon stood out from other animated shorts because “this one had more pathos and feeling for the characters and more acting. And it really grabbed me. It wasn’t a series of gags. I thought, ‘Gee, this Flying Mouse, if they’re going in that direction, there might be something there that would interest me.’” After submitting his portfolio, he was hired and began work at the end of September 1934,

Thomas worked in the in-between department, animating character movement as designated by a cartoon’s lead animator, for six months. During that time he was able to help get his friend Johnston hired. Thomas was then promoted to assist animator Fred Moore, who had done work on The Flying Mouse, which had so impressed Thomas. After almost a year, Thomas was promoted to the level of junior animator based on a pencil test animation he did. His first solo animation assignment was in the 1936 short Mickey’s Circus where several seals swarm of a hapless Donald Duck. He followed up with a sequence in Mickey’s Elephant (1936), but it was a scene for the short Little Hiawatha (1937), in which the child Hiawatha has a nose-to-nose confrontation with a bear cub that caught studio head Walt Disney’s eye and had him transferred over to work on the feature length project Snow White And The Seven Dwarves (1937), much to some more senior animators jealousy.

On Snow White Thomas truly shone with his ability to convey character and emotion. Assigned to animate key sequences involving the seven dwarves, he brought a hitherto unseen emotional depth to the scene of the Dwarves grieving over Snow White’s presumably dead body.

It was on Snow White that Thomas and the other eight animators who Walt Disney would refer to as his “nine old men,” in a joking reference to President Roosevelt’s complaint about the Supreme Court being “nine old men all too aged to recognize a new idea,” would first work on the same feature film. Ironically, Disney’s Nine Old Men where all instrumental in helping realize Disney’s dream to refine various animation techniques and bring a new sense of realism to his cartoons.

|

|

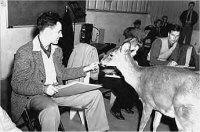

Thomas gets to know a real deer while doing preliminary work for 1942's Bambi. |

Thomas contributed several memorable sequences to each of the Disney animated feature films he worked on. For Pinocchio (1940) he animated both the frightened Pinocchio after he had been kidnapped by the villainous puppeteer Stromboli and the energetic dance the wooden boy does while singing “I’ve Got No Strings.” For 1942‘s Bambi Thomas managed to salvage the sequence of Bambi learning to ice skate after showing Disney a test reel of how the sequence could work after the studio head had decided to abandon it. In 1949’s The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, he worked on a sequence showing Ichabod Crane’s descent into terror while riding through a wood supposedly haunted by the Headless Horseman.

Thomas also worked on a number of classic animated shorts early in his career including The Brave Little Tailor (1938), The Pointer (1939) and The Practical Pig (1939). During World War II, he worked on the several Disney produced homefront propaganda and training films including Education For Death (1943) and The Winged Scourage (1943).

His first job animating a villain was on Cinderella (1950) where Thomas brought to life the cruel Stepmother. Disney liked his work so much that Thomas was assigned to animate the villainous Queen of Hearts in Alice In Wonderland (1951) and Captain Hook in Peter Pan (1953). For Lady And The Tramp (1955), he animated the romantic first date between the two dogs that culminates in an accidental kiss while eating a strand of spaghetti. In order to bring a uniqueness to the three fairies in Sleeping Beauty (1959), Thomas spent time studying old women at the grocery store.

|

|

A still from a Thomas animated sequence in the 1938 Mickey Mouse short The Brave Little Tailor. |

Thomas also animated sequences for The Sword And The Stone (1963), the dance Dick Van Dyke shared with several animated penguins in Mary Poppins (1964), The Jungle Book (1967), The Aristocats (1970), Robin Hood (1973), The Rescuers (1977) and The Many Adventures of Winnie The Pooh (1977). He last worked on 1981’s The Fox And The Hound before retiring.

With long time friend Johnston, Thomas collaborated on the 1981 book Disney Animation: The Illusion Of Life, considered by many to be the definitive text on the development of Disney animation techniques. The duo collaborated on three more books- Too Funny For Words (1987), Walt Disney’s Bambi: The Story And The Film (1991) and The Disney Villain (1993). They were also featured in the 1991 documentary Frank and Ollie.