“I don’t see them. I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema. Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”–Martin Scorsese on Marvel films, told to Empire Magazine.

Being that I am the Comic Book Editor Emeritus of this site, you might be expecting me to write an anger-filled diatribe in response to that quote, listing all the ways Marvel movies in particular and comic book movies in general are “cinema.” I’m not going to do that. Well, not exclusively.

No, I will be speaking about a point raised by Scorsese in that quote. It is the system where a snobbish Hollywood separates its good films from its bad. The deciding factor is not critical reviews, nor is it popularity with an audience. No, for most of Hollywood, the populist blockbuster is bad, and the artistically pure “cinema” is good.

This philosophy predates the rise of the comic book movie by decades. There has been a bias against genre films and summer blockbusters since the 1970’s. Not matter how well made your comedy, science-fiction, or horror film might be, no matter how well written, how emotionally resonant it is, it can never hold a candle to the films that Scorsese says is “the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.” The films that handle “important” themes and subject matter.

Scorsese doubled down on his stance at a press conference for The Irishman at the London Film Festival, a stance that echos one that his Taxi Driver star Jodie Foster made in 2017:

Scorsese doubled down on his stance at a press conference for The Irishman at the London Film Festival, a stance that echos one that his Taxi Driver star Jodie Foster made in 2017:

Going to the movies has become like a theme park. Studios making bad content in order to appeal to the masses and shareholders is like fracking – you get the best return right now but you wreck the earth. It’s ruining the viewing habits of the American population and then ultimately the rest of the world. I don’t want to make $200m movies about superheroes.

This, of course, is bullshit. It has always been bullshit and always will be bullshit. But it is bullshit that has been spread so far and so thick that filmmakers and some fans consider it the gospel.

The problem started in the late-1960s when New Hollywood took over. A group of iconoclast like Scorsese hit the scene, trained at film schools on the works of Fellini, Truffaut, Bergman and Kurosawa, decided to apply what they learned to films, changing the cinematic landscape forever. Flirty romances like Pillow Talk and Adam’s Rib fell out of favor, replaced nihilistic and ultimately doomed romances of Bonnie and Clyde and Harold and Maude. The wide-open, colorful westerns like Rio Bravo made way for blood-soaked oaters like The Wild Bunch or acerbic fare such as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. And whimsical musicals like My Fair Lady took a back seat to the sultry and dark Cabaret.

New Hollywood held power for about a decade with their new way of doing things, ruling at the box office, at Oscar time, and with the critics. But then George Lucas and Steven Spielberg came along.

Lucas and Spielberg were also students of Kurosawa and Truffaut, but instead of apply their knowledge to New York street hustlers and sprawling Mafia epics, they worked in less respectable genres such as science-fiction and horror. The blockbuster, bane of the cinema, was born with Jaws and came of age with Star Wars. Studios, realizing they could make more money with one Star Wars than you could with five Midnight Cowboy‘s, leaned into the blockbuster and New Hollywood’s brand of “cinema” lost its dominance at the box office.

Lucas and Spielberg were also students of Kurosawa and Truffaut, but instead of apply their knowledge to New York street hustlers and sprawling Mafia epics, they worked in less respectable genres such as science-fiction and horror. The blockbuster, bane of the cinema, was born with Jaws and came of age with Star Wars. Studios, realizing they could make more money with one Star Wars than you could with five Midnight Cowboy‘s, leaned into the blockbuster and New Hollywood’s brand of “cinema” lost its dominance at the box office.

Certainly a lot of Scorsese’s and his cohorts’ disdain and dismissal of the blockbuster and genre films comes from having to fight for the moviegoer’s money with them. Scorsese admitted as much at the weekend press conference I mentioned above. However, there was one field of battle where serious cinema still reigns–the Oscars.

The Academy Award for Best Picture seldom recognizes the best pictures in the land. Maybe once of it did, but over the years it has become a joke, a collection of tropes that the Academy wants you to believe represents the best in cinema.

Is your film a drama? Is it taken from the annals of history or is it biographical in nature? Does the main character have some kind of disability? Deadly disease? Do they fight against prejudice? A corrupt system? Bigotry? Does the film have some kind of technical hook like being silent or a musical that sets it apart from the rest? Is it done by creators that have been nominated before? If your films meet two or more of those criteria, then your film might be an Oscar nominee!

Is your film a drama? Is it taken from the annals of history or is it biographical in nature? Does the main character have some kind of disability? Deadly disease? Do they fight against prejudice? A corrupt system? Bigotry? Does the film have some kind of technical hook like being silent or a musical that sets it apart from the rest? Is it done by creators that have been nominated before? If your films meet two or more of those criteria, then your film might be an Oscar nominee!

However, if you are a genre film, a blockbuster or, god forbid, a comedy, you can feel safe in making other plans for Oscar night. Yes, there have been genre films that have won Oscars (Shape of Water most recently), blockbusters that took home the award (most memorably, Titanic) and even comedies have won a Best Picture statue, but you’d have to go all the way back to 1977 and Annie Hall to find the last pure comedy to win one. But most years, these types of films are lucky just to get nominated and the nomination amounts to basically throwing the film a bone.

It wouldn’t be bad if the popular films were snubbed for, well, good movies. Let’s take a look at the Best Picture nominees from last year. The 8 films had an average score at Rotten Tomatoes of 85% Fresh. That’s a solid B average for a group of films that claim to be the best the year has to offer. The curve was brought down by two nominees that barely met Rotten Tomatoes’ qualifications for being a good film–Vice (66% Fresh) and Bohemian Rhapsody (61% Fresh). The film that won the Oscar? Green Book? That was 78% Fresh, way below the average. What film was best reviewed out of the nominees? That big old theme park superhero movie Black Panther at 97% Fresh.

Obviously, the nominees weren’t the best reviewed films of the year, and it wasn’t even close. The only film that would have made the cut was Black Panther. If you took a look at the best reviewed films of 2018, counting only films that had 200 or more reviews and discounting any documentaries, foreign films and animated movies (all of which would have had their own category), the best picture race would have looked a whole lot different. Small films that flew under the radar such as Leave No Trace (100% Fresh), buzzworthy indie films like Eighth Grade (99% Fresh), The Hate U Give (97% Fresh), and The Death of Stalin (96% Fresh), and, yes, popular or genre fare like Mission Impossible: Fallout (97% Fresh), Can You Ever Forgive Me? (98% Fresh) and Paddington 2 (100% Fresh) would have gotten a nomination.

I can almost hear some of you out there. “Paddington 2? Are you serious? You want a talking bear movie to be nominated for an Oscar? Get real!” If you are are thinking that, then, sir or madam, you are part of the problem. Paddington 2 set records when it was reviewed by 235 critics who all liked it. That is almost impossible that that many cynics could come to an agreement about the high quality of the film. Why should a finely crafted, engaging and entertaining film be slighted because it is a family-friendly film instead of a turgid, cliched drama? The category is “Best Picture” not “Best Picture Based On A Limited Number Of Topics That A Small Group Of Auteurs Feel Are Important.” Maybe if Paddingtion was struggling to save the family farm while battling AIDS his film might have gotten more respect. The only reason why Paddington 2 should not have gotten nominated for this year’s awards is the fact that technically it came out in limited release in 2017, and should have been nominated for the 2018 program.

I can almost hear some of you out there. “Paddington 2? Are you serious? You want a talking bear movie to be nominated for an Oscar? Get real!” If you are are thinking that, then, sir or madam, you are part of the problem. Paddington 2 set records when it was reviewed by 235 critics who all liked it. That is almost impossible that that many cynics could come to an agreement about the high quality of the film. Why should a finely crafted, engaging and entertaining film be slighted because it is a family-friendly film instead of a turgid, cliched drama? The category is “Best Picture” not “Best Picture Based On A Limited Number Of Topics That A Small Group Of Auteurs Feel Are Important.” Maybe if Paddingtion was struggling to save the family farm while battling AIDS his film might have gotten more respect. The only reason why Paddington 2 should not have gotten nominated for this year’s awards is the fact that technically it came out in limited release in 2017, and should have been nominated for the 2018 program.

But this experiment goes to show that even the Academy considers “cinematic” fare to be more about prestige than actual quality. Leave No Trace, Eighth Grade and The Hate u Give all have the characteristics of what Scorsese would consider “cinema.” None were nominated. It’s a case of reverse snobbishness. Those films might be better examples of “cinema, ‘ but their profiles was much lower than the inferior films that garnered a nomination.

Only twice since 2000 has the best reviewed film also won the Best Picture Oscar–2012 with Argo and 2016 with Moonlight. Nine times the best reviewed film wasn’t even nominated for Best Picture (with a caveat: that many of the snubs happened before the Academy expanded to up to 10 nominees in 2009, and many of the films snubbed were animated fare, many of which were nominated, if not won, the Best Animated Feature Award the year they were eligible.). Most egregious was 2011, where Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2 was the best reviewed film of the year yet didn’t get a Best Picture nod, yet the critically lambasted Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (46% Fresh, the lowest Tomatometer score of any Best Picture nominee) was nominated. Adding insult to injury, only nine films were nominated that year. Which means the Academy could have thrown a bone to the final film of the Harry Potter franchise and still make the worst mistake in Oscar history.

Only twice since 2000 has the best reviewed film also won the Best Picture Oscar–2012 with Argo and 2016 with Moonlight. Nine times the best reviewed film wasn’t even nominated for Best Picture (with a caveat: that many of the snubs happened before the Academy expanded to up to 10 nominees in 2009, and many of the films snubbed were animated fare, many of which were nominated, if not won, the Best Animated Feature Award the year they were eligible.). Most egregious was 2011, where Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2 was the best reviewed film of the year yet didn’t get a Best Picture nod, yet the critically lambasted Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (46% Fresh, the lowest Tomatometer score of any Best Picture nominee) was nominated. Adding insult to injury, only nine films were nominated that year. Which means the Academy could have thrown a bone to the final film of the Harry Potter franchise and still make the worst mistake in Oscar history.

However, falling rating for the Oscar telecast showed the Academy the error of their ways. Last year, changes were proposed to the nomination process to increase viewership. Were they going to wrestle the nomination process away from the cinemaphiles so great films could be nominated regardless of genre or popularity? Not exactly.

Their solution was to introduce a “Best Popular Film” category. This is a familiar remedy the Academy employs in order to preserve the sanctity of Best Picture. How many times have you left an animated feature, a foreign film or a documentary and thought you had just seen the best picture of the years? It has to have happened at least once. But you seldom see these types of films nominated for the big award because they are shunted to their own awards for the telecasts. Occasionally, you’ll see a animated or foreign feature nominated for Best Picture, but never more than one per year and they will never win the award.

But the Academy thought this was the most elegant of elegant solutions. This way, fans would tune in to root their favorite films while being exposed to the far superior cinematic fare that gets nominated for Best Picture. Of course, we never found out how this new category was supposed to work, because fans rose up in unison and loudly proclaimed what a crappy idea it was. Because unlike what the Academy and A-listers like Scorsese and Foster think, fans aren’t poisoned to think blockbusters are good and cinematic fair is bad. They know good movies are good movies and if the Academy truly wanted to recognize the best in popular film, they can do so in the Best Picture category.

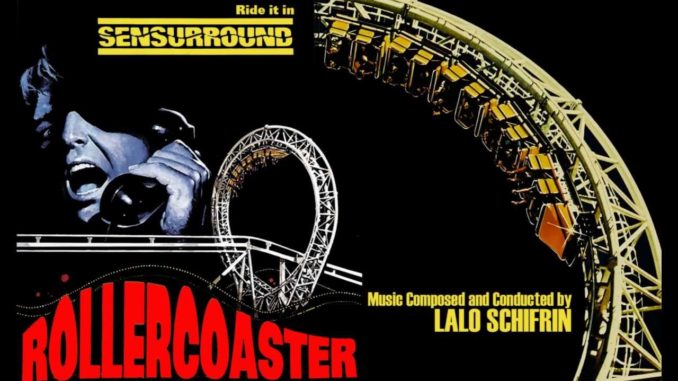

Then there is the whole “theme park” insult. I don’t know about you, but I think theme parks are fun. By referring to “theme park” films so dismissively, Scorsese and Foster are saying the only valid form of cinematic expression are films that leave their viewers feeling worse going out than going in. Films that make you sad, depressed or angry are far superior to films that scare you, leave you laughing or stimulate your sense of wonder. However, with films as in life, being morbidly serious doesn’t make you deeper, more interesting, or more entertaining. And you don’t have to be so serious to be a great film.

Then there is the whole “theme park” insult. I don’t know about you, but I think theme parks are fun. By referring to “theme park” films so dismissively, Scorsese and Foster are saying the only valid form of cinematic expression are films that leave their viewers feeling worse going out than going in. Films that make you sad, depressed or angry are far superior to films that scare you, leave you laughing or stimulate your sense of wonder. However, with films as in life, being morbidly serious doesn’t make you deeper, more interesting, or more entertaining. And you don’t have to be so serious to be a great film.

That’s the whole point. You can have films made that show human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being in films of any genre or popularity. You can have finely crafted, excellently written, and brilliantly acted work in any film, not just in the “cinematic fare” that snobs like Scorsese and Foster believe are the best. You can have stinkers in both too, but to believe one genre or type of film making is superior to all others exclusively because of its content is completely and utterly wrong. Scorsese’s and Foster’s condemnation of “theme park” films is an exercise of enormous egos. They don’t like them, so they think they are bad and we are all stupid if we think otherwise. I’d prefer to think that good movies are good movies and feel empowered to enjoy film whether they feature thunder gods going through PSTD or the life story of a gangster making a break from his life a crime. Because that is the way films should be.

[…] if even the very act of making a distinction between popular culture and elite culture is not equivalent to snobbery. Furthermore, what was once known as "high" culture has lost its former prestige: pop […]